President-elect Donald Trump has put forth a slate of Cabinet nominees that reflects a clear commitment to fossil fuels and upending the country’s efforts to address climate change.

The eclectic group includes TV personalities, industry insiders, and climate skeptics. If confirmed, they are expected to promote fossil fuels, environmental deregulation, and hostility toward climate science. They will also likely stymie the expansion of renewable energy and the adoption of climate-friendly technologies.

Of course, the clean energy transition has built up some momentum that even the Trump administration cannot stop. State and local governments are preparing to take up the mantle as well. But Trump clearly intends to use the full weight of federal authority to reverse the climate initiatives of the Biden administration and slow or stall further efforts to mitigate the crisis. Such efforts would add billions of tons of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

Grist has unpacked the background of the Trump Cabinet nominees who will have an especially significant impact on federal climate policy, the public, and, ultimately, the planet.

Department of Energy

Andy Cross / Getty Images

The energy secretary plays a vital role in shaping the nation’s energy policy and, therefore, its response to climate change. The nominee, Chris Wright, would manage a sweeping portfolio, giving him oversight of everything from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to federal research into energy technologies. His department also would be charged with setting home-appliance efficiency standards for millions of Americans.

Wright has deep roots in the fossil fuel industry. He leads the world’s largest fracking company and has extensive experience with shale gas extraction. In a video posted to LinkedIn, he said, “There is no climate crisis, and we’re not in the midst of an energy transition, either.” He concedes that climate change is “a real issue,” but calls its impacts “clearly overwhelmed by the benefits of increasing consumption” of oil and gas.

While critical of wind, solar, and a transition to cleaner energy in general, Wright has shown support for geothermal energy, nuclear power, and carbon sequestration, and the Energy Department may bolster its support for those areas under his watch. But he is also poised to incentivize fossil fuel production by pushing for further deregulation of the sector, and to do little to advance an “energy transition,” a term he calls “deceptive.”

— Tik Root

Environmental Protection Agency

Kevin Dietsch / Getty Images

The appointment of Lee Zeldin to lead the Environmental Protection Agency has profound implications for fossil fuel production, the clean energy transition, and the nation’s ability to mitigate the impacts of a warming world. Beyond setting emissions standards and enforcing environmental regulations, Zeldin would decide how much of the agency’s $12 billion budget to spend on climate mitigation and adaptation, industrial oversight, and green energy development.

During his eight years in Congress, Zeldin regularly voted against progressive climate and environment policies — including the Inflation Reduction Act, which he said “sucks” — earning him a score of just 14 percent from the League of Conservation Voters. Zeldin is a chair at the conservative America First Policy Institute, which has called the Paris Agreement “lopsided” and endorsed opening the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge to drilling.

He plans to quickly roll back regulations to advance Trump’s economic agenda. Among his likely targets are Biden-era initiatives loathed by fossil fuel companies, including air monitoring around refineries and tighter pollution limits. Zeldin has waved at the importance of clean air and water, but offered no indication of how the EPA will ensure those things alongside a smaller budget and diminished rules — a sign of tough times ahead for communities fighting for environmental justice.

— Lylla Younes

Department of the Interior

Until his nomination, Doug Burgum was best known for selling a billion-dollar software company before becoming North Dakota’s governor in 2016 and launching a failed bid for president last year. As Interior secretary, Burgum would oversee federal oil and gas leases and play a key role in fulfilling Trump’s promise to open more lands and waters to drilling. He also would be in charge of national parks and monuments, federal wildlife refuges, and policies affecting Indigenous peoples. Also within his purview: presiding over a new National Energy Council that, according to Trump, will “oversee the path to U.S. ENERGY DOMINANCE.”

Burgum has acknowledged the reality of climate change and has backed some Biden administration green energy subsidies that Trump opposes. He’s even called for making North Dakota carbon neutral by 2030 and has made a concerted effort to improve tribal relations.

That said, Burgum supports the current route for the Dakota Access Pipeline that is opposed by the Standing Rock Sioux, and his close friendship with an oil and gas industry titan Harold Hamm and major financial investments in the industry worry environmentalists, who expect the Trump administration to aggressively drill, even at the expense of sacred lands and the future of the planet.

— Anita Hofschneider

Department of Agriculture

Tom Williams / Getty Images

The U.S. agriculture secretary is an understated but influential position that shapes the future of a food system that is contributing to, and reeling from, climate change.

