This story is published in collaboration with Rolling Stone.

On election night in 2016, two young women drove toward a construction site off Highway 7 in northwest Iowa’s Buena Vista County. Their car contained a half dozen empty coffee canisters, several quarts of motor oil, and a pile of rags.

Throughout the previous summer, the two women — Ruby Montoya, then a 27-year-old former preschool teacher, and Jessica Reznicek, then a 35-year-old activist — had tried everything they could legally do to stop or delay the development of the 1,172-mile-long Dakota Access pipeline, or DAPL. Both women believed the pipeline would inevitably leak the crude oil it was designed to carry from North Dakota to Illinois, contaminating drinking water and soil. They’d already attended public hearings, gathered signatures for environmental impact statements, and participated in marches, rallies, boycotts, encampments, and hunger strikes. They’d even locked themselves to the backhoes that were used to excavate the pipeline. Between the two of them, they’d also logged a handful of arrests.

But all those measures failed to permanently halt construction, and by late autumn a diagonal line of pipe lay across the entire state of Iowa. Montoya and Reznicek were frustrated. While occupying a jail cell on trespassing charges following a protest in late October, they conferred with each other. Did they really, truly want this thing stopped? Was stopping the pipeline more important than their own freedom? To them, the answer was clear.

As the results of the election were being tallied, Montoya and Reznicek steered their car to the side of the road outside the town of Newell, beside a vast stubbled field that had been emptied of corn. A quarter moon illuminated the pipeline worksite before them. Montoya was nervous but focused. “You see a bulldozer, you know what it does,” she later remembered. “You know it’s not going to do a damn bit of good.”

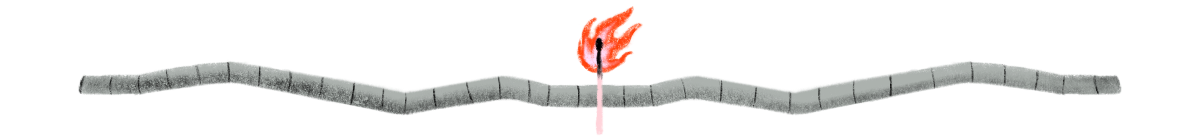

They grabbed one of the coffee cans whose tin they’d punctured with holes, stuffed it with rags, and placed it on the seat of an excavator. Then they filled the can with motor oil. They placed the other cans in the same manner in the seats of five more heavy machines parked at the worksite. Then they lit them.

Shortly after 11 p.m., a 911 caller reported seeing red and yellow flames puncturing the dark in a field off of Highway 7. By the time firefighters arrived to quell the blaze, Montoya and Reznicek were long gone. Only the charred skeletons of four excavators, a bulldozer, and a large portable crane remained on-site.

The cost of the women’s election-night sabotage was estimated at $2.5 million. Over the next six months, they taught themselves to use oxy-acetylene torches, which they used to damage four different pipeline valves in three counties across Iowa.

Often their actions went unmentioned by news outlets, although one local television station reported in March 2017 that someone had crawled under a fence and used a blow torch to melt a hole through one of the pipeline’s valves. Two months later, a radio station reported that a DAPL site in a different county had been tampered with. No suspects were named.

Despite engaging in what they dubbed a “campaign of arson” against a multi-billion-dollar infrastructure project, the women were never caught. Nor did they stop the pipeline. Oil was flowing by early May 2017. That summer, Montoya and Reznicek realized there was one more thing they could do to try to stop the project.

One day in late July, the women woke up in the Des Moines Catholic Worker House where they’d been living together since the fall. The building — one of hundreds of similar autonomous houses in the U.S., which promote a social justice interpretation of Catholicism — was a hub for the local activist community that had supported the pair’s less-clandestine efforts to fight the pipeline. Reznicek slung a backpack over her shoulder containing a hammer, a crowbar, and a statement the women had composed. Then, along with some legal advisors and friends, the pair drove to the offices of the Iowa Utilities Board, the state regulatory agency that had issued the permits allowing Energy Transfer Partners, DAPL’s developer, to run their pipeline throughout the state. When they arrived, the women stood in shin-high grass beside the building’s sign, squinting in the sunlight. Facing a crowd of about 20 people from various media agencies, as well as a Burger King across the street, Reznicek and Montoya took turns reading their statement as they elaborately described their many acts of eco-sabotage, and took full credit for carrying them out.

“Some may view these actions as violent, but be not mistaken. We acted from our hearts and never threatened human life nor personal property,” Montoya said. “What we did do was fight a private corporation that has run rampant across our country, seizing land and polluting our nation’s water supply. You may not agree with our tactics, but you can clearly see their necessity in light of the broken federal government and the corporations they represent.”

