Is it better to take on climate change with bold, revolutionary action, or compromise and tinkering?

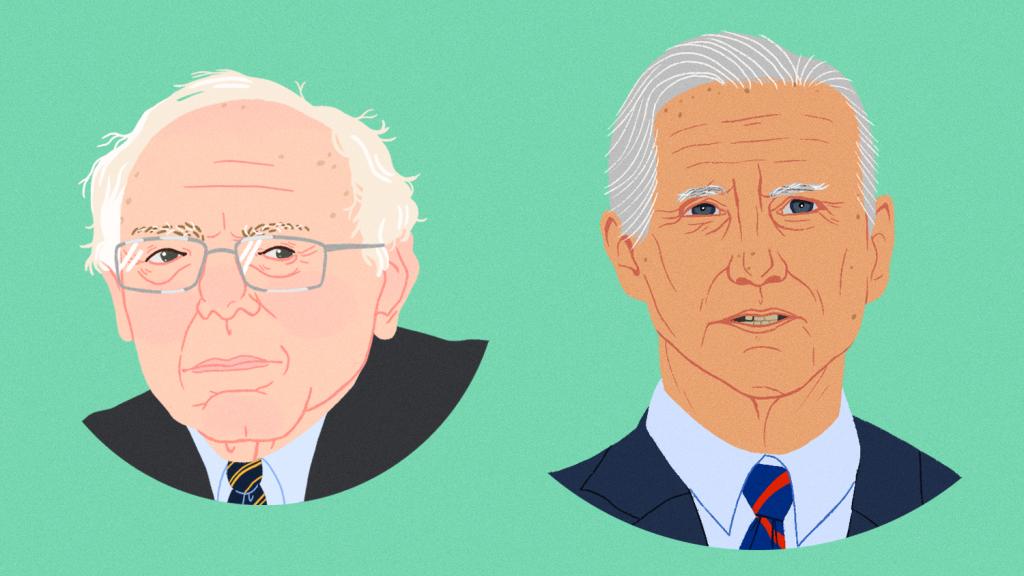

In practice, it’s usually both. You can organize protests, and support the incremental art-of-the-possible tweaks that city and state officials work to pass. But in the contest to nominate the Democratic candidate for the White House, this question has been an either-or proposition. The race has narrowed to Senators Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden, who represent opposite sides of this divide (or at least their supporters do). You’re bound to see this populist versus insider split when they face off in debate Sunday.

Sanders promises big, Green New Deal-style changes, counting on a popular uprising to transform political reality. Biden, though also a supporter of the Green New Deal, offers more modest changes within the existing political framework. Which is a better bet?

In the middle of our national flame-throwing fest about how to get things done, we could learn a lot from a little-noticed debate from last year that serves as the perfect proxy for this question. This wasn’t your typical chest-pounding debate, in fact it was sort of the opposite: A disagreement offering so much clarity that, no matter your position, it’s certain to shift your thinking at least a little bit.

It started in March last year, when Jerry Taylor, president of the Niskanen Center, pleaded in “An Open Letter to Green New Dealers” for a more Biden-esque approach. (Taylor is a former CATO Institute climate-change skeptic who changed his mind as he reviewed the evidence).

Leah Stokes, a professor of political science at the University of California at Santa Barbara (and a newly minted member of the Grist 50) fired back with an epic thread of tweets, making the Bernie-esque case that elected officials would need a social movement, a push from the people, to get anything done.

The two met in person last September and hashed it out at a conference organized by the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental think tank. You can watch the whole debate yourself.

But if you’re trying to limit your screen time, here are some of the highlights:

Taylor warned Stokes against fighting the impossible fight. He anticipated that a political window would open to pass climate legislation in 2021, which Democrats could miss if they become focused on the Green New Deal. There’s good reason to think something that big would fail: The Democratic Congress couldn’t even pass a resolution to support it in principle.

“In other words, if there was a Republican rapture experience, and they all disappeared and all we had were Democrats in the House, it still wouldn’t pass,” Taylor said.

It turned out that Stokes agreed with this: “A lot of your critiques, Jerry, really speak to the inside Congress game. And I think you are spot on on that.” But she argued that if there’s going to be any hope of passing legislation big enough to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions, we should be looking outside of Washington for leadership. “If you look at the Earth Day movement, the founding of the EPA, the Clean Air Act, a lot of the landmark legislation that we still rely on today actually came out of a big public outpouring of people in the streets,” she said.

The problem with Stokes’s line of thinking, Taylor responded, is that climate action is polarized along political lines. Republicans such as climate-change denying Senator James Inhofe are the ones blocking legislation, he said, not the politicians influenced by climate strike-leader Greta Thunberg. “I don’t care how many people Greta puts in New York, it’s not changing James Inhofe’s mind, nor is it changing the votes of most Republicans.”

But the fact that activists, like those from the Sunrise Movement, are banging down the doors of Congress and holding strikes is creating space even for right wingers to offer their own version of policy, Stokes said. “If you are being asked by journalists all the time, like, “What’s your climate plan?” and the Republicans have no answer, they have to come up with something.”

There’s much more to be gleaned from the debate (you really should watch it, these two are so funny and smart) Witness Taylor ripping the GOP (“First of all, you have to speak their language: Russian”) and Stokes self-mockingly professing her passion for energy research (“I just want to spend a lot of money because I love the government, bad habit”).

It’s important to recognize that a lot has changed in the last 4 months. When I recently asked Taylor for an update, he pointed out that the Green New Deal is no longer sucking all the air out of the room, so the door is open for politicians to push for other measures in Congress. Democrats are working on bills like the Clean Future Act which, he said, is less a Green New Deal and more a copy of California’s state climate policy rejiggered for national scale.

Taylor also had words of praise for the activists he had once been so worried about. “What Sunrise has done,” he said, “is to elevate climate change to the near-top of the progressive agenda. And that counts for something. It may count for a lot, actually.”

Which is one of the key points Stokes was making in their debate. Taylor shifted his stance as he realized the facts had changed. As for Stokes, she noted that this primary season is a referendum on whether activists like the Sunrise Movement can lead a surge in new voters to support something like the Green New Deal. That hasn’t happened. “I think we are seeing the limits of that,” she conceded. Both Taylor and Stokes have moved closer to each other.

But Stokes stuck to her guns on one point: She sees a role for a social movement around climate change. “I think that climate change is the unity issue for the Democratic Party. And it’s a huge wedge issue: It has a lot of support among independents and young Republicans.”

A smart candidate would run on a climate-focused surge of spending, promising good union jobs and clean air, Stokes said: “That would be a winner in November.”