If confirmed, Brooke Rollins, a lawyer who grew up on a farm, would lead an agency that is the backbone of food security and safety, an essential provider of disaster assistance and safety net programs, and a driver of rural development. The USDA also helps address climate change through land conservation, agricultural research, forest management, and its promotion of sustainable farming.

Rollins currently leads the America First Policy Institute, a conservative think tank. She holds a degree in agricultural development, but has limited working experience in food or agriculture. A longtime Trump ally who served in several roles in his first administration, including a stint as acting head of the Domestic Policy Council, there’s no question whether she will advance Trump’s agenda.

That agenda is likely to include sweeping tariffs, which in Trump’s first term led to trade wars that decreased farmer profits so substantially the federal government had to bail out farmers with massive subsidies. If she’s confirmed as agriculture secretary, Rollins would be involved in renegotiating key trade deals. Rollins is also likely to help advance Trump’s goals to deregulate the agriculture industry, curb food-assistance programs, and roll back sustainable ag funding and research.

— Ayurella Horn-Muller

Department of Transportation

Steven Ferdman / Getty Images

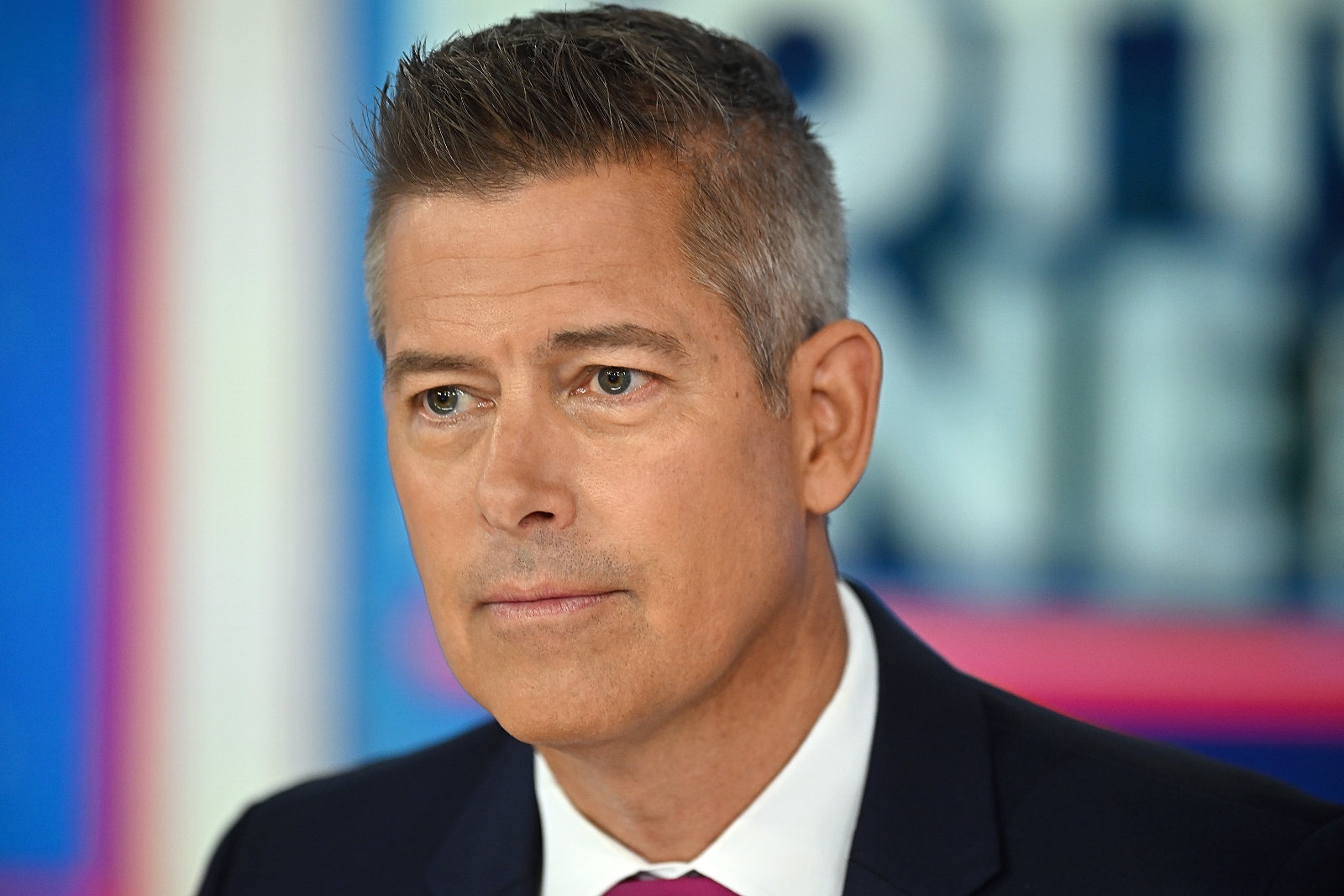

Transportation accounts for nearly one-third of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, giving the agency Sean Duffy may lead a broad climate mandate. As secretary of the department, the former lawmaker would oversee the allocation of transportation infrastructure and mass transit funding. He also would support the development of alternative fuels and any advancement of the EV transition that might continue under Trump.

The one-time star of MTV’s The Real World spent nearly nine years in Congress, where he served on the House Financial Services Committee, but his most recent experience is as a Fox News personality.

It remains unclear how he’ll approach key issues like infrastructure, which tends to be relatively bipartisan, but he has called the Biden administration’s support of electric vehicles “the dumbest policy.” That does not bode well for the fate of Biden’s plan to roll out 500,000 public EV chargers by 2030.

Duffy won’t be able to change tailpipe emissions standards (that’s the EPA), but he can likely hamper the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program and limit EV research. It also remains to be seen how he’ll handle maritime and aviation emissions, including developing more sustainable jet fuels.

— Tik Root

Department of Health and Human Services

The nation’s top medical science institutions may soon be led by a conspiracy theorist.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the other agencies within the department that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. hopes to lead do more than safeguard public health. They are key to understanding how climate change drives infectious disease.