As a result of this admission, Montoya and Reznicek were indicted on nine felony charges of intentionally damaging energy infrastructure — a designation that can render a private, commercial company’s enterprise a matter of federal concern. The designation was a provision of the Patriot Act, the controversial George W. Bush-era national security law passed in the wake of 9/11, and federal prosecutors have embraced it as a way to target environmental activists who engage in property destruction.

For more than a year, Reznicek and Montoya each faced the possibility of more than a century in federal prison. Then, in February, both women entered into plea agreements with federal prosecutors to drop eight of the charges in exchange for pleading guilty to one count of conspiracy to damage an energy facility. The agreement means that the pair now face a maximum 20-year sentence each — a punishment that would still be among the longest-ever sentences for eco-activism in the U.S. The women are due to be sentenced at the end of July.

In public appearances and interviews following the indictments, Reznicek and Montoya have consistently expressed regret that they didn’t do more, sacrifice more, and destroy more property to stop the Dakota Access pipeline, which currently carries roughly 500,000 barrels of oil per day from North Dakota’s oil-rich Bakken Shale to a terminal in Illinois. A comprehensive review of the women’s voluminous public writing and speaking before and after their campaign, as well as interviews with a dozen of their friends, family, advocates, and fellow activists, paints a picture of growing spiritual hunger that found its ultimate outlet in an unwavering commitment to the single illicit objective of stopping the pipeline. (Both women have consistently declined to speak to journalists about their property destruction, given that their sentencing is still pending, but I was able to speak to Reznicek at length about other matters on the phone and during a three-day visit in January 2020.)

Though Reznicek and Montoya saw themselves as acting within the Catholic Worker tradition, their uncompromising stance on the efficacy of property destruction alienated even some within the broader movement. Nevertheless, the pair never expressed outward doubt or remorse about committing their acts, even as oil continued to flow through the pipeline.

“I am not going to choose fear,” Montoya said in 2017 to an audience of eco-activists in Minnesota, many of them old enough to be her parents or grandparents. “I’m looking at centuries in prison — and I feel more free.”

Their friendship was little more than a month old when Reznicek and Montoya got in the car to drive toward Newell. Prior to election night, neither woman had committed arson. In fact, protesting the pipeline was Montoya’s first extended encounter with activism. Reznicek, on the other hand, had already spent the better part of a decade exposed to the spiritual activist tradition of the Catholic Worker and the Plowshares movement.

The Catholic Worker Movement, which grew out of the eponymous newspaper and hospitality houses founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin in the 1930s, stressed justice and mercy and took firm stands against war, segregation, nuclear proliferation, and other forms of violence. So-called Plowshares activists follow in their footsteps. Inspired by the Biblical prophet Isaiah, who foretold of the day when nations would “beat their swords into plowshares,” these activists make personal sacrifices for the sake of a greater good, using modern-day hammers to physically and symbolically “beat” contemporary tools of war. Montoya and Reznicek saw themselves as bringing these traditional techniques to bear on the contemporary crises of climate change and water contamination.

But before all of that, Reznicek was in her mid-twenties, married to a financially secure Des Moines-area pharmacist and studying political science at nearby Simpson College. In the mid-2000s, she started on the path that would ultimately bring her to the pipeline. One week she decided, rather abruptly, to take a three-day trip to Colorado. She had no fixed itinerary — no exact destination, no hotel reservation — just an impulse to revisit a tranquil area she had enjoyed as a kid. She was looking for a way to speak one-on-one with God, she told a judge in 2016.

In place of the babbling streams she remembered, she now found brooks blocked off by “do not enter” signs. She saw large swaths of earth dug up by oil and gas industry machinery. Locals complained to her that the water could sometimes burst into flames. Instead of communing with nature, as she’d planned, she purchased poster board and markers and made protest signs to plant in front of the operation.

She returned to her home, her husband, and her studies, but things were never quite the same. “From my spiritual retreat began an activist’s quest,” she later recalled in court. In 2011, while Reznicek was in the home stretch of earning her degree, her history professor told her about Occupy Wall Street. That night she watched its live webcam until 4 a.m., riveted. She soon fished her suitcase out of storage and told her husband she was heading to New York. He warned her that their marriage would be over if she went, so she asked him to come with her. He declined, and she left to catch a bus to midtown Manhattan — “lunging into the unknown with complete enthusiasm,” she told me when we spoke by phone back in February 2020. After three weeks in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park, Reznicek learned that a satellite protest had sprung up back home in Des Moines. One of the most active occupiers in Iowa, Julie Brown, remembers precisely the moment that Reznicek arrived. It was a chilly day in November and Brown was shivering in the shadow of the state Capitol as she watched a petite blonde with pale green eyes barrel up the sidewalk to present herself. “I just got back from Zuccotti. What do you guys need?” she asked. Reznicek bought heaters and other items for the activists sleeping at the protest site, and she was soon attending every general assembly and working group meeting.

