This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

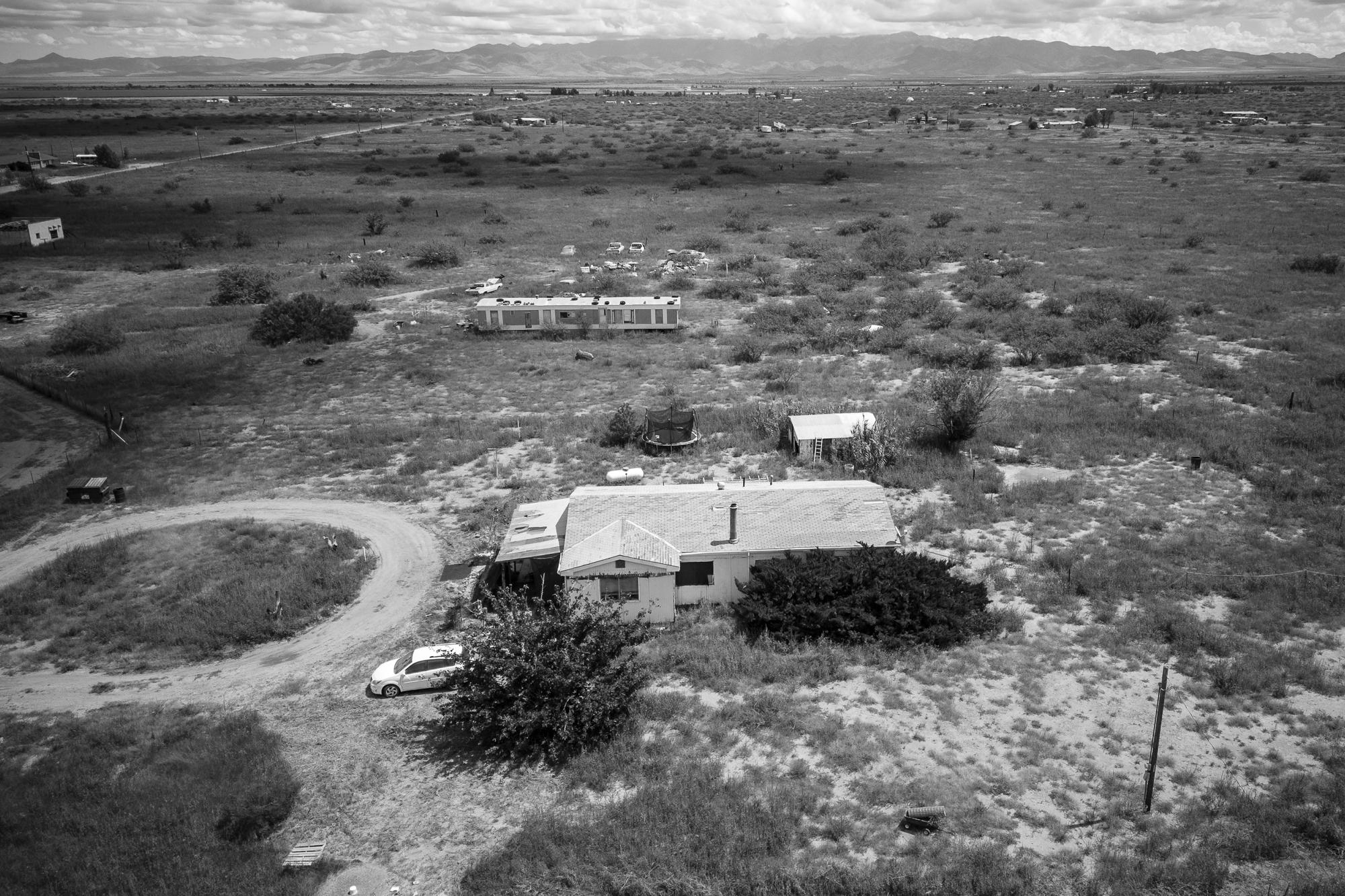

For Anje Duckels, Florida was home. Duckels, 41, was born in the Sunshine State; her family had lived there for generations. But housing prices in Fort Myers just kept rising, so she and her wife decided to find somewhere cheaper to raise their three children. Duckels volunteered to help restore a rural estate with a small farmhouse in the Willcox Basin of southeast Arizona, near the U.S.-Mexico border. After a few years in the area, they bought the property, which was located in a Cochise County neighborhood called Kansas Settlement.

Calling the Willcox Basin “remote” would be an understatement: 2,000 square miles of sand and scrub, strewn with crop fields and lined with dusty single-lane roads, it’s nothing like the subdivided coastal paradise that Duckels was used to. Most residents live at least 30 minutes from the closest store or gas station. Many live several miles from their nearest neighbor. In most of the county there are no public services or utilities. The most famous housing development in local history was a land-fraud scam that marketed empty desert tracts to gullible northerners — a sham version of snowbird refuges like the one where Duckels had grown up.

The day the family moved to Kansas Settlement, they lost their water. When Duckels turned on the faucet, she heard a spitting noise, but nothing came out. It didn’t take long to find the source of the issue: The aquifer beneath her house had dropped below the bottom of her well. The pump was pulling on dry dirt. Duckels soon learned that many of her neighbors had lost water as well, and they’d found themselves forced to haul in jugs of water on their pickup trucks or else pay thousands of dollars to drill their wells deeper.

