There was an important launch earlier this week where a bunch of high-profile figures came together to sign on to a new game-changing enterprise. No, I’m not talking about the gathering where Jay-Z, Beyonce, Madonna, and a dozen other artists announced their new music streaming service Tidal. I’m talking about The Next System, a project that seeks to disrupt or replace our traditional institutions for creating progressive change. Its backers include Greenpeace President Annie Leonard, clean energy champion Van Jones, United Steelworkers President Leo Gerard, climate activist (and Grist board member) Bill McKibben, and Zipcar co-founder Robin Chase, and hundreds of others.

What the Next System will actually achieve remains to be seen. For now, there’s a website and a declaration. Here’s an excerpt:

Today’s political economic system is not programmed to secure the wellbeing of people, place and planet. Instead, its priorities are corporate profits, the growth of GDP, and the projection of national power. If we are to address the manifold challenges we face in a serious way, we need to think through and then build a new political economy that takes us beyond the current system that is failing all around us. However difficult the task, however long it may take, systemic problems require systemic solutions.

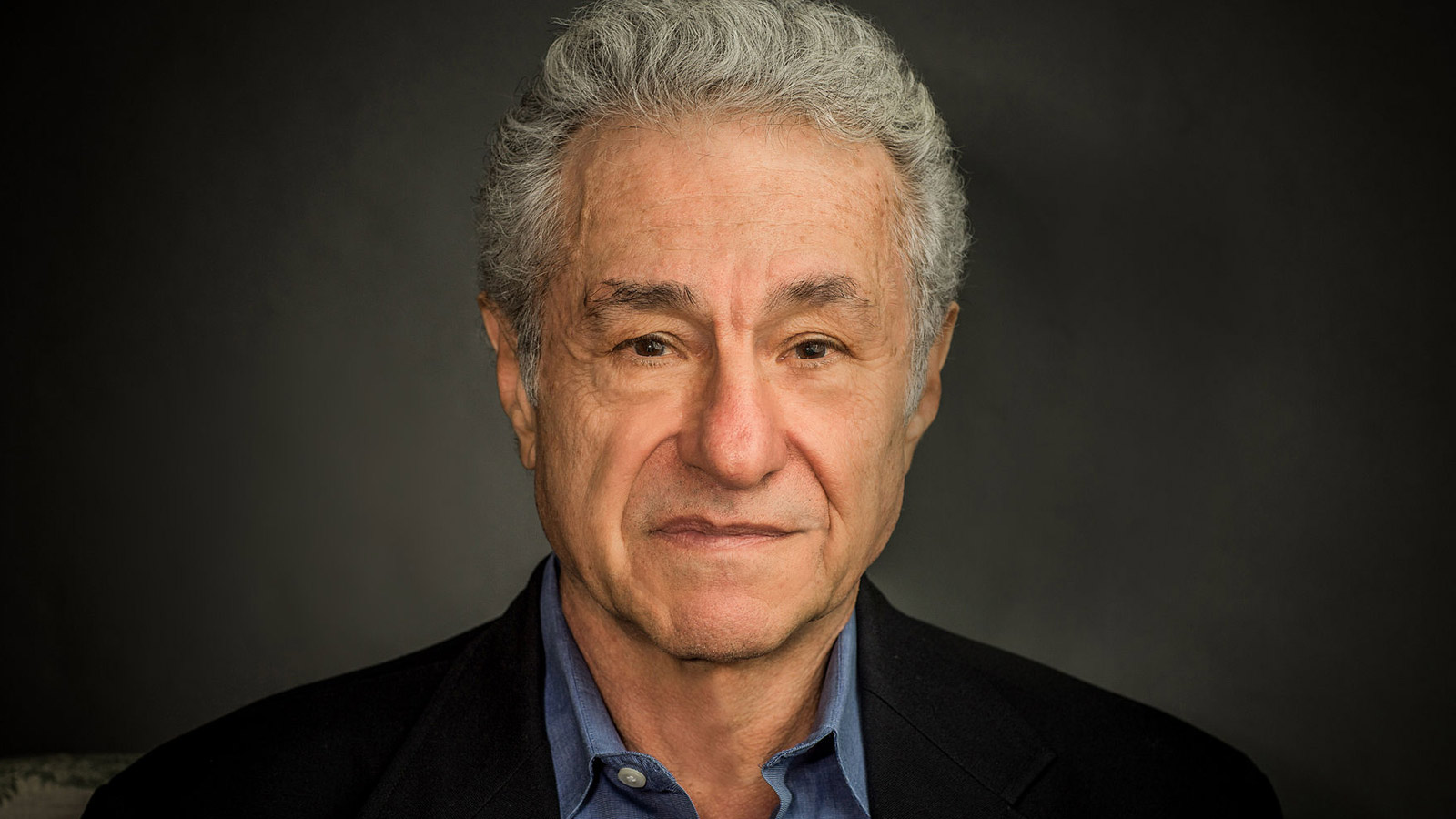

Helping head this up is the historian and political economist Gar Alperovitz, 78, former legislative aide to Sen. Gaylord Nelson, who helped spur Earth Day into reality in the late 1960s. Alperovitz was around for that and also the halcyon era of the 1960s and ’70s when Congress was able to pass effective civil rights and environmental legislation. More recently, he helped start the Democracy Collaborative, “a research center dedicated to the pursuit of democratic renewal, increased civic participation, and community revitalization.”