In the subsequent weeks, Reznicek and Brown befriended the Des Moines–based Catholic Workers who had volunteered to wash dishes at the camp. Reznicek noticed the Catholic Workers’ steady, constant presence at many of Occupy’s local marches, sit-ins, and rallies. Reznicek had been raised Catholic in the small town of Perry, half an hour northwest of Des Moines. Her father, who worked for the sheriff’s department, sometimes walked with her to catechism classes at the parochial school two blocks down from the stone, fortress-like St. Patrick’s church. Though Reznicek had not been a regular churchgoer since childhood, the strong social justice mission of the Catholic Worker Movement represented a way to merge her growing concerns about injustice with her desire to fill what she later said was a “nagging void” in her spiritual life.

When the Occupy movement fizzled out that winter, both Reznicek and Brown moved into one of the city’s four autonomous Catholic Worker houses. Their new home, the Rachel Corrie house, was named for an American activist who was crushed to death at age 23 as she sought to prevent an Israeli bulldozer from destroying a Palestinian home in the Gaza Strip in 2003. Reznicek began writing for Via Pacis, the Des Moines Catholic Worker newsletter, reflecting on her transition from a financially secure housewife to an activist who’d found her spiritual purpose.

“I abandoned without hesitation the routine that had strangled both my voice and my spirit. I left the house I had lived in for over five years and found my home,” she wrote. “I became liberated from the powerlessness and emptiness that accompanied the constant maintenance it required to function halfheartedly in the world of designer clothes and clammy handshakes. My decision to begin anew magnified the discontentment I had departed from and reminded me of the true meaning of my life: love and compassion.”

But Reznicek also found community life grueling, with its commitment to consensus decision-making and committee work. She struck a deal with the Catholic Workers: She would alternate stints of cooking, cleaning, and washing dishes in the nearby Bishop Dingman hospitality house with periods of going for what she called “long walks” — very, very long walks, including one from Kansas City to Guatemala (she hitchhiked part of the way), and another from Eastern Iowa to Washington, D.C.

Her sporadic voyaging was an exception that the community made to accommodate her, but it was also a practice that the house’s founder, Frank Cordaro, understood. A Plowshares activist and former priest, Cordaro often joined Reznicek on her travels. “Social justice,” he told me, “is what love looks like in public.”

All the while, Reznicek’s arrest record grew as she attended protests like the Occupy Des Moines sit-ins. In her writings in Via Pacis, she acknowledged the fleeting high that she could attain through her activism — and the increasingly perilous risks she’d take to achieve it.

“Somehow in the midst of chained wrists, cell walls, locked doors, and grieving women, beaming out from within me was a feeling of utter freedom unlike any I have ever felt before,” she wrote in 2012. “Each moment I spent at Polk County Jail, and each moment since, has generated throughout me overwhelming surges of gratitude and love (although I am mourning longingly the departure of these sentiments as my spiritual fullness reaches an inevitable period of slow deflation).”

Much of Catholic Worker activism sits firmly within the tradition of nonviolent protest, but those who identify as Plowshares activists go further. The first Plowshares action took place in 1980, a year before Reznicek’s birth, when a group of eight Catholic Workers – including two brothers who were also priests, Father Philip Berrigan and Father Daniel Berrigan – entered a facility that manufactured nuclear missile nose cones at a General Electric plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

One activist pounded two nose cones with a hammer. Then, the trespassers took out containers of their blood and poured it on some of the company’s paperwork. They prayed as they awaited arrest. When the facility’s manager arrived, the protesters handed over a document stating what they’d done and why. The activists later defended themselves in court, ultimately receiving sentences ranging from one-and-a-half to 10 years in prison. After a decade of appeals, the “Plowshares Eight” were resentenced to time served.

Since then, more than 75 such protests have taken place worldwide, according to Plowshares activist Arthur Laffin, who has also written a biography of the movement. Orchestrated by as few as one or as many as a dozen activists, each has involved symbolic property damage, self-representation in court, a sense of sacred purpose, and a refusal to hide what they did — the activists always openly took credit.

In the fall of 2015, Reznicek applied for and received a $1,000 grant to research defense contractors located in the Omaha area. She was hoping to complete the project and use the leftover funding for airfare to leave the U.S. for a quieter life where she could focus on her spiritual growth. But in the course of her research, she learned that Northrop Grumman was developing a weapons system called the RQ-4 Global Hawk — a drone that was going to be exported for use around the world.

Newly outraged, Reznicek set off for the defense contractor’s offices with a sledgehammer and a baseball bat two days after Christmas, to associate the action with the Feast of Holy Innocents. Reznicek politely introduced herself to the guard on duty, and then smashed a window and door before kneeling on the sidewalk beside her tools to await arrest.

As she sat in a cell before her trial, she told reporters, “I’ll sit in jail for as long as I need if it gets people talking.” Ultimately, she dodged a 22-year prison term and served the entirety of her eventual 72-day sentence, for trespassing and vandalism, while awaiting trial.

