It was the winter of 2015 and Ken Paxton, the newly elected attorney general of Texas, stood before a lunchtime crowd of conservatives at the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s downtown headquarters in Austin. He was giving an opening keynote on “The Clean Power Plan, the War on Coal, and Why I Sued the EPA” alongside coal baron Robert Murray.

Paxton was in familiar company. The foundation, a right-wing think tank, had organized an energy and climate policy summit and stacked it with a who’s who of climate deniers. Over the next two days, attendees would sit in on discussions that touted carbon dioxide as the “gas of life” and condemned the federal government’s efforts to “shackle energy.”

As the sounds of clinking cutlery filled the room, Paxton broadcast what would become the defining crusade of his tenure: repeatedly suing the federal government — in particular over environmental regulation.

“Governor [Greg] Abbott told me as he swore me in, and I put my hand down, he said, ‘You will be the busiest attorney general in Texas history,’” Paxton recalled. “We’ve actually sued the Obama administration now six times,” he added to applause.

Paxton’s political rise was swift; he went from state representative to state senator to attorney general in just three years. Brasher and more brazen than even his arch-conservative predecessor, Abbott, Paxton would become a prominent ally of President Trump.

He shared not only the former president’s anti-environmental and anti-immigration views, but also his Teflon-like quality for deflecting his own legal troubles. Less than six months into his first term as attorney general, Paxton was indicted for securities fraud for allegedly persuading investors to buy stock in a tech firm without disclosing that he was being paid by the company to promote its services. He managed to escape trial for the next eight years, all the while maintaining the support of the Texas Republican party and the state’s voters, handily winning re-election in 2018 and 2022.

Like Trump, however, Paxton’s brazenness is now catching up to him. The attorney general’s undoing began in 2020, when senior officials in his office alleged that he had used his elected post to serve the interests of real estate investor Nate Paul, a friend and campaign donor. According to the staffers, Paxton directed his office to investigate Paul’s rivals; in return, Paul allegedly helped him remodel his Austin home and hired a woman with whom Paxton was having an affair. When Paxton fired the employees who spoke out, they filed a whistleblower lawsuit for retaliation. That suit was settled earlier this year for $3.3 million. (Paxton has denied all allegations by the whistleblowers.)

Texas taxpayers were on the hook for that payout — a fact that didn’t sit well even with the lawmakers who had previously turned a blind eye to Paxton’s indiscretions. By then the federal Justice Department had also begun investigating the whistleblowers’ claims, and his own party finally turned on him. In May, legislators in the Texas House voted to impeach Paxton by a count of 121 to 23, a stunning rebuke from the Republican-led chamber. His trial in the Texas Senate begins on Tuesday.