“Not only was our well dry, but pretty much everybody in this area has a well that was dry, or going dry, or had been dry and had to be re-drilled,” Duckels told Grist.

In times of crisis, people tend to look for a villain. It didn’t take long for Duckels to find one: Surrounding her property on all sides are farms owned by a massive dairy operation called Riverview. Over the previous decade, the Minnesota-based company had gobbled up more than 50,000 acres in Cochise County to build an expansive network of farms and feedlots, according to High Country News, which has covered Riverview and the local opposition it has engendered extensively. The dairy’s wells were far deeper than the one on Duckels’ property, and she assumed the firm was sucking all the water out from beneath her.

Riverview is hardly the only reason for the area’s water crisis — the desert aquifers had never been very robust, and a climate-change-fueled drought had made the area drier than ever — but Riverview and other large farms growing nuts and alfalfa are by far the area’s largest water users. Duckels started to look at the irrigated fields around her with fear and resentment.

“That Riverview man is literally going to try to starve us out of water,” Duckels told me, referring to the Riverview board member who runs the company’s operations in the area. “I hope every single property he owns is set on fire by someone. I hope that someone salts his ground so that nothing grows.”

Cows look out from the Riverview-owned Coronado Dairy farm near Willcox, Arizona. Grist / Roberto (Bear) Guerra

A cloud of dust floats behind a hay truck passing between two Riverview-owned crops, left. Irrigation equipment, right, sprays water over the dairy’s crops. Grist / Roberto (Bear) Guerra

Duckels’ neighbors all feel the same way. The mounting water crisis has created a groundswell of anger in the Willcox Basin. Libertarian-minded locals who might once have kept to themselves have banded together against the dairy and other large nearby farms, channeling their frustration over dry wells into a political battle against big agriculture. Interviews with almost two dozen residents in the area paint a picture of a once-sleepy community that has erupted into turmoil: Residents have shown up at public meetings to shout at Riverview representatives, sparred in comment wars in local Facebook groups, and flown rogue reconnaissance flights over dairy facilities.

The growing water shortage is driving freedom-loving denizens of the Willcox Basin to a radical solution: state regulation. In two weeks, basin residents will vote on whether to establish new restrictions on large groundwater wells, the first such referendum in state history. If voters approve the new rules, it would constitute a sea change in Arizona water politics. Not only would it be one of the first times a rural community has voted to restrict its own water usage, but it would also be a rare example of rural voters succeeding in limiting the power of large-scale agriculture.

The backlash may portend a broader political shift in the arid U.S. West. Farms are by far the largest water users in the region, and rural communities from California to Texas are watching these operations suck the water from beneath their homes. Places like Cochise County have relied on agriculture as an economic anchor, but the water crisis is drawing battle lines between rural populations and the large agricultural firms that sustain them.

“Back in the day, we used to get a lot more rain, and the theme with water was: If it’s not affecting you personally, nobody’s really gonna care,” said Esteban Vasquez, a lifelong Cochise County resident who has managed local water systems. “Now that people actually see it happening, the conversation has opened. It’s something that has hit close to home.”

Unlike the sprawling Phoenix suburbs 200 miles away, Cochise County remains mostly an undeveloped desert, almost as rural today as it was when the first prospectors and miners arrived to dig for copper more than a century ago. Most residents who spoke with Grist said they moved to the area because they wanted solitude and privacy, even if that meant roughing it. In a county where the population density is a quarter of the national average, they often see more rattlesnakes than people.