With the Next System, Alperovitz is hoping to shepherd discussions around what new systems and institutions can be created to help heal what political and corporate systems have desecrated. He also seeks to elevate the new systems that are already in place but could use some scaling up.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/embed/d6z4yDu3gco]One major focus of the project is on expanding business models that grant company ownership to workers. It’s actually similar to the kind of thinking behind what Jay-Z is seeking for Tidal: granting musical artists the opportunity to help generate more wealth for themselves, rather than companies, when we stream their music online. It’s a sign that people aren’t only waking up, but are also trying to do something about the fact that current business models aren’t empowering laborers.

If millionaires like Jay-Z are the wrong example for this, then consider instead what Cesar Chavez sought to achieve for farmworkers: more rights, better compensation, ownership. These are the kinds of discussions Alperovitz wants to build upon through the Next System.

“Sophisticated discussions,” though, said Alperovitz, when I met with him at his home in D.C. last month. “No slogans.”

Here’s more from our conversation on how we get the Next System moving:

Q. There are some some strong people-power movements growing right now — the People’s Climate March, Black Lives Matter, Moral Mondays — but in a post-Citizens United world, where money increasingly influences politics, are those movements enough?

A. No. If you look at the way social movements developed historically, you have to lay three or four decades on the table to see real change. They always look weak in the beginning. Right now, I’m interested in the civil rights movements of the 1930s and ’40s. It was minuscule. [African Americans during that time] said they were going to get the vote, and if they weren’t hung from a tree they were regarded as crazy by their neighbors for saying it. It takes two or three decades for that kind of social movement development, not two-to-three months or two-to-three years. So we’re currently in that kind of process. Today, there is an anger building up in different sectors, and pain and social discontent. What’s happening in Ferguson is part of it. There’s more and more anger in the environmental movement, over climate change issues. The power base always wins the first rounds.

Q. Is there any component that’s missing today that made movements effective in the ’60s and ’70s?

A. Well, the piece that we have to take seriously is the institutional question. The liberal regime that I worked in during the 1960s depended not only on the civil rights and environmental movements, but also on labor unions. Back then, they controlled 35 percent of the labor force. They had money and power and organizational strength. It was a power base and you could use that muscle to elect people. This is why [in recent years] Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker first went after the unions, and I think they’ve already won that one. What’s interesting about the new economy movement is that it’s trying to build new institutions: worker co-ops, land trusts, municipal-owned electric utilities. All of that is very primitive now, but the moral and economic pain we’re feeling can be used to drive people. But you don’t play this game without throwing at least three decades on the table.

Q. It seems like there was a much quicker turnaround after the Earth Day events, in terms of getting demonstrable results, though.

A. I think in those days, with Earth Day, we were at an explosive moment in environmentalism, and there was a liberal base who would cooperate. Today, you have things like the People’s Climate March, which is one step, but it will take a much more aggressive politics to get at these issues. The corporations woke up after Earth Day, so we’re pushing a much tougher fight.

Q. So what’s The Next System’s approach to building new institutions?

A. We’ve been working on this project for about two years. It’s an attempt to say, “Hey, we’re facing a much deeper crisis, and it’s time to talk about other alternatives.” It cannot be that the only alternatives are a declining corporate capitalism system and failed state socialism. We may be able to do better than these two things. Part of this is the new economy movement, which is beginning to develop in bits and pieces. It’s possible that nothing can be done about [the problems of] the environment, income distribution, jobs, civil liberties, and war. In virtually every one of those cases we see negative trends over the last 30 years. Only until very recently, the percentage of our population going to prison kept going up. So that means there are far deeper sources for these problems than just politics. It’s in the nature of the system.

Q. Are there any “Next System” models that exist now?

A. Yes, in Ohio. One thing we found is that universities and hospital systems purchase billions of dollars worth of goods and services every year. They’re big, big businesses. They can direct their purchasing power from A to B, meaning directly to the community. In Cleveland, we looked at Case Western Reserve University and the University Hospital system and found that none of their purchasing was coming from the neighborhoods [where the institutions are located]. A lot of that is public money — Medicaid and Medicare dollars. We’ve been working with them in an attempt to help pour [those purchasing dollars] into their surrounding community. If you set up worker ownership in that area, the profits stay there. It’s much more modeled by how you change the flow of capital and using public resources as well as private resources, but anchoring them in building the community. It’s a really significant model and I think it’s developing in certain areas around the country. [Ed Note: I’ll have more about this Cleveland model in an upcoming piece]

Q. So is there nothing to salvage or reform from our current, traditional systems for change?

A. I came out of liberal politics — that politics is over. It really is over. And it’s fundamentally over because the labor movement is over. They always fought with environmentalists, but they also elected the kind of people who would vote for environmental issues. [Sen. Nelson] was a labor lawyer. But [unionized] labor went from 34 percent of the labor force to now 6 percent of the private sector — the whole power structure is disintegrated. It’s so very hard to take a stand on any progressive issue because you don’t have an institutionalized power base anymore. Which means that corporate power is overwhelming conservative politics. People haven’t grasped how profound that change is. We’re in a systemic crisis, not a political crisis. The basic institutions of the system that supported all the things that people took for granted, they’re gone, and that’s hard for most people to grasp.

Q. Of course, with climate change, there are many who will contest that we don’t have decades to build the next system.

A. What happens when they push that argument is people think that it’s not going to happen. The trends are going to continue to get worse before they get better and there’s going to be a lot of loss. I wrote a piece recently about the number of people who are [estimated] to die [because of future climate change impacts]. We’re talking to 300,000 to 500,000 a year worldwide. As a realist, we’re going to see a lot of damage and destruction, and we’ve got to build whatever we can — a combination of adaptation and command-and-control. The conversation’s changed. It used to be, “It’s gotta be done now and if not, then the world will explode.” Now, it’s more, “You know we’re not going to get it done tomorrow, so we have to do the best we can, otherwise it’s going to get worse.”