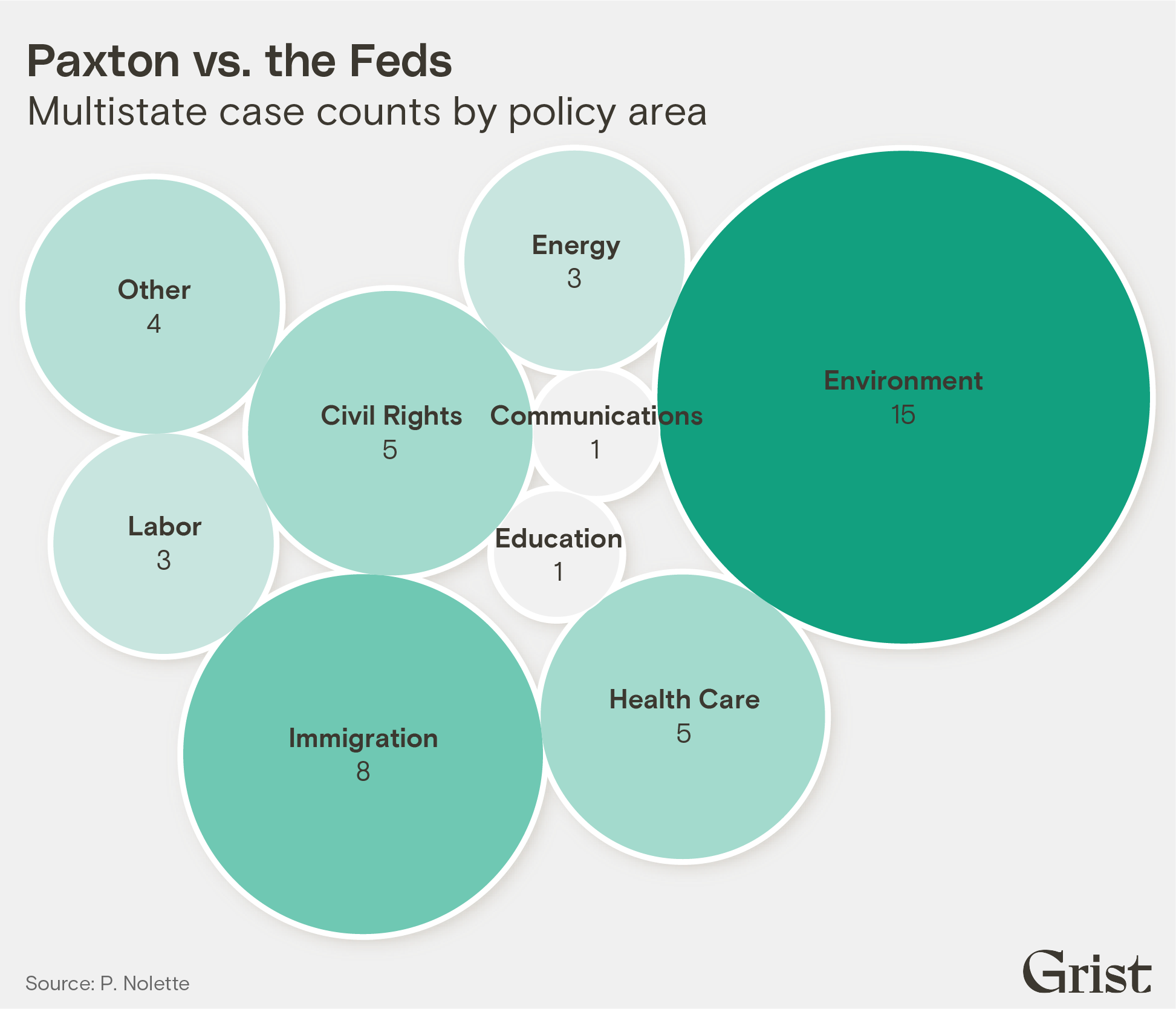

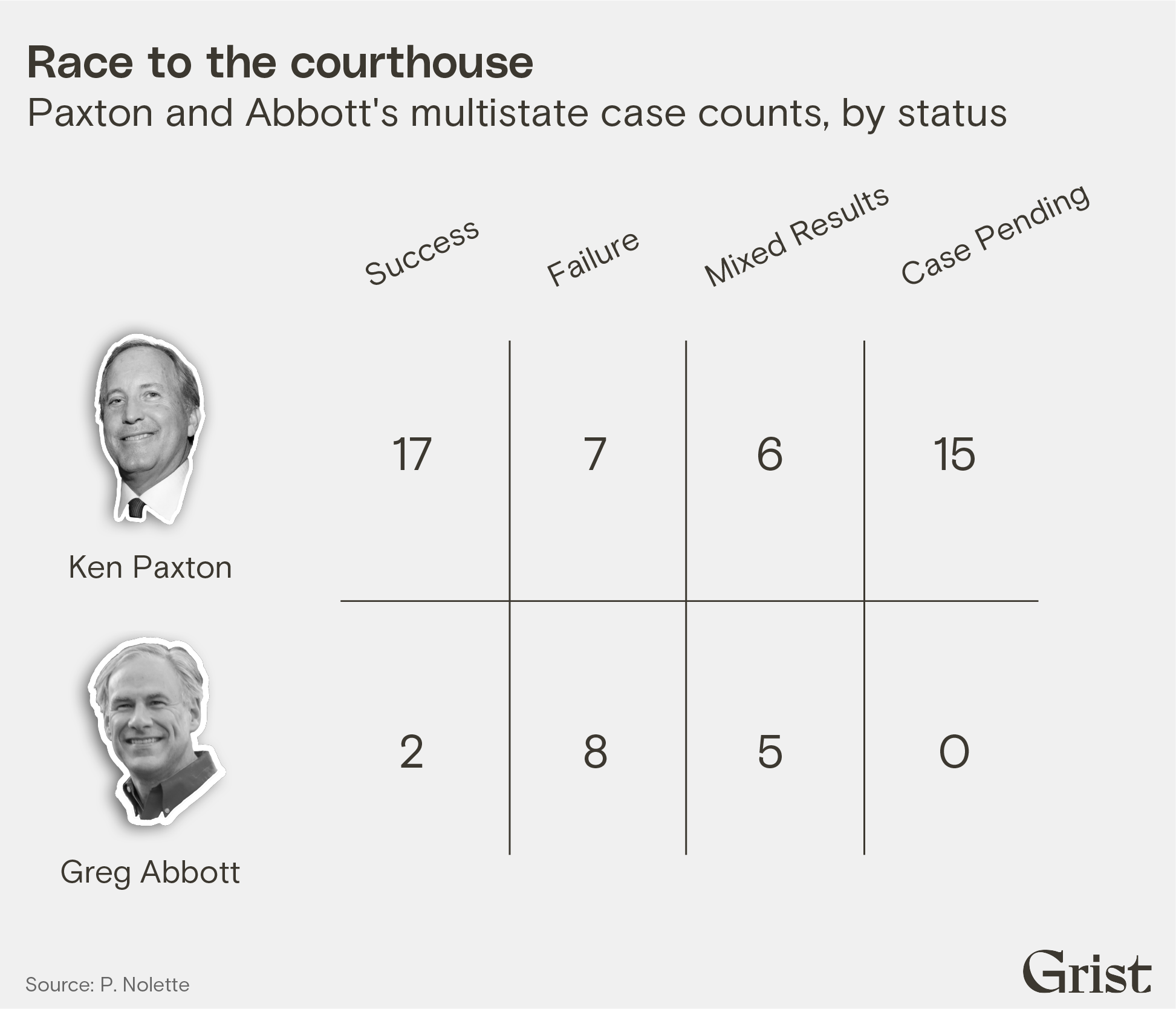

Nevertheless, Paxton fulfilled Abbott’s prediction that he would be “the busiest attorney general in state history.” During his eight years in office, Paxton participated in multistate lawsuits against the federal government 45 times, a rate three times that of Abbott. Nearly half of those cases concerned energy or environmental issues, and they fought to stop rules that would have reduced carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, increased protections for rivers and streams, cut pollution from cars and trucks, and applied other environmental protections.

At the same time, Paxton centralized state authority over environmental litigation in the attorney general. His office backed legislation requiring community groups and counties to give the attorney general first dibs on environmental lawsuits. The resulting law has hamstrung environmental groups and county attorneys in Houston and Port Arthur from suing major polluters. Local officials and environmental advocates say that Paxton’s office has in turn let companies off with just a slap on the wrist.

As a result, Paxton’s tenure has been “a disaster for Texas’ air, water, and climate,” said Luke Metzger, executive director of the nonprofit Environment Texas. (Paxton’s office did not respond to a request for comment.)

