This fall, the first 50 FoodCorps service members fanned out to take their posts in locations across the nation. The program — which places young leaders in limited-resource communities for a year to deliver nutrition education, build and tend school gardens, and work on bringing local food into public school cafeterias — is up against formidable odds.

In the past 30 years the percentage of overweight children has tripled and one in four young adults are not healthy enough to be eligible for military service. These statistics are only a portion of a larger more complicated picture, one where children in Arizona have a 22 percent chance of being obese, and where the average elementary school student receives just less than 3.5 hours of nutrition education per year.

Under the guidance of Debra Eschmeyer, formerly of the National Farm to School Network, King Corn‘s director Curt Ellis, and Cecily Upton, formerly of Slow Food USA, the first FoodCorps participants are already making changes in their communities. We asked three of them about their lives, their work and the road ahead.

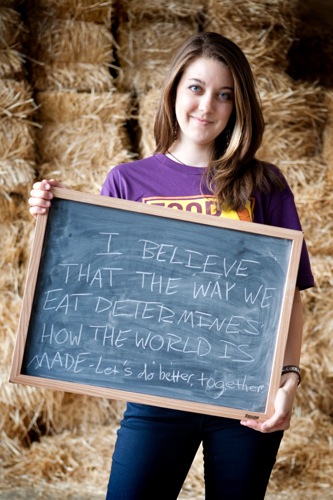

Rachel Spencer  Photo: Whitney Kidder

Photo: Whitney Kidder

Stationed at: Arkansas Delta Garden Study and Marshall High School in Little Rock, Ark.

Home Town: Fayetteville, Ga.

Age: 21

Q. Tell us about the path that brought you to FoodCorps.

A. My family members are dairy farmers, and my dad’s a hunter, so I’ve always known where food comes from, but I didn’t realize that my closeness to agriculture was so rare and special. I never thought I would have anything to do with farming. Then in college I started studying the environment and sustainability and that’s really what made it click. I studied antibiotics and agricultural production and learned that around 80 percent of the antibiotics sold in the U.S. are fed to animals for things like growth promotion — and then there are problems with antibiotic resistance. That was my food connection.

It was then that I thought, “Food connects everything.” Studying food and food issues allows you to explore policy and public health, science and education … it touches everything and everyone.

Q. What does an average day look like for you?

A. My day starts around seven in the morning, when I get to Marshall High School. I walk through the garden, watch the sunrise over the Ozarks, check on the chickens, and set out tools for the day’s classes. Then the middle school students arrive, and we learn about science, food, and health in our outdoor garden classroom.

We also make recipes with the food we harvest. On tasting days, you can find me running around the school balancing a binder with my lesson notes in one hand and a food processor in the other. Once the first bell rings, the day is a whirlwind of teaching, gardening, and cooking.

Q. What makes all this hard work worthwhile?

A. Cooking with kids and watching them try new foods that they never thought they would. We made pesto for our very first lesson and of course our kids are pretty familiar with basil, but I think out of over 200 students, only about three kids raised their hands to say they’d had pesto.

There’s something about being able to make that memory with my students. Since that first day, I’ve had something like 14 different students tell me that they’ve made pesto at home with their family and that they love it. I’ve had students come up to me and ask, “Do you have any more pesto?”

Q. What’s next for you?

A. My future was a hard question before FoodCorps, but this experience is really opening my eyes to all the options out these. It’s like it takes all of your goals and life plans and reshuffles them. I have a lot of goals, but the main one it to continue the study of our food system and to make sure that children have access to healthy food and are knowledgeable about health and how to prepare that food.

The people I admire most often don’t have job titles that are easy to articulate; they are individuals who stitch together their lives by doing what they love and tirelessly working to help others. I think that the very fact that FoodCorps exists is encouragement to dream big.

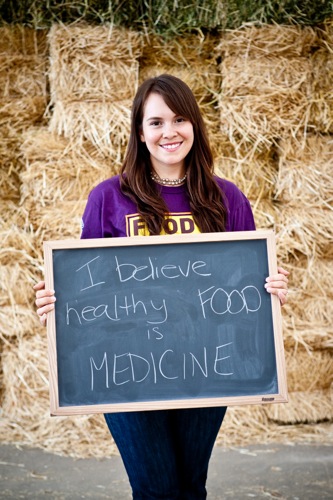

Kristi Silva

Photo: Whitney Kidder Stationed at: University of New Mexico and Farm to Table in Santa Fe, N.M.

Photo: Whitney Kidder Stationed at: University of New Mexico and Farm to Table in Santa Fe, N.M.

Home Town: Albuquerque, N.M.