Even as that work grows more essential, Kennedy wants to reorient the department to eliminate what he calls “corporate corruption.” He believes, among other things, that vaccines cause autism, Wi-Fi signals are carcinogenic, and antidepressants contribute to school shootings. Kennedy would shift research away from infectious diseases and toward chronic and genetic conditions. That’s risky, since climate change is fostering the spread of Lyme and other ailments carried by ticks, mosquitoes, bacteria, and fungi. The last time the CDC decided to veer away from such work, it was humbled by the AIDS epidemic.

It is unclear how much Kennedy could accomplish, because many of his goals require congressional approval or are beyond the department’s purview. But it is clear that, if he is confirmed, seismic changes are coming to how the government studies and ensures public health.

— Zoya Teirstein

Department of Housing and Urban Development

Evan Vucci / AP Photo

Scott Turner has at various points been an NFL cornerback, Texas state legislator, Baptist pastor, and motivational speaker. Little in his resume has much to do with housing, except a stint during the first Trump administration leading a White House council in charge of “opportunity zones,” or tax breaks designed to encourage investment in low-income urban neighborhoods. The effort benefited wealthy developers instead.

If confirmed, Turner will control an underappreciated instrument of American climate policy: The Department of Housing and Urban Development enforces fair housing laws and funds public housing. The nation’s massive housing shortage makes building homes — particularly affordable ones and multifamily residences in cities — a climate issue, because urban density leads to less driving and lower emissions.

Project 2025’s chapter on housing policy, written by Ben Carson, Trump’s first housing secretary, provides clues to how Turner might approach the job. It calls for repealing all of HUD’s climate change initiatives, as well as cutting funds for building affordable housing. It proposes revising zoning and building regulations to accelerate construction — but, unlike many reform efforts, it apparently does not support “upzoning,” such as allowing multifamily housing in areas previously zoned for single-family housing. If Turner follows this model, he’s unlikely to make a dent in homelessness or the climate impacts of suburban sprawl.

— Gautama Mehta

Department of the Treasury

The Department of the Treasury’s name belies its outsize importance in setting the nation’s climate agenda. Domestically, the agency that Scott Bessent would lead develops clean energy tax policy and analyzes the economic implications of climate regulation. Internationally, it represents the United States in multilateral forums dealing with climate change, like the G7, and leads negotiations on how much the U.S. will provide to poorer countries to help them adapt to a warming world.

Bessent is a hedge fund manager with an eclectic political history. He has described the Inflation Reduction Act “the doomsday machine for the deficit” and has called for increased oil production. His priorities as Treasury secretary would likely center on reducing the federal deficit, helping shepherd corporate tax cuts through Congress, and evaluating the impact of tariffs on the federal budget.