By the spring of 2016, Reznicek had learned about the Dakota Access pipeline. She began walking and hitchhiking to the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, the epicenter of the #NoDAPL protest. In early August, on the way north, she encountered a group of young Indigenous runners carrying staffs and feathers to Washington, D.C., to urge the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to revoke the pipeline’s permits. After spending a few days at Standing Rock, she caught up with the runners by the Mississippi River in Keokuk, Iowa, participated in a four-day ceremony, and then tagged along to Washington.

More than any other cause she had been involved in, the pipeline felt personal. The oil would be surging poisonously under her home state. She didn’t just want to call people’s attention to the pipeline — she wanted to stop it. That might take more than the symbolic actions she had engaged in so far.

That distinction between so-called direct action and other forms of protest can be murky, but typically direct action seeks to produce an immediate, specific effect: to stall or stop or make intolerably costly the objectionable endeavor. Symbolic action — protest marches, street theater, and similar efforts — reinvigorate activists themselves while targeting an injustice, with the aim of pressing public officials or other institutions to change policy.

Plowshares actions, for instance, foreground the expression of symbolic meaning. Hammering a missile head may seem like a way to render it inoperable, but the intention is more to express a possibility rather than inflict disabling damage. It’s an action “not to disarm, but to transform,” said Michele Naar-Obed, who operates a Catholic Worker house in Duluth, Minnesota, with her husband. Between them, they have participated in eight Plowshares actions. In 1993, they boarded a nuclear submarine in Newport News, Virginia, and banged on its missile launcher with a hammer and doused it in their blood. The purpose of using their own blood, Naar-Obed explained, “is so that we will not have to take the blood of anything [in war] — just the way Jesus offered his life so that others might live.”

In contrast, the radical environmental activists of Earth First!, during their heyday in the 1980s, favored techniques like planting spikes in trees to repel lumberjacks and protect old-growth forests. They advocated sabotaging heavy machinery for the purpose of actually destroying that machinery and preventing it from doing harm. Another sect of activists, the anarchic Earth Liberation Front, or ELF, likewise committed a series of strategic and sometimes spectacular acts of property destruction in the 1990s and early 2000s. Acting in anonymous cells, they set fire to buildings throughout the U.S., including an SUV dealership, a genetic engineering laboratory at Michigan State University, and — most famously — the ski resort lodge in Vail, Colorado. Though individual members attempted to maintain their anonymity in order to continue their actions, ELF regularly claimed organizational credit for its destruction through an independent press office.

The actions that Reznicek and Montoya would go on to take seem to represent a hybrid of both activist traditions, combining the severe practicality of the radical environmentalists’ direct action and the symbolic spiritualism of Plowshares actions. They would also follow the main current of both traditions by deliberately avoiding actions that might result in physical harm to people. Viewing themselves as the evolution of an established tradition, the women would later call their work a “Rolling Plowshares.”

But in the final, humid days of August 2016, little more than two months before the Newell arsons, Montoya and Reznicek hadn’t even met. With only the vaguest plan in mind, Reznicek packed a sleeping bag, a coat, some markers, and a guitar, and bummed a ride to a site two-and-a-half hours east of Des Moines where workers were beginning to bore a hole to build the DAPL underneath the Mississippi River. Her ride dropped her off just a few miles south, along a road parallel to the river. “I’m going to figure this out,” she told herself. “This is my new place.” Within moments of arriving, she located the road where trucks were accessing the site. Nearby, she found a heap of tires and plywood left over by the construction crew. She stacked the dozen or so tires to make a blockade in the middle of the road. Against it, she leaned a long wooden board upon which she’d written, in black magic marker: “Water = Life.” Then, wearing sunglasses with her hair pulled back, Reznicek stood beside the tires and played her guitar.

When a truck inside the work zone approached her barricade as it attempted to exit, she continued to play and sing. The truck shifted into reverse and backed up. Ten minutes later, Deputy Steve Sproul of the Lee County Sheriff’s Office showed up. An Associated Press photographer captured the moment: Sproul scowling at Reznicek, who’s looking back at him with a determined side-eye.

Sproul remembers roasting in his uniform as he asked Reznicek to leave. She declined, so he began to remove the tires, which Reznicek admitted she would put back after he was gone. “Should I just go ahead and arrest you now?” he asked before booking her on misdemeanor charges of interfering with official acts.

The next day, after Reznicek got out of jail, she blockaded the road again — and spent the night in jail, again. The third day, instead of facing another arrest, she disassembled her blockade and made camp on private land nearby, after receiving permission from the landowner. Then Reznicek knelt on the borrowed land and prayed for other protesters to join her. “My encampment here is just the beginning of a beautiful widespread mass movement,” she told an Iowa Public Radio reporter who caught wind of her actions. “Personal sacrifice is definitely a component of what I’m willing to risk to save our water supplies.” Within a week, 50 people showed up to join her. She called it the Mississippi Stand.