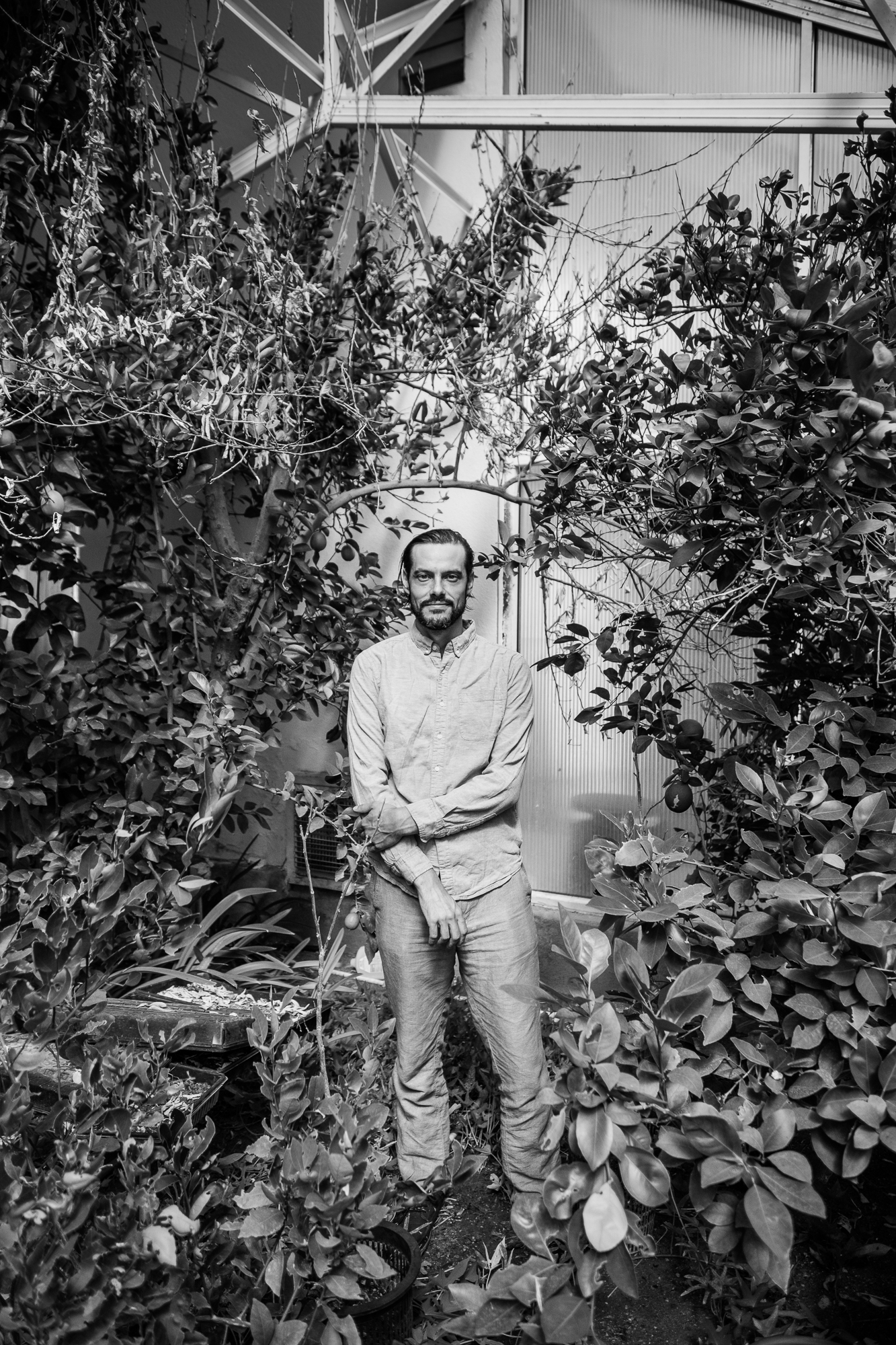

“People have to be a little bit courageous or at least ambitious,” said Christian Sawyer, who moved out to the area a few years ago in search of a quiet place where he could pursue various creative projects. “It’s people who want to do their own thing, build their own house, farm their own crops. It’s this kind of back-to-the-land libertarianism, with a bit of a hippie-type of mentality as well.”

Cochise County has a unique “opt-out” permitting system, which allows people who own more than four acres of land to build structures without having to submit to a county building inspection. This has enabled some unorthodox abodes: Some residents have built houses with composting toilets, walls made out of volcanic rock, and frames made out of straw bale.

If the absence of local regulations made Cochise County an attractive retreat for loners and libertarians, it also made it an ideal target for large farms. There have long been small cotton and alfalfa operations in the county, but over the past ten years a number of large conglomerates have moved in to grow nuts and alfalfa; several vineyards have opened as well. The growers needed a place where they could pump water with no restrictions whatsoever, and the Willcox Basin fit the bill.

These conglomerates could afford to dig groundwater wells that are much deeper than standard residential wells, giving them a de facto monopoly on the region’s aquifers. Producers have also snapped up land in unregulated localities elsewhere in the state — like the town of Kingman, where a Saudi-backed company grows alfalfa for export back to the Middle East, and Hyder, where a conglomerate called Integrated Ag has invested $90 million to grow Bermuda grass.

Riverview made the biggest splash in the Willcox Basin. Starting around 2014, the company built or bought out several separate dairy operations in the area to the tune of $180 million, beginning in Kansas Settlement and spreading out from there. With operations in five states and hundreds of thousands of cows, Riverview is one of the largest dairy firms in the country. In other states the company has been accused of muscling out family farmers by flooding local milk markets and then underpaying desperate farmers to buy them out and swallow up their acreage.

Much of the land Riverview bought had already been used for farming, but the firm dug dozens of new wells at depths of more than 1,000 feet and pumped millions of gallons of water to grow food for its large herd of heifers. State records show that Riverview owns more than 600 wells in Cochise County. The majority were drilled before the company arrived, but the wells that Riverview drilled in recent years are by far the deepest, with some of them reaching more than 2,000 feet into the earth — so deep that the water is hot from proximity to the earth’s crust. This year alone, the company has bought or drilled at least a dozen thousand-plus-foot wells.

Unlike other aquifers that are fed by rivers and streams, the aquifers in the Willcox Basin depend on rainfall alone for replenishment, so they have always been vulnerable to depletion during drought. But it wasn’t until large operations like Riverview moved in that residents started to notice their water disappearing. Groundwater accretes underground in basins, so if one user pumps a lot of water from a deep well, they can cause water to drop for other wells even several miles away. The best way to visualize this is to imagine two or three straws stuck in the same milkshake; the straw that plunges down deepest will get the last of the milkshake, even as the ones positioned higher end up coming up dry.

“The amount of groundwater pumping has increased exponentially because of what’s been happening with this dairy. And as that has happened, people’s wells have gone dry,” said Kathy Ferris, a research fellow at Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy. Ferris was one of the architects of Arizona’s landmark 1980 groundwater law, which limited underwater pumping in the state’s main population centers.

“I think we know what the problem is,” she added. “It’s not rocket science.”

A 2018 report from the state water department found that groundwater levels declined by at least 200 feet between 1940 and 2015 in the parts of the Willcox Basin with the most agricultural pumping — and that was before Riverview moved in. An Arizona water official who spoke to High Country News last year said the rate of decline has increased since the dairy arrived.

