Hello, and welcome to this week’s edition of Record High. I’m Zoya Teirstein, and today, we’re looking at why the United States undercounts heat-related deaths.

Every week between May and October, the Maricopa County Department of Public Health in Arizona releases a heat morbidity report. The most recent counted 180 people who have died from heat-associated illness in the county this year so far. But in the course of reporting on the topic this week, I found out most people agree that that number is off.

If previous years are any indication, the true number of heat-related deaths in Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix, is much higher: At the end of last summer, the county revised its initial reports upwards by a factor of five, ultimately reporting a sobering 425 heat-related deaths in total.

“The system of death surveillance wasn’t designed for a climate-changed world.”

— Robbie Parks, Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health

Nick Staab, a medical epidemiologist for the Maricopa County Department of Public Health, works in the department responsible for compiling the county’s weekly mortality reports. His office is sent cases in which the county’s medical examiner or Department of Vital Records, the office that documents deaths, marriages, divorces, and other life events, has identified heat as a primary or secondary cause of death. Then, he and the other epidemiologists determine what factors contributed to that death. They look at where the death occurred, whether there was air conditioning present, if substance use played a role, and other risk factors.

But undercounting is likely baked into the system even before Staab and his colleagues begin their painstaking work: Any one individual along that reporting chain, from the doctor declaring the cause of death to the medical examiner writing the death certificate, might overlook heat as a contributing factor.

“It’s imperfect,” Staab said. “It relies on human reporting.” In some cases, a provider will make their best educated guess as to the cause of death. If there are comorbidities — heart disease, obesity, mental illness — heat might not make it on the list, and Staab’s office will never see the death certificate to add to the county’s tally of heat-associated deaths.

“When you have something like heat-related kidney disease or heat-related heart attack,” said John Balbus, the acting director of the federal Department of Human and Health Service’s Office of Climate Change and Health Equity, “there’s no reliable way that every doctor is going to think about it in the same way.”

Collecting data on heat-related deaths gets even trickier when you zoom out. Counties with fewer resources, limited know-how, and infrequent exposure to extreme heat events are ill-equipped to record data on climate-related illness and morbidities, let alone report them to the federal government.

But there are ways to harness data to change the status quo.

Last month, the federal government unveiled a new national dashboard aimed at improving how public health officials track heat-related illness. The tracker, modeled after an opioid overdose tool deployed by the Biden administration in 2022, seeks to provide more complete data on heat-related illness across the nation by mapping emergency medical services, or EMS, activity. The online dashboard, run by the Department of Health and Human Services in collaboration with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, tracks heat-related EMS activations — that is, calls to 911.

The tracker is an example of how data can help the government visualize trends across the whole country and deploy resources to the areas where EMS activations are most concentrated.

“This is another innovative use of data to show where people succumb, as opposed to tracking it from the emergency room,” Balbus said. Read the full story here.