One of those arrivals pulled up in an SUV with Arizona plates. Reznicek studied the driver, a young woman with long, dark hair, as she was unloading a crisp new tent and shiny cookstove. The next morning Reznicek glanced over to see the woman practicing yoga. After an informal camp meeting, Reznicek noticed the woman’s wristwatch set to military time. One of the first things she said to the new arrival, Ruby Montoya, was: “You a cop?”

Montoya had been working as a teacher at the bilingual New Horizons Cooperative Preschool in Boulder, Colorado. She loved being greeted every day by the children, who were enthusiastic and curious. The school was the kind of place that recognized we all have something to teach each other. The closest she’d come to activism was speaking to reporters about a new law banning animals (such as baby chicks) in schools, calling it a “limiting” example of government overreach.

Then Montoya happened upon a news story describing Energy Transfer Partners’ plan to drill an enormous oil pipeline under the largest waterway on the North American continent. Concerned, she attended a local informational meeting led by Indigenous people from the Standing Rock Reservation who were calling for action. They wanted people to help protest. At that moment, Montoya felt that she had no choice but to go to Standing Rock.

To her relief and surprise, Montoya discovered that hundreds of protesters were already camped across the reservation’s vast prairie. Following the Indigenous-led #NoDAPL news site closely, Montoya read a story about a woman in a small town in Iowa who had blockaded a road with tires, and thought, “Wow, she did that by herself? That’s really cool.” Although Montoya had grown up in Phoenix, where her father is a civil rights attorney, she has roots in northwest Iowa on her maternal side. So when the article mentioned that Reznicek was out of jail and calling for people to show up to her encampment, Montoya felt summoned.

One day after Montoya’s arrival, Reznicek took her to the boring site, just beyond the camp. What she saw disturbed her: a huge blaring horizontal directional drill and remnant pools of toxic chemicals. Worse, she could smell them.

Over eight weeks, hundreds of demonstrators largely organized by Reznicek showed up for stints of varying lengths. They tried to do anything they could to slow or stop construction: blockades, even lock-ons — protesters securing themselves to construction equipment, essentially turning themselves into human padlocks, holding the equipment hostage so that it couldn’t operate without maiming or killing them. But Montoya and Reznicek grew increasingly exasperated with their lack of results.

Still, the Lee County Sheriff’s Office was overwhelmed. Deputy Sproul had never seen a lock-on before and worried about cutting through the devices because, as he put it, “you didn’t want to shear off a few digits.” They had to borrow a van to transport all the arrestees, sometimes dozens at a time.

By the end of October, Energy Transfer Partners announced that they’d finished boring under the river. Within 48 hours, the protesters were gone. The machinery disappeared soon after. “When it was over, it was like the end of the movie,” Sproul said. “The wind just stopped and the dust finally settled.”

In the days following the failure of the Mississippi Stand, Reznicek and Montoya assessed their efforts. Reflecting on the two-month direct action campaign, they realized the only time they’d accomplished something was during the lock-ons. Speaking to an audience of protesters in Iowa City, Reznicek said, “The best sound that you can hear is that machinery shutting down.”

“But you come out of jail the next day or 10 days or however many days later, and the machine’s back up and running,” she continued. “And you think, ‘This is not enough!’”

The women knew they wanted to find ways to stop construction more permanently. “Jessica and I got together and had this idea to mess with the engines of these heavy machines,” Montoya later told the publication for the radical activist group Deep Green Resistance. “We brainstormed back and forth all day,” she said, proposing and eliminating actions they weren’t sure how to accomplish, like draining the machines of their oil. “So why don’t we just burn it? OK. I know how to light a fire. You strike a match.”

Less than a month after Reznicek and Montoya’s election night arsons, outgoing President Barack Obama rescinded the permits that the Army Corps of Engineers had granted to the Dakota Access pipeline. Suddenly, it felt like the Standing Rock fight was over, and that the activists had won.

Reznicek, who was two weeks into a hunger strike at the time, welcomed the news. Her picture appeared in the Des Moines Register as she prepared to eat her first meal, a spoonful of chicken soup. However, within two weeks of assuming office in January 2017, President Donald Trump reinstated the permits. In February, Reznicek and Montoya began a road trip along the pipeline’s path in Iowa and South Dakota, using acetylene cutting torches to sever the valves at their seams, which delayed the pipeline’s construction, adding on days and weeks to its scheduled completion. “Our goal was for [Energy Transfer Partners] to exhaust their financial means,” Montoya later told the news program Democracy Now! They didn’t stop until they ran out of supplies.

As winter turned to spring, they returned to arsons — again setting fires on construction sites, resorting to the techniques they had first used in November. “Property destruction, or as I prefer to call it, property improvement, is the only solution I foresee,” Reznicek wrote in Via Pacis that April, though she didn’t admit in the piece that she’d already committed such acts. “Everything else we’ve tried, just isn’t cutting it.”

