As Maui sweeps up the ashes from America’s deadliest wildfire, water-logged Vermont can’t get a respite from the rain. Meanwhile, Arizona just declared a heat emergency and large swaths of the country are seeing their thermometers climb to levels the government considers dangerous.

Amid 2023’s summer of climate discontent, the nation’s grandest plan yet to rein in runaway greenhouse gas emissions and fight climate change is turning one: the Inflation Reduction Act.

“This bill is the biggest step forward on climate ever,” said President Biden, one year ago today, just before signing the legislation, abbreviated as IRA. That White House celebration came after months of negotiation, and the president’s supporters greeted him with cheers, music, and pomp.

Wide-ranging in scope, the Inflation Reduction Act included changes such as allowing the government to negotiate prescription drug prices and raise taxes on corporations, but at its heart, the IRA is a climate bill. Inside the 730-page bill is nearly $369 billion in spending and tax credits designed to move the United States toward a cleaner energy future. A recent report from the Rhodium Group, an analytics firm that tracks greenhouse gas emissions, estimates that the IRA will reduce national greenhouse gas emissions from 29 percent to 42 percent of 2005 levels by 2030.

Compared to the fanfare that occurred at signing, the year since the IRA was enacted has been outwardly much quieter — with a recent Washington Post and University of Maryland poll finding that 7 out of 10 Americans had heard little to nothing about the measure since it passed. But, largely behind the scenes, experts say that the Biden administration has been implementing the IRA at a scorching pace.

Experts caution against reaching conclusions after the first year of a plan that is meant to span a decade. But they say there are achievements worth marking — such as the torrent of private-sector investment the bill spurred, and the impact it’s already had on Colorado River conservations — as well as future challenges to stay focused on, specifically whether projects can be permitted quickly enough. All the while, the Biden administration must battle not only a divided Congress, but public disconnect from the bill.

Popular and legislative support for further climate action will be key to meeting the White House’s goal of an at least 50 percent emissions cut by the end of the decade. Public ambivalence toward the IRA could be a good thing if the bill falters because it may avoid souring Americans on climate policy writ large, says critic Doug Holtz-Eakin, president of the center-right American Action Forum and former director of the Congressional Budget Office. However, IRA supporters conversely fear that a lack of public awareness about the impacts of the IRA could make passing future climate legislation more difficult.

For now, the administration’s focus has been on making the IRA a success.

“One doesn’t expect the federal government to move quickly, but they have,” said Ramanan Krishnamoorti, vice president of energy and innovation at the University of Houston. After passing the IRA, he doubted the administration could stand up such a massive piece of legislation in such a short period of time. “I was extremely skeptical that they would actually be where they are today.”

The government has spent much of the last year laying the groundwork for dispersing IRA funding and enacting its tax incentives. That has required the government to both revamp old programs, such as the electric vehicle tax credits, and build entirely new ones. Columbia University and the Environmental Defense Fund have so far logged 150 IRA-related actions that the federal government has taken, ranging from the Environmental Protection Agency awarding climate pollution reduction grants to the Department of Agriculture opening applications for its rural-energy-in-America program.

“We’ve been thinking about year one as phase one of the IRA,” said Holly Bender, chief energy officer at the Sierra Club. She said the government has had to stand up hundreds of new funding streams, programs, and teams within federal agencies. That effort, she said, has been “incredibly successful” and puts the government in a position to “have the money start flowing out the door.”

But Holtz-Eakin doesn’t see the administration’s ability to distribute IRA funding as an inherent measure of effectiveness. “It’s easy to shovel money out the door,” he said. “They’re far from done.”

There have, however, been some more immediate, tangible results of the legislation.

On a pragmatic level, the federal government has been adding staff in order to implement the legislation. This is true at climate-facing entities such as the Department of Energy, but also agencies that are less-often linked to climate policy, including the Treasury, which is charged with outlining the rules for the litany of tax incentives that the law called for.

Krishnamoorti also highlighted another overlooked aspect of the IRA: its impact on the Colorado River. The IRA included $4 billion for water management and conservation efforts in the Colorado River Basin, which has already helped states settle long-fought negotiations over how to reduce water use in the river. The agreement reached this May allocated $1.2 billion to cities and irrigation districts in Lower Basin states in exchange for them using less water.

“The agreement that the states came to was in large part because they anticipate this funding coming,” said Krishnamoorti.