In order to reduce the deficit, Bessent has suggested that Trump should gut the clean energy tax credits included in the Inflation Reduction Act — President Biden’s signature climate legislation, which Bessent called a “doomsday machine for the budget.” He has also advised the president-elect to pursue an economic policy that includes producing an additional 3 million barrels of oil or its equivalent per day.”

— Joseph Winters

Department of State

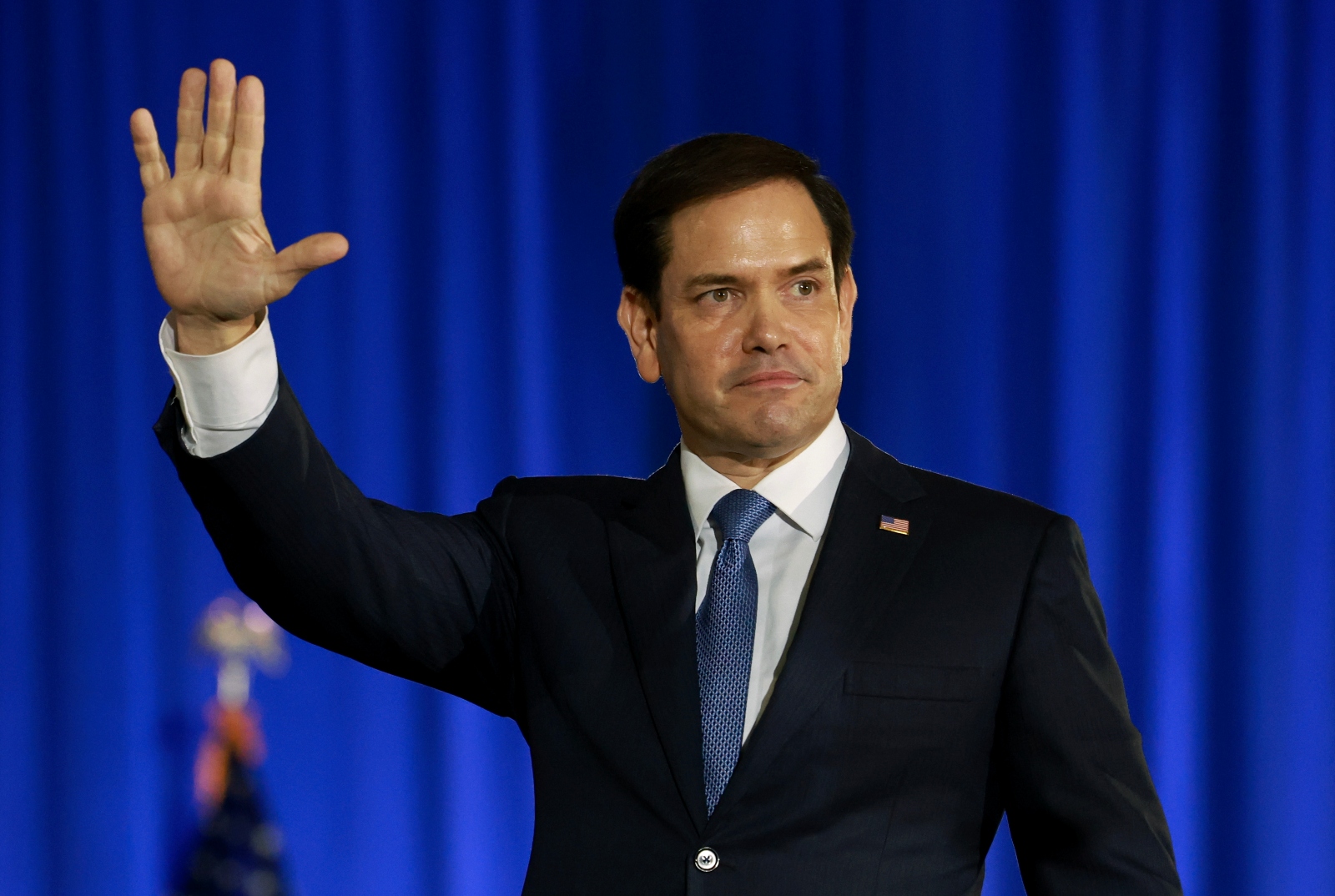

Although the nation’s top diplomat focuses primarily on statecraft, the position has under previous presidents included advancing international climate efforts through treaties, helping craft international fiscal policies to address the crisis, and using diplomatic leverage to encourage other countries to fulfill their commitments to the 2015 Paris Agreement and other accords.