State attorneys general suing the federal government is not a new phenomenon, but Paxton has been one of the most adept at using lawsuits to influence federal policy. After Democratic attorneys general first found success suing the Bush administration in attempts to force it to address climate change, Republicans increased the popularity of the tactic by batting back federal rules through lawsuits against the subsequent Obama administration. Texas was at the forefront of this type of litigation.

As a state with significant fossil fuel resources, the country’s largest petrochemical hub, and a concentration of conservative judges who may be sympathetic to fossil fuel and business concerns, Texas became an ideal venue to file cases challenging environmental regulation. During Abbott’s time as attorney general, Texas joined in 15 multistate lawsuits and filed 28 other independent lawsuits against the federal government. Abbott famously described his job as such: “I go into the office, I sue the federal government, and then I go home.”

Though Abbott lost more than half of the multistate cases, Paxton has had much more success: Texas has won more than 40 percent of the 45 multistate cases it has filed since Paxton took office in 2015.

“Paxton has been very aggressive, much more so than Abbott, in going to the courts that are the most favorable,” said Paul Nolette, a political science professor who studies attorneys general at Marquette University. Nolette calls this “platform shopping” — cherry-picking venues with sympathetic judges. “The fact that platform shopping has gotten so much more prominent is a big reason why they’ve seen more success — definitely at least at the district court level, if not on appeal,” Nolette added.