By the numbers

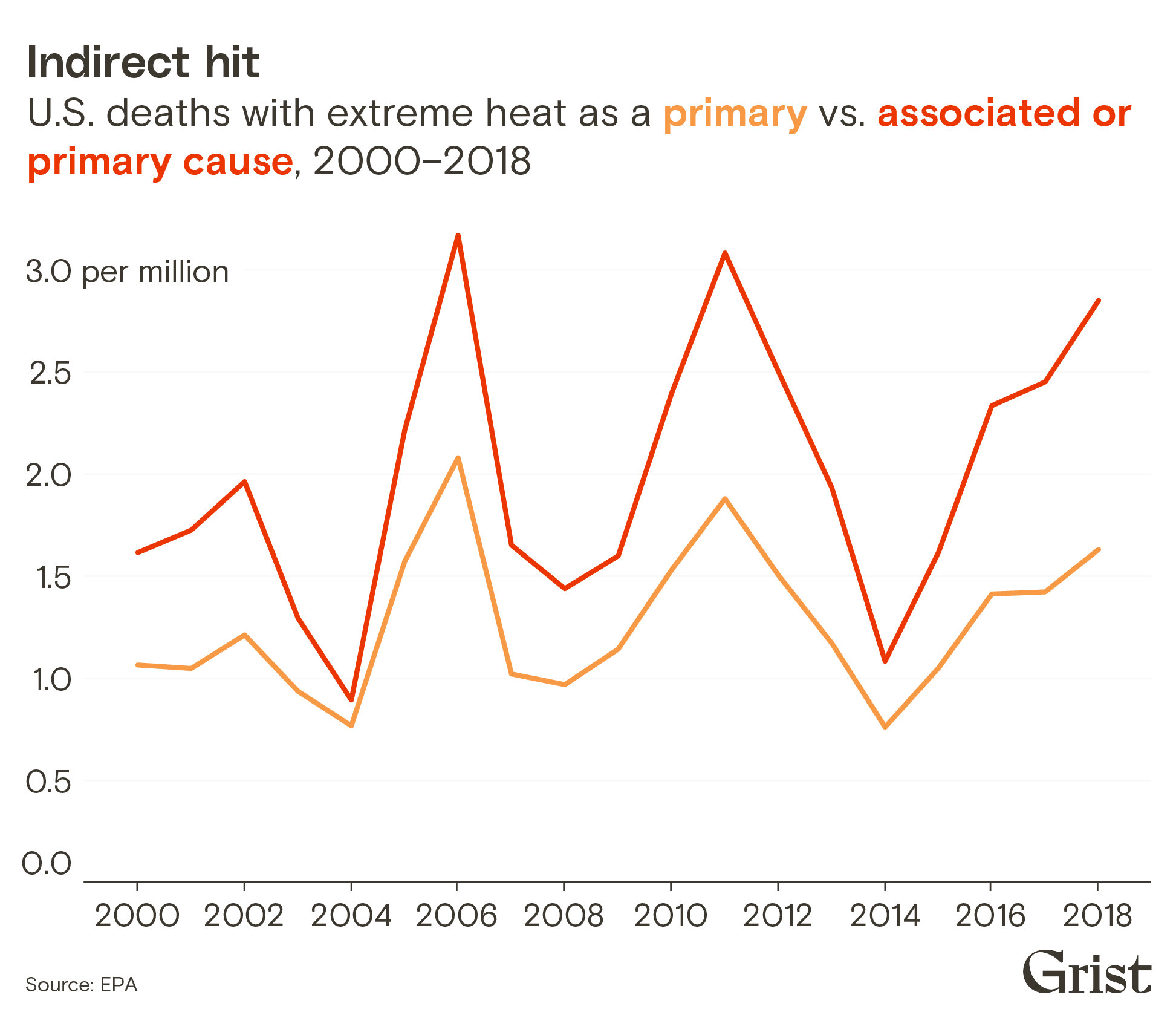

A gap in reporting exists between deaths directly attributed to heat exposure and those in which heat was listed as either the direct or indirect cause.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

What we’re reading

Citrus squeezes into the Peach State: A new citrus industry in Georgia is growing rapidly, thanks to a changing climate that makes the fruits easier to grow. As my colleague Emily Jones reports for Grist, there were very few citrus trees in the state a decade ago — now, there are more than 500,000 trees across nearly 4,000 acres.

Even the bayous of Louisiana are now threatened by wildfires: Record-breaking heat and dryness across Louisiana have helped ignite a spate of wildfires across the state. In an average year, wildfires burn roughly 8,000 acres in Louisiana; fires in August alone have set alight more than 60,000. Lylla Younes reports for Grist.

Heat is eroding shade in Nevada: Southern Nevada is at risk of losing its limited tree-cover to extreme heat, a loss that would further expose communities to climate change-fueled extreme temperatures “in one of the fastest-warming metros in the nation,” Jeniffer Solis writes in the Nevada Current.

Extreme heat is making working in Asia’s factories unbearable: We know it’s dangerous to work outside in extreme heat, but experts who spoke to the Washington Post say indoor laborers in Southeast Asia’s manufacturing hubs are also being imperiled by high humidity and scorching temperatures.

50 Cent postpones concert in Phoenix: The rapper was scheduled to perform at an outdoor amphitheater in Phoenix last week but canceled his show due to the intense heat, according to the Arizona Republic: “116 degrees is dangerous for everyone,” 50 Cent said in a tweet.