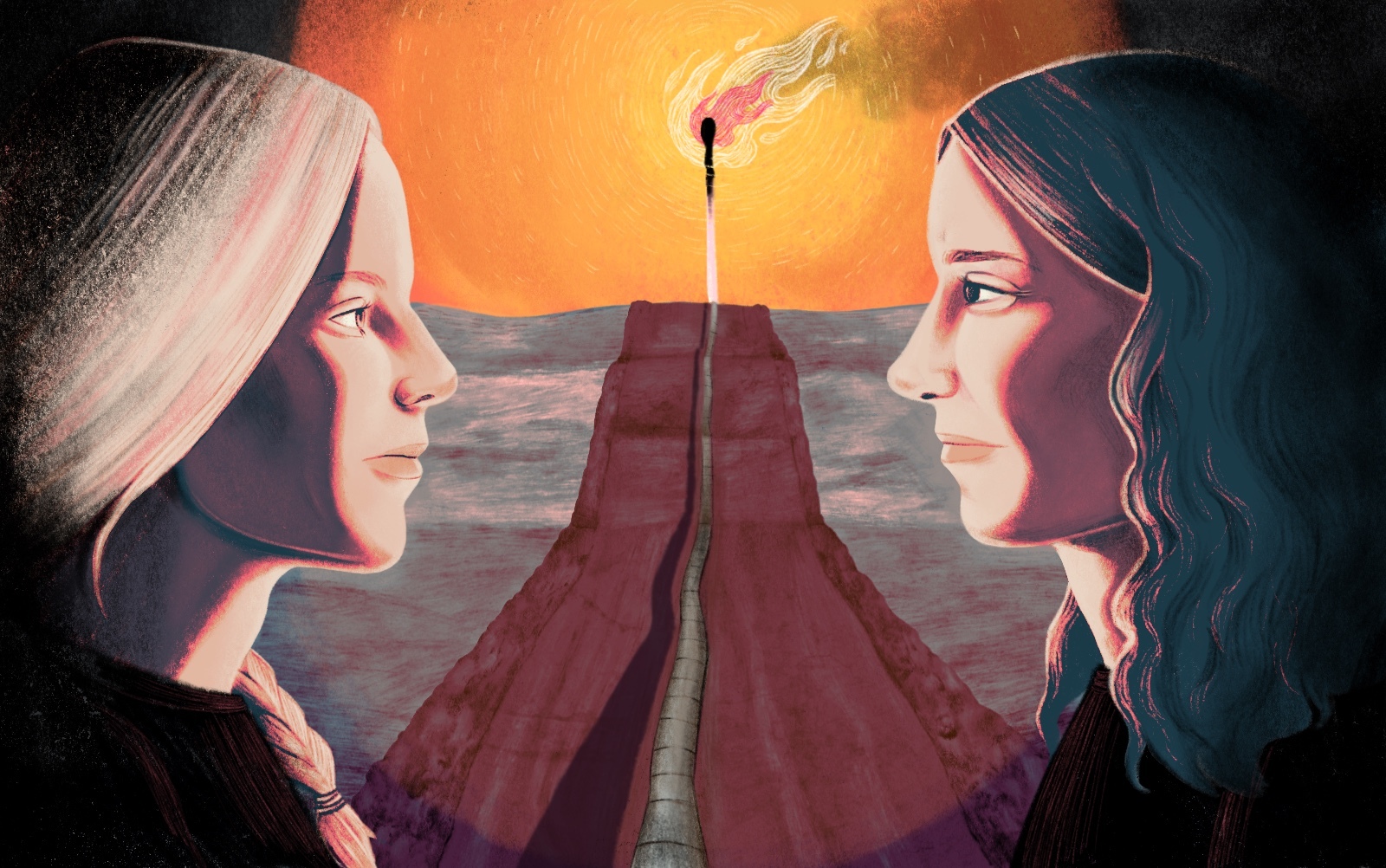

Montoya — left, holding a fellow Catholic Worker’s baby — and Reznicek appear on the cover of a 2017 issue of Via Pacis, a Catholic Worker newsletter. The issue contains the pair’s explanation for why they destroyed property related to construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Courtesy of Des Moines Catholic Worker Archives

In May, the women were attempting to blow-torch a valve in Wapello County, Iowa (not far from the house made famous in Grant Wood’s painting “American Gothic”), when they discovered that oil was already flowing through the pipeline and, horrified, backed away. They wanted to stop the operation of the pipeline, not blow it up. (They also realized that they might have blown up themselves, too.)

Reznicek and Montoya had tried everything they could think of, but the pipeline was still functioning. It looked like they were out of options. They returned to the Catholic Workers’ Berrigan House in Des Moines, where they’d been based since the conclusion of the Mississippi Stand. It was back to a life of community service, cooking, cleaning, and joining local protests for related causes. Reznicek’s article in Via Pacis that spring described her life’s work as “a slow and agonizing journey.”

