The 45th president of the United States lied about everything, even the weather.

It started his first week in office. Beneath a dishwater-gray sky in January 2017, President Donald Trump delivered the first lines of his inaugural address outside the Capitol building. Attendees huddled under ponchos and umbrellas as it began to rain, and the drops continued to fall until near the end of the speech.

The way Trump told the story, the sky opened up and the sun shone down on him, bathing him in its light. “The truth is,” he said the next day, that the rain “stopped immediately. It was amazing. And then it became really sunny. And then I walked off, and it poured right after I left. It poured.” (The sun, in fact, had never appeared that dreary day in Washington, D.C.)

The outgoing president is known as a font of falsehoods. According to the most recent tally from the fatigued fact-checkers at the Washington Post, he lied more than 30,000 times over the course of his term. The falsehoods were sometimes about small things, like the size of the crowd at his inauguration, and often about crucial events and basic facts, like the coronavirus pandemic and the result of the presidential election he lost. But his fibs about the weather are possibly the weirdest. One of the many unsettling aspects of the past four years is that many believed them. If Americans can no longer agree on whether it’s raining or sunny — the stuff of small talk — then what’s left?

Alex Wong / Getty Images

Trump has done more than straight-up lie about the state of the sky. He honed a special talent for making political language slippery, introducing confusion where there was once shared understanding. Last September, he called himself the “No. 1 environmental president since Teddy Roosevelt.” That isn’t just a head-scratching boast; it undermines the word “environmental.” A word untethered to reality starts to lose its meaning. Trump, after all, pulled the United States out of the Paris Agreement and worked to prop up the fossil fuel industry; if that’s what an environmentalist does, then environmentalists are … anti-environment.

And what to make of an “Environmental Protection Agency” that doesn’t protect the environment? Despite Trump’s oft-repeated vision of America having “the cleanest water, the cleanest air,” his administration actively undermined that possibility. Left unchecked, the EPA’s full plans to dismantle clean air and water protections would have led to a conservative estimate of 80,000 premature deaths per decade, according to one Harvard study from 2018.

If you’ve read 1984, the George Orwell classic that explores a dystopian society where a totalitarian regime crushes critical thinking, then the idea that an agency could carry out the opposite of its mission might sound familiar. “The Ministry of Peace concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Truth with lies, the Ministry of Love with torture, and the Ministry of Plenty with starvation,” the book explains. Originally published in 1949, the book quickly rose to the top of Amazon’s bestseller list after Trump won the 2016 election. Orwell coined “doublethink” — a form of brainwashing that encourages people to simultaneously hold two beliefs that contradict each other — way before Kellyanne Conway, Trump’s former senior counselor, came up with “alternative facts.”

“There have definitely been times in which I felt like I’m reading doublespeak,” said Gretchen Gehrke, who has been tracking the changing language on government websites over the past four years, and once worked as a scientist at the EPA.

The Trump administration purged whole pages about climate change from government websites. New phrases were born as government employees sought new ways to talk about the overheating planet without saying “climate change.” You heard officials use oblique phrases like “rising natural hazard risk,” “pre-disaster mitigation,” and “weather extremes.” They replaced concrete terms with words calibrated to sound nice (“resilience,” “sustainability”), which tended to obscure environmental problems rather than address them directly.

“Everything is about resilience now,” Gehrke said. “I think a lot of that is because you don’t have to talk about what the problem is to say you need to be ‘resilient,’ or to ‘adapt to a changing future.’” That ambiguity allowed the government to avoid the polarized term and continue to address the needs of its Republican voters, like farmers struggling to adapt to floods and droughts.

The EPA took down its climate change page in 2017, and it never reappeared. The removal of climate change language got a lot of news coverage when Trump’s term started, then quickly dropped off as the issue became old news. “The shock and awe has worn off,” Gehrke said. According to an unpublished paper that Gehrke coauthored, the use of the term “climate change” on the websites of federal environmental agencies went down by 38 percent between 2016 and 2020. Some of the omissions were self-censorship, Gehrke said, from government workers who wanted their climate-related work to escape notice so they could keep carrying it out.