In multistate cases, states can file suit in any federal court in any one of the states involved in the litigation. As a result, states have wide latitude in picking the venue where their legal arguments will be heard. Increasingly, Paxton’s office has chosen to file in one Texas court: the Amarillo division in northern Texas.

According to a recent Justice Department brief, Paxton has sued the Biden administration 28 times in various Texas courts. Of those, 18 were filed in Amarillo, a division with a single judge. The issue came to a head in a recent lawsuit filed by Texas and other states over new Labor Department rules that give retirement-plan sponsors more leeway to consider environmental, social, and governance factors when considering investment options. Paxton and other attorneys general filed suit against the federal government in the Amarillo division, and the case landed before Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk, a Trump appointee.

In February, the Justice Department filed a motion to have the case reassigned to another judge. “Plaintiffs’ and other litigants’ ongoing tactic of filing many of their lawsuits against the federal government in single-judge divisions, or divisions where they are otherwise almost always guaranteed to procure a particular judge, undermines public confidence in the administration of justice,” attorneys for the Justice Department noted in a brief.

Nolette, the political science professor, also attributed Paxton’s success to the fact that staff in the attorney general’s office are increasingly involved in federal rules earlier on. Staff attorneys often file comments during the rulemaking process, which gives them a longer lead time to develop arguments that can eventually be used in lawsuits that are filed after the rules are finalized. While it previously took months for attorneys general to file suit after a rule got on the books, now lawsuits are filed within days of a rule being finalized. In the last year, Paxton’s office has sent letters to the EPA opposing proposed new clean air standards and updated environmental rules for the oil and gas industry.

Nolette attributes Paxton’s success to aggressive tactics like these. “He’s been savvy in that way, at least in terms of being able to make the most out of the opportunities that are in front of him,” he said.

Paxton’s savviness also extended to environmental lawsuits at the local level. The attorney general is the top cop in the state. Paxton used this feature of the hierarchy to police the actions of county attorneys, who can bring civil environmental cases against polluters. In 2017, Paxton’s office pushed for legislation that required local entities (including community groups filing citizen suits) to provide a 90-day notice to the attorney general’s office before filing suit. The attorney general could then intervene and take over the case.

The bill was passed after it was revealed in 2015 that Volkswagen had installed defeat devices in 11 million vehicles sold worldwide to cheat emissions tests. Attorneys across the world rushed to file suit against the German carmaker for defrauding the public. In Texas, then-Harris County Attorney Vince Ryan was among the first to sue Volkswagen. For years, Harris County had been in “non-attainment” of the Environmental Protection Agency’s smog standards. Ryan argued that by installing defeat devices that masked the true level of nitrogen oxide emitted by its cars, Volkswagen had prevented the county, which includes the city of Houston, from meeting the EPA’s air quality standards.

Paxton, however, wanted the matter solely in his hands. He requested that Ryan drop Harris County’s lawsuit and let the state “achieve a comprehensive and just statewide resolution of this matter on behalf of Texas.” When Ryan refused, Paxton turned to state lawmakers, who passed the law requiring local entities to give his office 90 days’ notice before filing environmental lawsuits. Paxton could then determine if he wanted to take over the case, thereby barring local groups from bringing the suit themselves.

“The bill will provide consistency in interpretation of state law and regulation,” Craig Pritzlaff, an attorney in the environmental protection division of the attorney general’s office, told lawmakers at a legislative hearing in 2017.

But local attorneys’ offices and environmental groups saw the legislative push as yet another effort by the state to limit consequences for polluters. In 2015, the state had passed a law that capped the penalties that counties could collect from environmental violators at about $2.2 million. The law was a direct response to Harris County suing three companies for allowing dioxins to leak into the San Jacinto River and Galveston Bay for decades. Two of the companies eventually settled for $29.2 million, one of the largest civil penalties for solid waste violations in the state.

The 2015 and 2017 laws limiting when local entities could bring environmental lawsuits and how much they could collect in penalties typified the battle between local city governments that tended to lean Democratic and state leaders, who were Republican. Those laws also came on the heels of the state legislature overturning the city of Denton’s ban on fracking.