Other farming-heavy regions across the West are seeing similar stress on their aquifers from unrestricted agricultural pumping and an ongoing megadrought. California has recorded 1,287 dry well reports across the state this year, a 50 percent increase since 2021. One town in the Golden State’s Central Valley may run out of water altogether by the end of the year. The massive Ogallala Aquifer that runs from Nebraska to Texas has also shown signs of severe stress in recent years.

In the Willcox Basin, the groundwater crisis began in the immediate vicinity of Kansas Settlement, but it’s since spread out across the county as Riverview and other large farms expand farther out and draw from new sections of the aquifers that run through the county. The crisis has even started to affect the town of Willcox itself, one of the only incorporated settlements in the area, which is ten miles from Riverview’s operations. Esteban Vasquez spent five years helping manage the town’s water system, and he told Grist that even the town’s deep municipal wells were seeing stress as a result of agricultural pumping.

“There’s seriously something going on down there,” he said. “We were dropping about nine feet a year. People used to think that since we were miles away [from the dairy], that wasn’t really going to affect us and our aquifers, but it was only a matter of time.”

When Vasquez left his job with the town of Willcox and started working for a company that manages small water systems across the county, he encountered the same dry well crisis everywhere he went. According to High Country News, at least 100 wells in the basin went dry between 2014 and 2019.

The proliferation of water issues has cast a pall over the area, making life darker and more difficult for all those who live there. Everyone knows someone whose well has gone dry, or who’s had to deepen their well, or who’s taken to hauling water rather than try to find it on their own property. Many of the haulers are elderly people who live on fixed incomes and can’t afford to invest in wells, so they haul water instead, filling up jugs at a water facility in Willcox and driving them back home multiple times a week. In a county where the median household income is just 70 percent of the national figure, options for those who suddenly find themselves without water are limited.