Senator Marco Rubio concedes anthropogenic climate change is real — a position he seems to have come to grudgingly — but argues that aggressive measures to address it harm the economy. He favors technological fixes to emissions reduction, has called the Paris Agreement “an unfunny joke” that would “hurt economic growth,” and opposed the Inflation Reduction Act. Over the course of his career Rubio received over $700,000 from the oil and gas industry while dismissing policies that would spur the development of renewable energy.

In contrast to Trump’s isolationist America-first worldview, Rubio, who opposes a cease-fire in Gaza, often takes hawkish positions against nations like Iran and Russia. He also has received more than $600,000 from the defense industry during his congressional career. Beyond the humanitarian costs, war has a tremendous climate impact: Recent research has shown that militaries are responsible for at least 5.5 percent of the planet’s greenhouse gas emissions.

— Lylla Younes

Department of Labor

Heat is the nation’s leading weather-related cause of workplace deaths, with agriculture, construction, and delivery workers at greatest risk. With temperatures rising, the department that former lawmaker Lori Chavez-DeRemer may lead faces a growing mandate to protect those who toil in ever-hotter conditions.

The Department of Labor establishes and enforces workplace regulations and oversees the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which recently proposed the first federal heat-protection measures. Those rules have not yet been finalized.

Chavez-DeRemer, a Republican and former representative from Oregon, has supported labor-friendly legislation and is backed by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which has fought tirelessly for heat protections. (More than 20 local unions backed her unsuccessful reelection bid.) Her nomination has confounded business leaders who believed Trump would favor their interests.

During her two years in Congress, Chavez-DeRemer was among three Republicans who backed the Protecting the Right to Organize Act to make it easier for workers to unionize and engage in collective bargaining. She also pushed for a clean energy buildout in Oregon and was vice chair of the Conservative Climate Caucus. Still, it’s unclear whether she’ll support the heat rule, given Trump’s deregulatory agenda.

— Frida Garza

Department of Government Efficiency

Grist / Getty Images

This office, which President-elect Trump announced days after his election, will, he said, “dismantle government bureaucracy, slash excess regulations, cut wasteful expenditures, and restructure federal agencies.” That could profoundly hinder efforts to fight climate change.

Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy will lead this agency, known as DOGE. Although Musk acknowledges climate change is real, Ramaswamy is an “unapologetic proponent” of fossil fuels and believes “more people are dying of bad climate change policies than they are of actual climate change.” The facts prove otherwise: At a minimum, tens of thousands of people die each year from supercharged weather events.

In a recent op-ed, the men elaborated on their mission, calling out Supreme Court rulings that curb the ability of the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate power plant emissions and make it easier to challenge rules adopted by that agency and others with roles in the climate fight. “Together,” they wrote, “these cases suggest that a plethora of current federal regulations exceed the authority Congress has granted under the law.”

They also have vowed to cut the federal workforce and identify billions in budget cuts. Given Trump’s belief that climate change is a “hoax,” DOGE is likely coming for federal efforts to mitigate it.

— Matt Simon

Ambassador to the United Nations

The ambassador to the U.N. helps advance America’s climate goals by representing its positions in U.N. deliberations, advancing that body’s initiatives, and promoting solutions. Outgoing ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield, for example, has called for transitioning to clean energy sources for peacekeeping missions and championed climate-resilient agriculture.

Nominee Elise Stefanik’s position on climate change has evolved during her nine years in Congress, and her voting record is mixed. She supported the 2015 Paris Agreement and called President Trump’s decision to withdraw from it “misguided,” for instance, and she opposed opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling. But the New York Republican has since adopted more conservative views. She opposed the Inflation Reduction Act and favors market-oriented and technical solutions over regulatory efforts to address the crisis. She also endorses fossil fuel development alongside the deployment of renewables to achieve energy independence.

Stefanik, who has no foreign policy or diplomatic experience, has called the United Nations a “corrupt, defunct, and paralyzed institution,” and has pledged to advance Trump’s “America first” agenda. Coupled with the president-elect’s views on climate change and his promise to again withdraw from the Paris Agreement, Stefanik is likely to prioritize U.S. energy independence and economic interests over global climate action.

— Chuck Squatriglia

This post was originally published on December 5.