The 2017 law “essentially ended the period of aggressive civil litigation of the county,” said Terence O’Rourke, a former special assistant in Ryan’s office. Another 2019 law requires county attorneys to seek permission from the attorney general’s office when hiring outside counsel. Since counties have limited staff and resources and may not have the expertise to bring specialized cases, they often hire lawyers in private practice on contingency fee contracts to represent their interests. After these laws were passed, O’Rourke said the county was only able to bring cases through backdoor political maneuvering.

For example, when Harris County wanted to file suit against the e-cigarette manufacturer Juul, it retained a group of lawyers with Republican connections, O’Rourke said. One lawyer was a former Texas Supreme Court justice; the political connections helped the office get the approval to hire outside counsel and file the case.

“We got in the door on that one,” O’Rourke recalled. “That’s reality. How do you make it through and not have them taken over before they even begin?”

Grist obtained a list of 90-day notices sent to the attorney general through a public records request. Since the law passed in 2017, Paxton’s office has received 100 such notices; 62 were filed by Harris County. Of the 62 cases, the attorney general’s office has intervened in at least nine. While the number of times the office has intervened remains low, Paxton’s office appears to take over cases when they involve larger corporate polluters. The vast majority of cases in which Harris County has been allowed to take the lead involve small mom-and-pop operations, midsize chemical companies, and waste-disposal companies.

“Whenever we get a large-scale emissions event, they take the case,” said Harris County attorney Christian Menefee. “That is just kind of a regular occurrence, and these cases often end up getting settled for pennies on the dollar.”

For instance, when a waste-processing facility had a fire in 2021, the state took over the case from Harris County and settled for a $11,250 administrative penalty — 3.75 percent of the $300,000 statutory maximum. In another case involving a fire at a bulk liquid-storage facility the same year, the state environmental agency settled for about 1 percent of the more than $1 million maximum statutory penalty.

“It’s very clear that there’s a concerted effort in the [attorney general’s] office with the [state environmental agency] to take these cases from local governments and then to settle for 3 or 4 or 5 percent of the statutory maximum,” said Menefee, “instead of truly seeking the amount that’s going to be representative of the harm that was done to these communities, and that’s going to disincentivize companies from allowing these things to continue to happen.”

At least three cases have also stalled in the courts. After receiving much publicity for suing polluters responsible for massive fires and air pollution in 2019 and early 2020, lawsuits against Intercontinental Terminals Company, Valero, and TPC Group have languished in the courts. Grist’s review of the filings shows that few preliminary legal documents have been submitted to the courts over the last three years. The lawsuit against Valero was initially planned by environmental groups including the Sierra Club, Environment Texas, and the Port Arthur Community Action Network. The Sierra Club has had success filing similar lawsuits against polluters. In 2017, the group’s lawsuit against another Exxon facility resulted in a $20 million penalty.

“Four years is a long time to go on with litigation like this with little to show for it,” said Environment Texas’ Metzger. “We’re very concerned that the attorney general’s office isn’t aggressively litigating these cases.” If the environmental groups had been allowed to proceed with the cases, he argued, the lawsuits would’ve gone to trial and received verdicts by now.

Menefee said that his office has used creative legal strategies to get around the attorney general’s office, including citing federal environmental laws and suing in federal court. When the Texas Department of Transportation planned an expansion of a major highway that would harm communities of color, Menefee said his office chose to file a lawsuit against the agency under the National Environmental Policy Act in federal district court.

Similarly, when a cancer cluster was discovered in Houston’s Fifth Ward, Menefee said the agency notified the company responsible that it would sue under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, a federal hazardous waste law. But suing under federal laws in federal court comes with significant downsides. Bringing a case before a federal court is time-consuming, costly, and cumbersome.

On the other hand, convincing the attorney general’s office to allow the county to bring its own case requires the expenditure of significant political capital, Menefee said. “Each time that I have to go up and ask them for their permission, there’s a price,” he said. Ultimately, it means that the county cannot pursue polluters as vigorously as it might otherwise.

“It’s demoralizing, and it’s harmful to Harris County communities, because now they don’t get to have their day in court on environmental issues,” Menefee said.