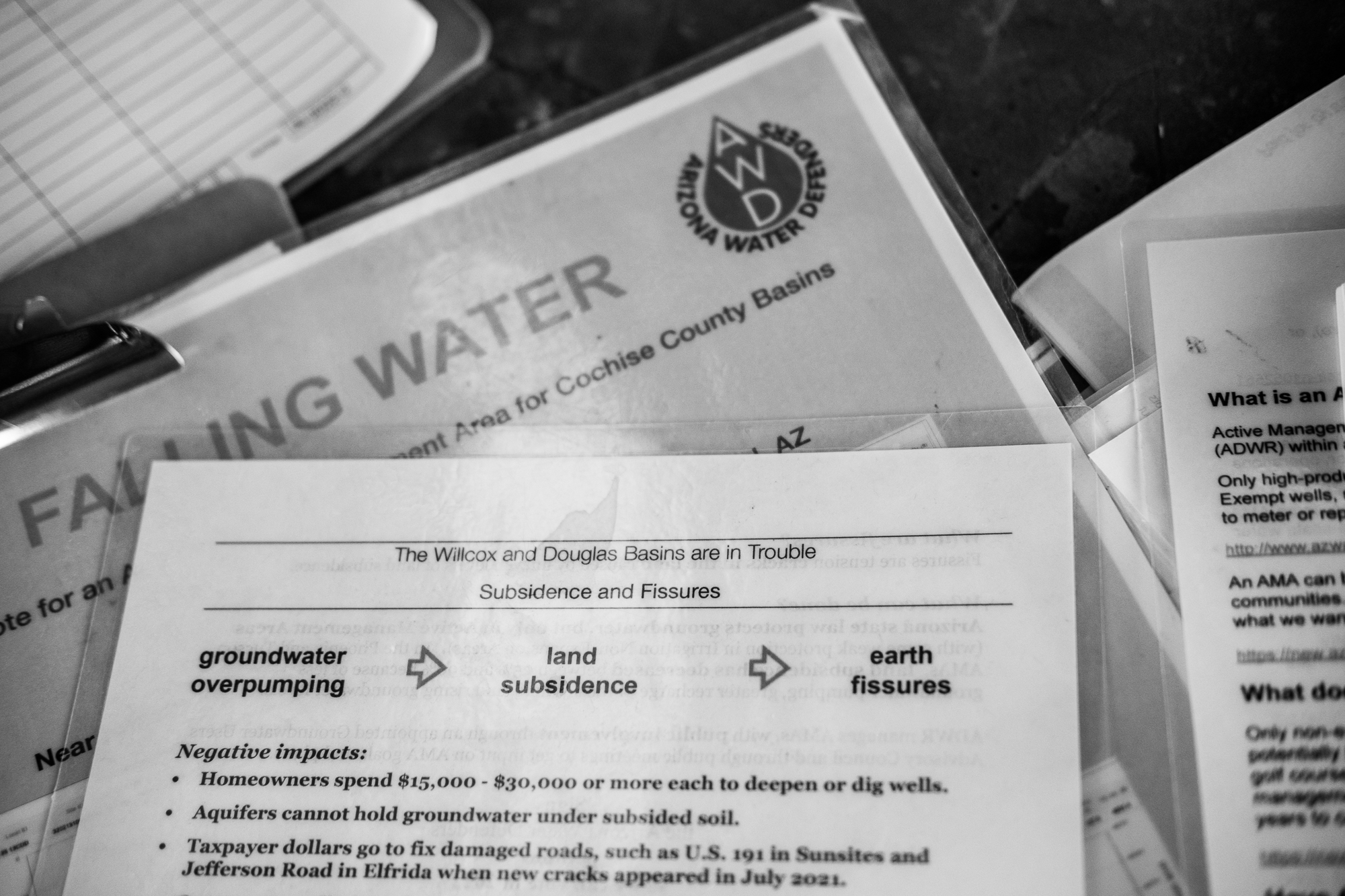

Even for those who still have water, the effects of the crisis are all too visible. In some parts of the basin, the overpumping of underground aquifers has led to the emergence of fissures in the ground that are dozens of feet deep, some of which have split apart roadways and forced local officials to close them for weeks. Dozens of people have left areas like Kansas Settlement over the past few years after losing water and finding themselves saddled with worthless properties. Vasquez said he knows at least 20 people who’ve left the county due to the recent water issues; Duckels gave a similar estimate.

Overpumping water can increase the risk of land fissures, right, a hazard noted by a sign, left, near the intersection of Dragoon and Cochise Stronghold roads near Cochise, Arizona. Grist / Eliseu Cavalcante and Roberto (Bear) Guerra

“A lot of people have abandoned their houses,” said Duckels. “You drive up and down our streets over here. You can see houses that are just decrepit, because the people have literally just had to leave their investments to rot.”

Even as the water crisis grew for years, many locals didn’t understand the scale of the problem. Because the population of the basin is so spread out, many people were not totally aware of the growth of agribusiness in the area. Opposition to megafarms was initially limited to just a few committed locals.

Julia Hamel, who lives about six miles north of the town of Willcox, was one of those people. She refers to dairy owners as “crooked bastards” and sees their expansion as part of a campaign to force out longtime residents like herself.

“These folks at the dairy have forced out families that have been there five generations,” she said of Riverview. “They can’t sell their land because no one wants it without water. Meanwhile [the dairy has] bought miles and miles of land. We’re the ones who get tromped on.”

About ten years ago, as a dairy company called Feria was expanding its operations in the Willcox Basin, Hamel and two of her friends decided to go on offense. They piloted a small plane from a nearby hangar to conduct aerial reconnaissance on Feria’s feedlots, looking out for potential health code violations. Hamel’s friends photographed large ponds she said were full of urine, as well as burning piles of manure, both of which she could smell from miles away. They tried to show the photos to local representatives, but nothing came of it. A few years later, Riverview acquired Feria. (Riverview representatives did not respond to Grist’s multiple requests for comment.)

Stunts like these were rare, but in recent years more people have come over to Hamel’s side. The local “Willcox chit chat” Facebook group has exploded with debates over how much of the responsibility for dry wells can be pinned on agriculture, with many residents blaming Riverview. Vandals have defaced some of the dairy’s signage, and residents have shown up at county meetings to berate public officials for supporting the dairy.

Anje Duckels said she’s concerned that violence will erupt in the area if water supplies continue to drop.

“You get people who see their moms cry because they’re too old to mortgage their house to pay for another well,” said Duckels. “These people are gonna get desperate and crazy. These people are frightening, they’re poor, and they’ve got weapons.”

Ironically, one major demonstration of this outrage was a pressure campaign against a proposal to actually increase local water access. In the years after Riverview arrived, a group of county politicians started to push for the creation of a municipal water district that could ease the burden on individual wells. Rather than having everyone pump water on their own property, the new district would pump water from a deep communal well and pipe it out to households.

But many residents view the proposed district with suspicion or outright hostility — not because they think it wouldn’t deliver water, but because it is supported by Riverview. Gary Fehr, a member of Riverview’s board of directors and grandson of the dairy’s founder, is one of the lead organizers behind the effort.

The water district doesn’t advertise its association with Riverview, and vice versa. But Peggy Judd, a member of the Cochise County Board of Supervisors and a supporter of the water district, told Grist the district wouldn’t have been possible without Fehr and Riverview, which she said has helped finance outreach efforts and donated office space for the endeavor.

“The power and the brainpower behind the district is the dairy, and they’re keeping it quiet. But if we didn’t have them, we wouldn’t have that gift,” she said.

As a result, many locals consider the water district part of a ploy to make the entire Willcox Basin dependent on Riverview for water access. Rumors have swirled that Fehr is laying the groundwork to build a massive new suburban development in the area: First he’ll dry out everyone’s wells, the logic goes, and then he’ll create a new water district to support the residents of his planned community.

At a series of public meetings about the water district earlier this year, numerous residents cast blame for the crisis on Riverview, suggesting the dairy couldn’t be trusted to solve a problem it had allegedly created.

“The only reason we’re here today is because our water table is going down, and the biggest single reason that water table is going down is because of agricultural pumping,” said one.

“Neighborliness is one of our values in this valley, and good neighbors don’t suck their neighbors’ wells dry,” he added to laughter and applause.

For the moment, the water district project appears to have stalled amid local opposition; the volunteer committee hasn’t held a meeting since June. Fehr did not respond to Grist’s requests for comment.

Even as residents of the Willcox Basin have spurned the dairy’s proposed water district, many have embraced a far more radical solution: strict regulations on groundwater usage. Decades of anti-regulation sentiment have given way to an unprecedented grassroots campaign for restrictions on new groundwater wells. These restrictions could jeopardize the future growth of industrial farming operations like Riverview.