But experts agree that perhaps the most pronounced first-year effects of the IRA has been a deluge of investment announcements from the private sector. Just last week, for instance, Maxeon Solar Technologies publicized a $1 billion plan to manufacture solar cells and panels in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

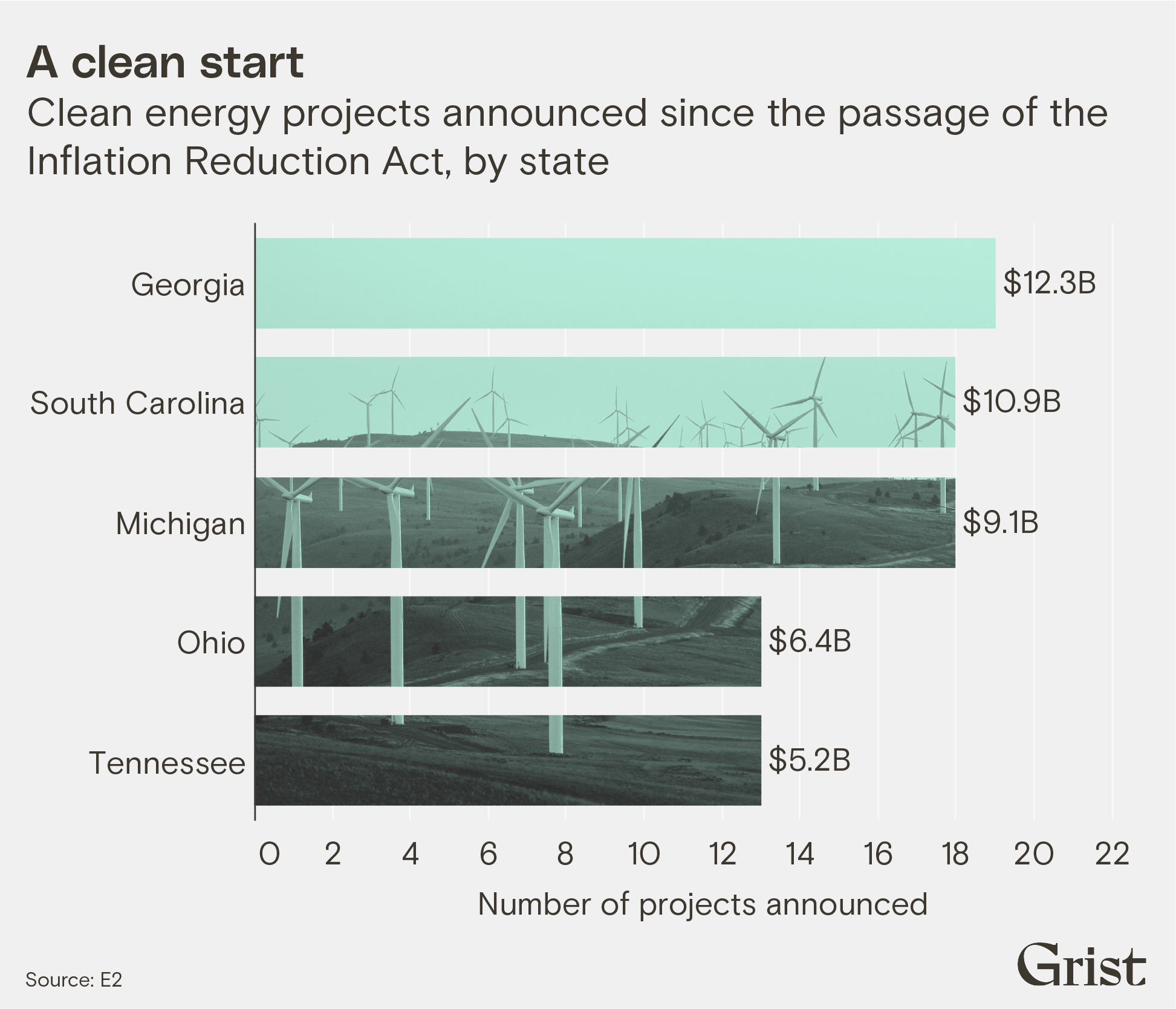

Overall, companies have trumpeted more than $86 billion in IRA-related investments since the bill was passed, according to E2, an organization that has been tracking businesses’ response to the legislation. The White House puts that number even higher, at $236 billion of planned investments in the electric vehicle, battery, and clean energy sectors, where the commitments have been particularly pronounced.

“The responsiveness of industry to these new incentives and financial support I think demonstrates the depth of the appetite for an American manufacturing renaissance,” said Trevor Higgins, senior vice president at the Center for American Progress think tank. He was previously a member of California Senator Dianne Feinstein’s staff and helped shape the IRA.

To a certain extent, companies were already moving toward a lower-emissions future, so it’s hard to pinpoint exactly how much of the IRA is driving the investment decisions. But many businesses and politicians have specifically cited the legislation as motivation. In West Virginia, companies have broken ground at two major battery manufacturing sites.