In July, an investigative reporter for The Intercept reached out to the women. They agreed to speak with her, hoping that media coverage might help bring public attention back to DAPL. The publication had obtained leaked documents from TigerSwan, a private security contractor hired by Energy Transfer Partners. They indicated that Montoya and Reznicek were suspected of pipeline vandalism. The women denied any involvement.

But after the interview, they wondered whether the situation offered an opportunity. Their passion for the cause had not cooled. Although Montoya had tried to stop caring, she couldn’t let it go. She and Reznicek still felt responsible for failing to stop the pipeline. Going public with their actions presented one final opportunity to do so — “the last thing we can do,” as Montoya put it to Deep Green Resistance. After all, they had already fortified themselves for the consequences from the beginning. “[W]e were fully prepared going into it, in that mental mind game of ‘I’m driving myself to jail right now,’” Montoya later told the activist publication. If they took credit publicly, she reasoned, people might finally listen. After talking through the idea with Reznicek, Montoya concluded: “Fuck it, man, let’s claim it.”

On the morning of July 24, Reznicek woke up in Berrigan House and washed her hair, letting it air dry against her shoulders. She put her mauve Des Moines Catholic Worker T-shirt, illustrated with a drawing of people sharing a meal at a round table — the same T-shirt she wore on her first day of the Mississippi Stand. She and Montoya sat on the covered porch with their backs to the railing, and a videographer asked them how they felt about what they were about to do. Both women appeared to be holding back tears.

“I think we’re both feeling pretty nerve-wracked today,” Reznicek replied, “mainly because the oil continues to flow through the Dakota Access pipeline.”

After the interview, Reznicek changed into a plain purple T-shirt and pulled her hair back in a loose knot. Then the women, who had met less than a year earlier, set out for the Iowa Utilities Board.

After delivering their statement, standing in the grass by the agency’s sign, Reznicek extracted a hammer and crowbar from her backpack and handed the hammer to Montoya. They turned to face the sign and engaged in one last act of dissent against the agency’s authority. Montoya pried off the letter “A” while Reznicek worked on the “S,” but state troopers quickly yanked them away and handcuffed them. A reporter ran alongside Reznicek as she was being shepherded to a squad car and asked, “Worth going to prison for?” Reznicek stared straight ahead, her jaw set. “Absolutely,” she replied.

The women hadn’t been charged for actions detailed in their credit claim (only for defacing the IUB sign), but they had assembled pro bono legal counsel. Then around 6 a.m. on August 11, the FBI raided Berrigan House with a warrant to search for financial records, clothing, footwear, mobile phones, computers, tools capable of cutting metal, potential fire accelerants, literature pertaining to environmental extremism, and pipeline maps. Roughly 30 officers — local law enforcement led by FBI agents — searched the house, confining Montoya, Reznicek, and Frank Cordaro, still dressed in their scant summer nightclothes, to the porch. After four hours, the officers left with 20 sealed boxes and bags full of material, including legal notes the women had been making in consultation with their attorneys. They made no arrests.

Later that month, one of their lawyers sent an email to Des Moines’ Assistant United States Attorney, Jason T. Griess, saying that the women were “absolutely willing to surrender themselves to you or any person that you designate at your office whenever your office is ready to invite prosecution against them.” Griess responded the next day with one word: “Received.”

Still, no charges followed. So the women continued to go about their lives, which included giving talks about their activism to local audiences throughout the Midwest. At the end of September, they left a talk in Minnesota for a speaking engagement on the West Coast, but they never showed up at their destination. They stopped responding to calls and texts from loved ones. Reznicek’s father went as far as filing a missing persons report.

After about a month, both Cordaro and Reznicek’s parents received letters from the women explaining that they had uprooted their lives because they had “too much spiritual work to do,” Cordaro recalled. Thanksgiving and Christmas came and went, and the absence of the two in the Berrigan house weighed on him. “Personally my heart is broken,” Cordaro wrote in a Via Pacis newsletter. He saw the women as the embodiment of the promise of the Plowshares movement, and he worried for their future.

The Catholic Worker community was far from unanimous in its support of Reznicek and Montoya. Members debated the women’s acts in chapter newsletters for months. Some defended them, likening their property destruction to another of the Berrigans’ legendary actions, the burning of Vietnam draft documents in 1968. Others were uneasy with their destruction of property because it was “actual, not symbolic” and therefore not aligned with the Catholic Workers’ principles of nonviolence.

In January 2019, Montoya appended a personal plea onto the Catholic Worker House’s annual fundraising appeal letter, claiming that a private security contractor involved with the pipeline had been attempting to stalk and harass her, that she was suffering the “psychological and emotional effects of state and corporate repression,” and that the possibility of criminal charges haunted her. She hoped to raise funds to visit her parents in Phoenix for the first time in the momentous two-and-a-half years since “stepping into the arena” to, as she put it, “kill the black snake.”