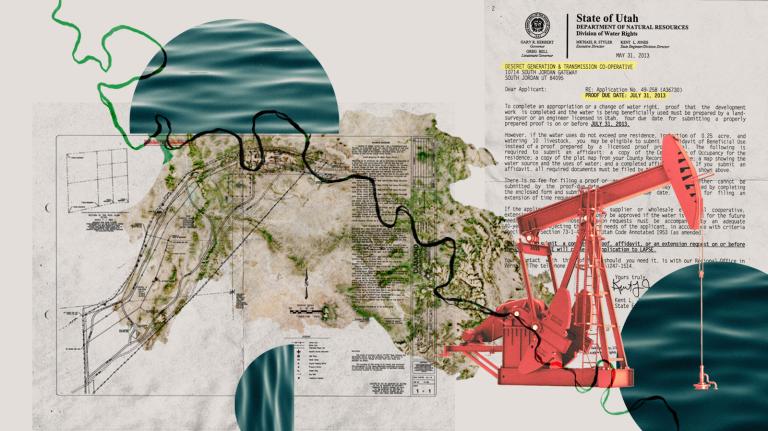

When Arizona lawmakers drafted the state’s landmark 1980 groundwater law, they were trying to solve an over-pumping problem that had begun to threaten development around the major cities of Phoenix and Tucson. Because most of the state’s population lived in these metropolitan areas, lawmakers focused on slowing new well drilling in urban rather than rural areas. The 1980 bill established so-called “active management areas,” or AMAs, in those two cities, as well as in the agriculture-heavy county that lay between them.

For four decades now, farms and large subdivisions in these areas have been subject to stringent limits on how much groundwater they can pump. Outside these three counties, however, unlimited pumping remained fair game. People in areas like Cochise County didn’t want restrictions on their water, and the potential for overdraft in many of Arizona’s more remote regions was less immediate.

“We knew that there are areas of the state where problems are worse than other areas,” said Ferris, the water expert who helped craft the law. However, “in many rural areas, they just said, ‘go away.’ They didn’t want regulation. They didn’t want us to be managing their groundwater.”

But buried within the 1980 law was a provision that allowed for the possibility that rural communities might change their mind: If residents of a groundwater basin gather enough signatures, the law allows them to propose a ballot question about whether to establish an AMA. If the ballot question wins a majority vote, the state then appoints a committee to supervise groundwater in the basin. The committee can impose restrictions on new irrigation activity, capping the amount of land in the basin that is fed by groundwater.

The proviso has never been used — until now.

In Cochise County, a local librarian and textile artist named Bekah Wilce learned about the clause a few years ago. She had started to worry about the impact of agricultural pumping on her town, Elfrida, which sits in the water basin adjacent to the Willcox Basin. Wilce’s husband, an independent journalist, started to talk with Arizona’s state water department about how large water users could be regulated. Those conversations led him to the 1980 statute, and to the clause allowing communities to form their own AMAs.