“These types of investments are exactly what I had in mind when I wrote the IRA,” West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, a key swing-vote on the legislation, said in a statement. He also vowed to “continue to fight the Biden Administration’s unrelenting efforts to manipulate the law to push their radical climate agenda.”

Manchin’s home state of West Virginia is set to see some $1.3 billion in private-sector dollars from the IRA, according to E2 data, and four of the top five states where investments are planned have Republican governors. Supporters of the IRA say that projects in Republican-led states will at least partially insulate the bill from politically motivated rollbacks.

“Any administration that comes in and reverses IRA provisions will lead to a lot of job destruction, primarily in red states,” said Anand Gopal, executive director of policy research at Energy Innovation Policy & Technology, a energy and climate think tank.

Republicans have nonetheless tried to dismantle aspects of the IRA since taking control of the House this year. According to Roll Call, at least four House bills have taken aim at the IRA, especially the EPA’s $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. And until projects are fully funded and physically built, many of the first-year impacts of the IRA remain vulnerable to a shift in political winds.

In some ways, the IRA could also prove to be a victim of its own progress. Bender, with the Sierra Club, says that the sheer number of new programs has been difficult for eligible entities to navigate. There’s a big capacity gap she said, especially for smaller nonprofits or companies.

“It’s [difficult] to find a person who can understand the programs, read the eligibility criteria, check the application dates, and then apply for funding,” she said, adding that the Sierra Club is working with its partners to “make sure that anyone who wants to access IRA programs is able to do so without a huge administrative burden.”

Then there’s the actual, physical building that needs to happen. Once a project is approved for funding or credits, worries shift to whether it will run into regulatory snags such as permitting. Easing that process is an area experts say the administration has not made much headway on in the first year of the IRA.

“The most likely bottleneck going forward is going to be permitting,” said John Coeqyut, the federal policy team director at RMI, a nonprofit working to accelerate the clean energy transition. “We are concerned that not enough will be done to clear the way for the transition.”

John Podesta, who Biden tapped to lead the administration’s IRA efforts, addressed so-called permitting reform in remarks in May. “We’ve seen some recent wins,” he said, pointing to the Department of Energy’s move toward accelerating electricity transmission line permitting. But he also called on Congress to pass reforms that have been hung up for months.

“This administration is doing all we can with the tools we have,” said Podesta. “But frankly, we could use more tools to go even further and faster.”

As far as getting more legislation passed, the administration is up against both a divided Congress and limited public awareness about the effects of the IRA. Less than a third of Americans say they’ve heard of the bill since it passed and even Biden acknowledges that the IRA has thus far failed to grab people’s attention.

“I wish I hadn’t called it that,” he said at a fundraiser in Utah last week. “It has less to do with reducing inflation than it has to do with providing alternatives that generate economic growth.”

Critiques from environmentalists about the bill’s concessions to fossil fuel interests also remain unresolved after year one. There are, for instance, outstanding questions on issues such as hydrogen tax credits, the wording of which could affect the climate impacts of the IRA because it could encourage investment in fuels that are derived from natural gas versus renewable energy. “That one is taking a little bit more time,” said Gopal. “But I think rightfully so.”

That said, there is hope among advocates that Americans will begin to feel the impacts of the IRA more directly in year two. Perhaps most notably, the Department of Energy has issued guidance for a range of home energy rebates that states are expected to begin dolling out over the coming year.

“These rebate programs are really important, because they are a way for low and moderate income households to be part of this transition,” said Ari Matusiak, CEO of Rewiring America, an electrification nonprofit. “We want to make sure those programs are being stood up and well utilized by the people who can most benefit from them.”

The ultimate test of the IRA, though, will be how quickly and how deeply it reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Holtz-Eakin says he’ll be watching the Energy Information Administration’s annual release of data as a gauge for the amount of renewable energy being brought to homes and businesses across the country. “If that hasn’t moved by year three, the advocates are going to start getting nervous,” he said. “How quickly can you move the needle, and as a result retain the support you have?”

Anand Gopal, with the Energy Innovation Policy & Technology, says the IRA remains on track to meet his organization’s projection that the bill will cut emissions by 37 percent to 41 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Nothing in the first year of the IRA, he says, has changed that trend toward a cleaner energy future.

Former South Carolina Representative Bob Inglis, a Republican, was once a climate change skeptic and is now a champion of climate solutions. To him, whether the IRA gets credit for the transition or not doesn’t detract from the progress it will likely lead to.

“When people start seeing it rollout in projects, they won’t know that it came from the IRA,” Inglis said. “[But] the IRA is going to deploy a lot of wind and solar and that’s an accomplishment that people are going to look back and be proud of.”