The two women then opted to go their separate ways. Montoya returned to Arizona to work as a schoolteacher. Reznicek, who had unsuccessfully vowed in years past to turn her spiritual attention inward and away from activism, finally committed to this change of course, becoming a monastic intern at the St. Scholastica Monastery in Duluth, Minnesota. Both women were still laying low in September 2019, when a grand jury convened in Des Moines and approved charges against them.

The women’s lawyers couldn’t fathom why Griess had neglected to bring charges for more than two years. “Many think it was because the government was trying to figure out how to charge additional people, but ultimately they were unable to link them to anyone else,” Bill Quigley, one of their attorneys, said. (Griess did not reply to requests for comment.)

By October, Montoya and Reznicek had been located, arrested, indicted, released to limited house arrest, fitted with ankle monitors, and forbidden to communicate with each other. They both peacefully submitted to their arrests. They were permitted to be at work, church, or home. Each woman faced nine identical federal felony charges pertaining to illegal uses of fire and intentional damage of energy infrastructure.

The indictment enumerates precisely the acts the women detailed in the written confession they’d come forward with in the summer of 2017. However, while they described taking action “lovingly” and “peacefully,” the federal government substituted “willfully and knowingly.” The charges carried a mandatory minimum sentence of 30 years and a maximum of 110 years, plus hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines.

In March 2020, a federal judge ordered a full environmental impact review of the Dakota Access pipeline in South Dakota, siding with members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe who sued Energy Transfer Partners, citing the possible contamination of their drinking water and sacred lands. The judge stated that the Army Corps of Engineers’ initial environmental review had been inadequate and failed to respond to Sioux concerns. Energy Transfer Partners insists that its pipeline poses absolutely no threat to groundwater. Despite the Standing Rock Sioux’s arguments that DAPL should be forced to shut down while the Corps undertakes a new environmental review, which will conclude next year, a federal court ruled in mid-May that oil could continue to flow through the pipeline.

Interrupting the transport of crude oil even temporarily would likely cost the company far more than Reznicek and Montoya’s campaign of arson. Stop Fossil Fuels, or SFF, an anonymous collective whose mission includes “researching and disseminating effective strategies and tactics to halt fossil fuel combustion as fast as possible,” analyzed the women’s acts of sabotage and calculated that they inflicted about $6 million in damage by stopping about 30 million barrels of oil that otherwise would have flowed freely. “That’s less than one sixth of one percent of the $3.78 billion pipeline budget — amounting to a rounding error, and likely reimbursed by insurance,” SFF asserted.

But from another vantage point, the women were efficient in achieving their goals. In terms of barrels of oil stopped per person per month, SFF claimed that Montoya and Reznicek were “1000 times more” effective than the entire #NoDAPL campaign. By a more brutal calculus, each of them initially faced as many as 55 years in prison for every month they delayed the pipeline.

However, while the women had a worldly motivation for their actions, they also had a spiritual one. In the latter realm, their accomplishments are immeasurable, unquantifiable, and mysterious. Plowshares activists pray to become the hands of God; as such, the outcomes of their works are less relevant than their commitment to them.

“We must be prepared to accept seeming failure,” Dorothy Day once wrote, “for sacrifice and suffering are part of the Christian Life. Success, as the world determines it, is not the final criterion for judgments.” Julie Brown, who joined the Catholic Worker Movement after her experience with Reznicek in Occupy Des Moines, invoked this passage to defend Reznicek in an online Catholic Worker forum.

When I visited Reznicek at the Catholic Worker house where she was living in Duluth, Minnesota, in January 2020, she rose before 6 a.m., made coffee, and hurried out of the house to walk to morning prayers with the nuns at St. Scholastica, which is just a few miles uphill. In the early afternoon she had a shift cooking dinner for a dozen children at the Damiano Center, a nonprofit emergency meal provider. Reznicek told me she was lonely. The nuns she prayed with in the mornings were twice her age, and the kids she served in the evenings were half as old as her. Besides that, her ankle monitor limited her movement to a strict schedule. She longed for friends she could relate to, and struck up a conversation with a librarian on the church campus. Reznicek had often seen a lone fox making its way across the campus, and she wanted to know if anyone else had seen it, too.

The services at St. Scholastica helped her cope with the waves of fear and uncertainty she occasionally felt as her court date approached. As she walked home from mass in Duluth’s stinging-cold air, there was one thing in the future that she was sure about: If the feds allowed her to take off her ankle monitor, she knew exactly what she wanted to do. She wanted to head a few miles south of the Iowa classroom where her professor first mentioned Occupy Wall Street, arriving at the unspoiled shores of Lake Ahquabi. She’d take in the geese, the conifers, and the serene blue of the water’s surface — and then, without further pause, dive right in.