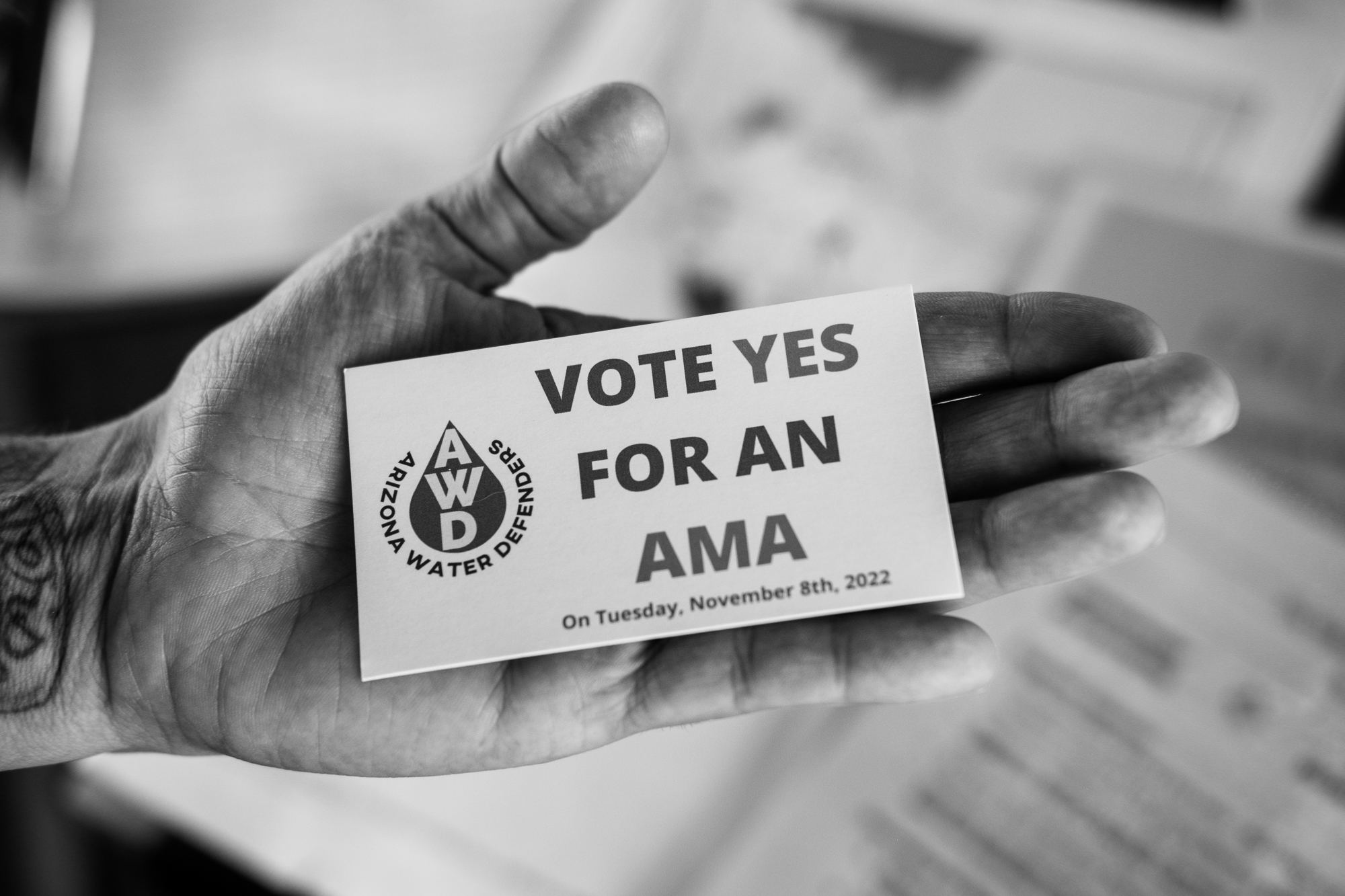

Wilce soon got involved with a group of local groundwater activists known as the Arizona Water Defenders. The group had been looking for a solution to the dry-well problem for a few years, and Wilce pitched them on gathering signatures for an AMA ballot question, something that had never been tried in Arizona before.

When Wilce first started working on the AMA campaign, her neighbors warned her that it would be a long shot. Cochise County residents tend to be quite conservative — Donald Trump carried the county by 20 points in the 2020 election — and many are averse to the very idea of regulation. So Wilce was surprised that she and her fellow volunteers had no trouble getting enough signatures. In fact, they submitted 250 more signatures than they needed to get an AMA vote on the ballot — not just in the Willcox Basin but also in the neighboring Douglas Basin, where Wilce lives. Wilce told Grist that the massive growth of big agricultural interests in the area has woken up people who might not have engaged in the past.

“It’s true that it’s a fairly conservative area — and even those on the left side of the spectrum don’t really want a lot of government interference — but I do think we see the need for common-sense limits,” she said. “The dairy has been in place now for a number of years, and people have become increasingly concerned. It’s just been this snowballing tragedy, so there’s this fear.”

The scale of support for the AMA has also surprised Vasquez, the former water systems manager, who said he’s been trying to warn locals about groundwater for years without success.

“I feel like nobody really cared about water before,” he told Grist. “Water conservation was the last thing I felt in people’s minds when it came to this community. So when the AMA got a lot of positive backing behind it, I’m thinking to myself, ‘Well, that’s crazy, because everybody that I’ve talked to beforehand didn’t give two shits about water.’”

The campaign has deepened the fault lines between farmers — including many small-scale growers unaffiliated with larger newcomers like Riverview — and the rest of the county’s residents. Now that the AMA question is on the ballot, the state has paused all new irrigation in the area until the election, freezing the growth of local agriculture. It isn’t clear how strict the AMA’s ultimate restrictions would be: Should the ballot question pass, the state will appoint a committee that will study the aquifers in the basin and decide what kinds of pumping need to be curbed. Individual households wouldn’t be subject to restrictions, since their wells are too small to meet the legal threshold for regulation, but family farmers might face limits on future growth, and they would need to go through a permitting process to drill new wells. The largest operations would likely be unable to expand at all.