Trump’s first EPA chief, Scott Pruitt, basically admitted in an interview that he wanted to dismantle the agency. In his first speech as administrator, he didn’t mention the agency’s mission “to protect human health and the environment” a single time. Instead, Pruitt talked about getting “back to basics.”

“What he described as ‘back to basics’ was not the basics of EPA — it was not at all going back to what the EPA was envisioned to do, or originally was doing,” Gehrke said. “The EPA began as a hugely powerful force to bear down on polluting industries, and his whole ‘back to basics’ campaign was catering to the regulated industry.” In practice, the EPA weakened or eliminated regulations on natural gas, power plants, gas-guzzling cars, toxic wastewater, and more — essentially giving polluters license to pollute.

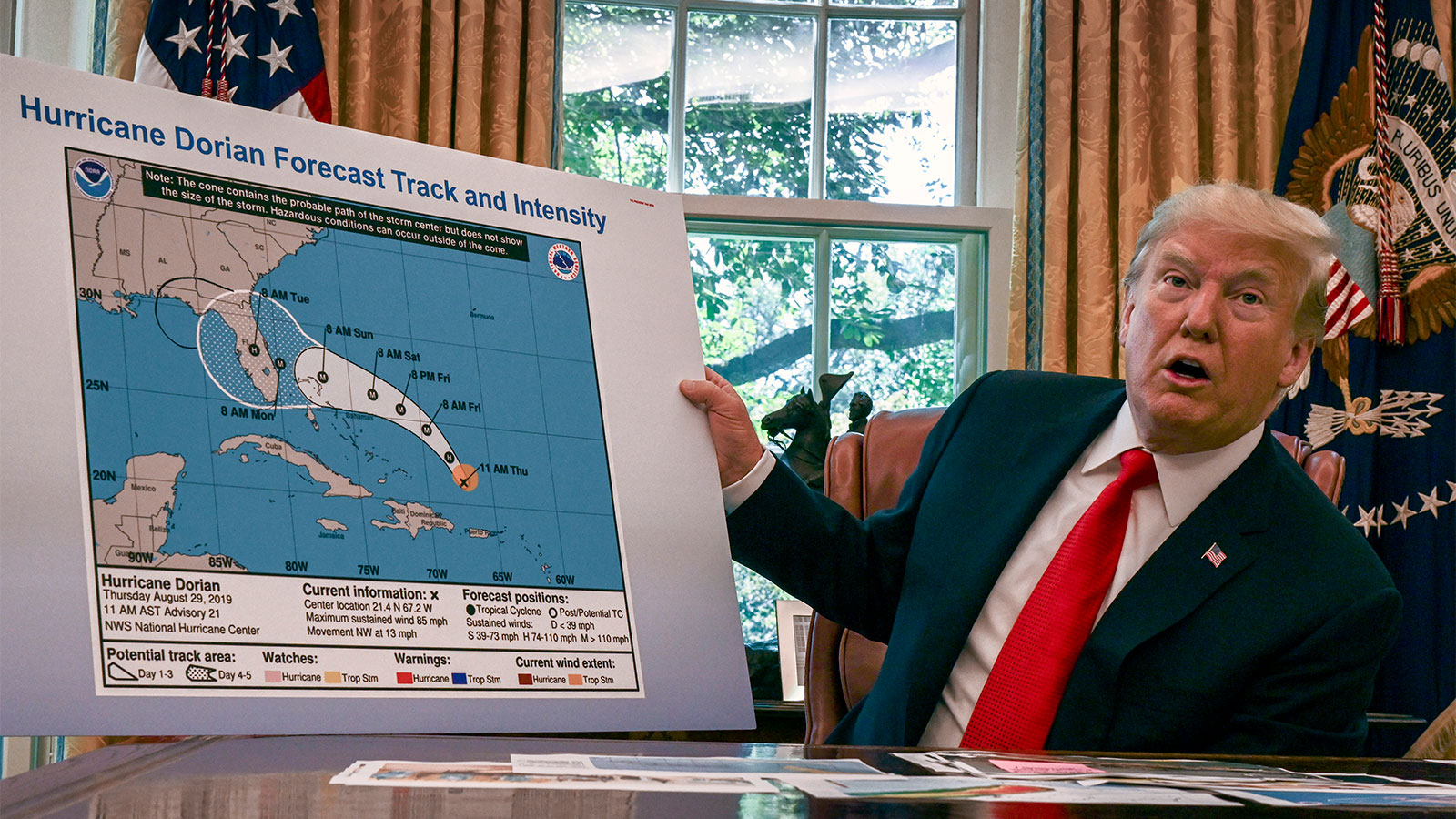

In 2019, as Hurricane Dorian roared toward the Gulf Coast, Trump tweeted a warning to the residents of the Southeast United States, stating, incorrectly, that Alabama was one of the states in harm’s way. Instead of acknowledging the mistake, Trump doubled down. He presented a map of Dorian’s projected path with a Sharpie-drawn loop extending the cone of uncertainty over Alabama. The incident became known as Sharpiegate.

“The essence of Trump is that he has no physical, visceral relationship to anything that he lives within,” said Jean Seaton, the director of the Orwell Foundation. “It’s not just that he just lies — he doesn’t really live a life any of us would recognize … a very narrow nightmare sort of life, really.”

One crucial theme from Orwell’s writings was that to be grounded in reality, people have to share a language — and the most concrete form of language is that which describes the physical world around us, like the weather. “Here’s the thing about Orwell,” Seaton said. “He’s in favor of using your eyes, seeing where you live, being tethered to reality as far as you could be.”

Bill O’Leary / The Washington Post via Getty Images

In the essay Some Thoughts on the Common Toad, Orwell wrote, “I think that by retaining one’s childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies and — to return to my first instance — toads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable.” (Orwell, Seaton notes, doesn’t usually get credit for being an environmentalist.)

By contrast, what Orwell called “political language” in his essay Politics and the English Language, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

According to Masha Gessen, the author of Surviving Autocracy, the slip-sliding of language is a key feature of totalitarian regimes. Gessen, a Russian-American journalist, points to something that the Soviet Union called an “election” — which mandated that people show up at “polling places” and deposit a pre-filled ballot into the box. “Calling this ritual either an ‘election’ or the ‘free expression of citizen will’ had a dual effect: it eviscerated the words ‘election,’ ‘free,’ ‘expression,’ ‘citizen,’ and ‘will,’ and it also left the thing itself undescribed,” Gessen writes. “When something cannot be described, it does not become a fact of shared reality.”

Orwell’s 1984 famously introduced the slogan: “War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.” Real-life politicians, Gessen writes, aren’t usually so obvious about it, defining words with their antonyms. Instead, “they enforce order by applying words in ways that invert meaning.”

If there’s anything encouraging about the Trump administration’s Orwellian language around the environment, it’s knowing that when people speak in ways that are so at odds with reality, that usually means they know that the truth of what they do is unpopular. George Lakoff, a cognitive scientist and linguist, has pointed out that such word games are a sign of weakness on a particular issue, a concession that environmentalists have the moral high ground. Nobody wants to live in a garbage patch and drink lead-poisoned water, after all.

Environmental advocates have done more than fight the Trump administration’s polluter-friendly policies these past four years; they have also sought to sharpen language in parallel. In 2019, progressive advocacy groups urged the media to adopt terms like “climate crisis,” arguing that “climate change was too neutral. A couple of outlets were on the same page, including The Guardian, which had already started using terms like “global heating” and “climate breakdown.” Over the course of the year, the use of the phrase climate emergency increased 100-fold. Perhaps the polluted public discourse fueled this instinct for clarity, just as Trump’s climate-denying presidency ignited more fiery activism.

President Joe Biden plans to rejoin the Paris Agreement and take federal action on the climate crisis. It’s likely his administration will start using clearer language for the catastrophe that has been slowly unfolding all around us. New political eras have often been accompanied by shifts in speech. In ancient China, for example, a ceremony called “the rectification of names” was held at the beginning of each new dynasty to clear up any confusion and erosion of meaning.

Gessen calls for politicians, journalists, and even “kitchen-table debaters” to adopt the habit of defining their terms so that people can “begin the process of restoring language.” Given time, maybe Americans will learn how to understand each other again.