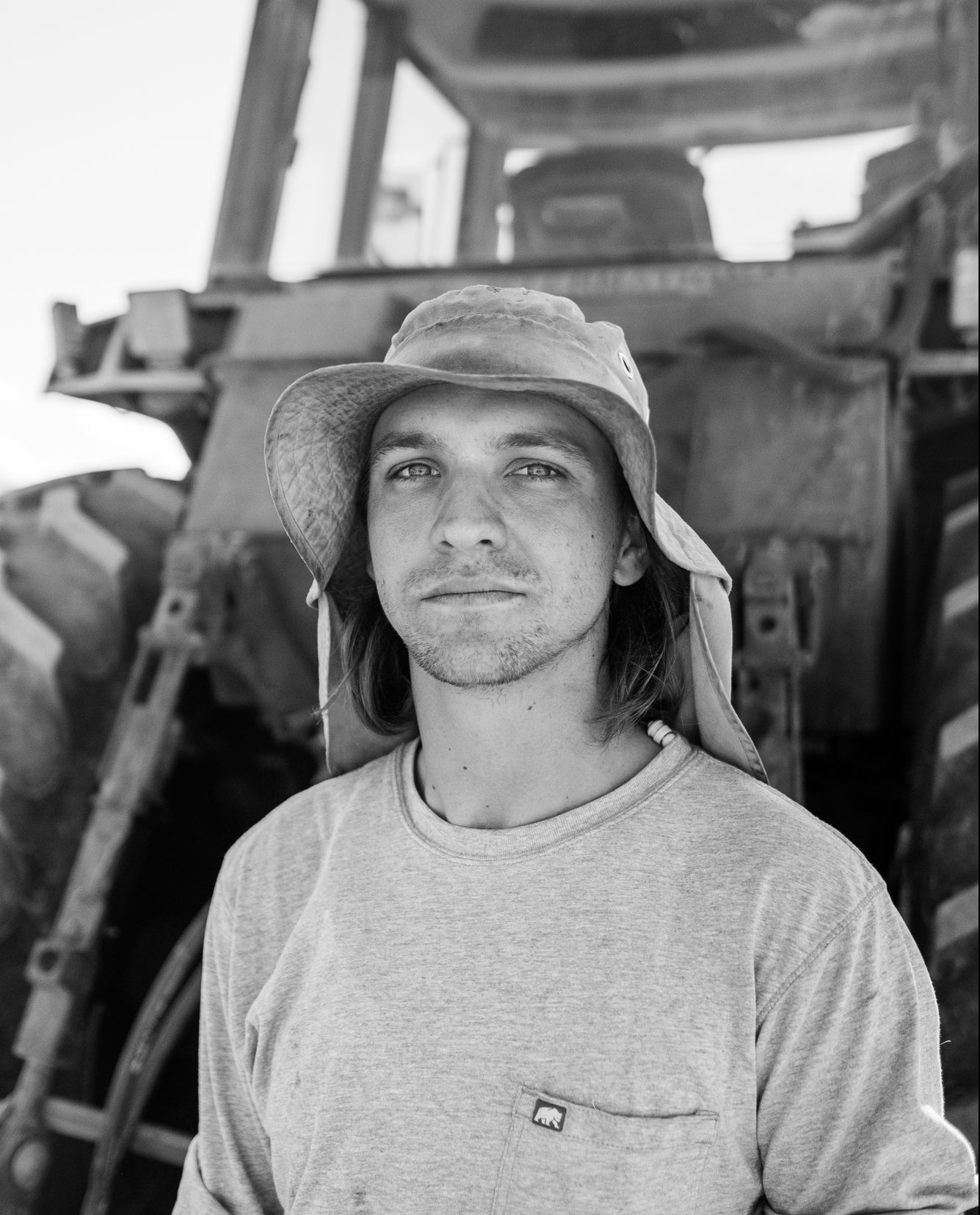

Jacob Collins, a fourth-generation alfalfa farmer who lives just southeast of the town of Willcox, said that the region’s farming community is very worried about new limitations on water usage. Collins farms about 360 acres in total, and there’s a chance an AMA might place a ceiling on the amount of land he can irrigate.

“There’s a lot of fear surrounding a loss of water in the valley, and there’s a lot of fear [about] having our water controlled by an outside entity that isn’t here,” he told Grist. “If we want the valley to continue to be farmable, we do have to do our best to make sure that we’re not using more water than we need, [but] there’s not really anything farmers can do to make a drought not happen.”

Fourth-generation alfalfa farmer Jacob Collins stands in front of a tractor on his family’s land in Arizona. Grist / Roberto (Bear) Guerra

Jacob Collins, right, drives a piece of equipment on his family’s farm, left, near Willcox, Arizona. Grist / Roberto (Bear) Guerra

These sentiments in the local farming community have led to a backlash against the pro-AMA campaign. A group called Rural Water Assurance, which was co-founded by the president of the county farm bureau, has put up billboards by the Interstate urging a ‘no’ vote on the ballot question. The Willcox Facebook group has seen a proliferation of posts warning of draconian water restrictions. Rural Water Assurance even filed a lawsuit against the Douglas Basin AMA effort in June, alleging that the signatures the group had collected were invalid. A court dismissed the lawsuit in August, finding that the plaintiffs had “wholly failed to demonstrate any legal basis” for the challenge.

Wilce feels confident the AMA vote will pass in the Willcox Basin, and a large chunk of the county’s most engaged voters seem to be on her side. If the outlook for the AMA campaign is bright, though, the outlook for the county’s groundwater is far darker, regardless of which way the vote goes next month.

Even the most stringent regulations might not save people like Duckels from having to leave the valley. At its strongest, the AMA can restrict almost all new pumping, but it can’t order current users to stop drawing water, which means Riverview would get grandfathered in. The dairy wouldn’t be able to expand its operations any further, but it could keep withdrawing water at its current rates. And the groundwater levels in the basin will likely keep dropping.

“You’re just trying to stop the hemorrhaging,” said Ferris.

The depletion of area aquifers will make life harder and harder for people like Duckels. More residents will have to haul water, or spend tens of thousands of dollars to dig new wells, or walk away from their homes and move somewhere else. In the absence of a water district like the one proposed by Riverview, there will be more new dry wells every year, and more people leaving the area. Plus, new limitations on large groundwater pumping will deter new farms and businesses from moving to the county, further sapping its already sluggish economy.

The irony, according to Ferris, is that the dairy can always move somewhere else if it loses water access. There’s a lot of land in the United States, and it’s a lot easier to move cows around than people. The absence of water regulations in the Willcox Basin has allowed Riverview to run down the clock on the area’s future, and the new political backlash against these companies is arriving too late to change that trajectory. Even if residents manage to stymie Riverview, there’s no guarantee the community will survive.

“Industrial ag moved into that basin, and industrial ag can move out of that basin. But everybody else is kind of stuck,” Ferris told Grist. “They’re living there, they invested their livelihood there, and I think the potential outlook is really grim. I think, unless something changes, it becomes a ghost town.”