Age: 31

Q. Tell us about the path that brought you to FoodCorps.

A. A lot of FoodCorps members grew up with farming families, but I didn’t. My mom was a single mom and she did the best she could. I was raised on fast food and it’s taken a long time for me to see how that affects, not just me, but my community. So it’s been a long road for me to really have my eyes opened and to see how important public health and epidemiology are. I’ve learned healthy food isn’t just a lifestyle — it’s a right.

I’ve received support in the form of scholarships (money from public and private institutions), my family, friends, mentors and advisors — and all of these resources were invested in my education. So I see my FoodCorps service as my responsibility to return an investment that was made in me, back to my community.

Q. What does an average day look like for you?

A. There is no such thing as an average day and that’s something I really love. In our small Farm to School office there are experts in areas ranging from policy and advocacy, to community outreach, to farming. We run a pretty busy schedule, with people streaming in and out of meetings all day, talking with farmers and engaging the community. I’ve spent time at the capitol building; I’ve done trainings with other FoodCorps members, spoken with senators, met with representatives.

I’ll be using my training in epidemiology to [map] the relationship between access to fresh food, poverty level, race, and obesity. We’ll be a mapping out those factors, and others, county by county, around the entire state. The [result] will be a tool, not only for researchers, but also for farmers who want to see existing routes between farms and schools or the location of existing school gardens.

There are so many different parts of the job; it’s almost like trying to keep several balloons under the water. You shove a few down and others pop up.

Every night I collapse into bed, and my mind races with lessons of the day. This project ties together all my academic training and professional experience, it’s almost like this puzzle piece that was missing that’s fallen into place.

Q. What makes all this hard work worthwhile?

A. There’s such a wide gap for the Latino and American Indian populations here. As a Latina who

grew up in that environment, I can really put faces to the numbers.

It’s one thing to learn about fancy models and frameworks in grad school, but actually applying these lessons in life to these populations and the problems at hand is another thing entirely. A long road of education has led me to a practical, tangible outcome. That’s absolutely empowering and invigorating.

Q. What’s next for you?

A. If the last month is any hint of the year, I expect to be challenged like never before.

Daniel Marbury

Photo: Whitney Kidder Stationed at: Michigan Land Use Institute in Traverse City, Mich.

Photo: Whitney Kidder Stationed at: Michigan Land Use Institute in Traverse City, Mich.

Home Town: Alpharetta, Ga.

Age: 23

Q. Tell us about the path that brought you to FoodCorps.

A. I had a position with AmeriCorps Vista, working with the Alabama Center for Economic Development, mostly in areas of tourism and folk art in rural Alabama. I worked with a nonprofit in a small town called Thomaston, Ala., trying to coordinate with performers for their annual pepper jelly festival (a jelly [they make in the area] with bell peppers or jalapenos). I saw the whole thing as a celebration of local food and food culture.

It was really my first experience in a rural community; I came to really love the cultural elements and found a lot of that fading in the rural South. I heard about the continued loss of farmland, and acres moving away from farming use all around the nation.

And [all] this comes at the same time that a lot of people are really suffering economically, in terms of jobs going away, the loss of the paper mills that once supported the town and the eroding agricultural base. I realized the disconnect between the way things are headed and where I saw the great potential in agriculture as an economic core in these areas.

Q. What does an average day look like for you?

A. I don’t really have a typical day. This afternoon I’ll be meeting with a nutrition coordinator to talk about farm to school tie-ins for National Farm to School month (October). She does all the menu design for that district so we’d like to get as much fresh and local food on the menu as we can and also have some kind of district-wide event during National School Lunch Week, which is October 10-14.

Tomorrow, I’ll be going to Frankfort Elementary and shadowing the food service staff. The goal is to roll up my sleeves and get in the kitchen and cut veggies. I [hope to] get a sense of how the kitchen flows, and what it’s like to feed 300-500 kids in a 40-minute period.

I’ll also be observing how kids move through the lunch line and maybe set up a tasting booth in a strategic location to really get a captive audience of kids waiting in line. That way I can teach them about a vegetable, or do a taste test, or something with a prize.

For the most part, I’m just shooting from the hip and running on intuition but what’s so amazing is I’m talking with and meeting with local experts all the time. I’m trying to push them to move towards local food and also trying to take in their mentorship as much as I can.

But I also get to think up zany ideas. One example is I want to have at least a few vegetable orchestra performances. There’s a group called the Trans-Acoustic Orchestra — this Austrian group that does concerts using instruments made out of veggies. We’ll be making our own veggie instruments to play with the kids.

Q. What makes all this hard work worthwhile?

A. I think it really hit me on my first day in the school cafeteria with a table full of zucchinis. We had samples of a roasted zucchini recipe and I was doing basic veggie identification. I realized that when kids have freedom to engage with food experiences — where it’s not a requirement, where it’s a choice — they take a much more active role in their food decisions. I noticed that kids already had stories and experiences of their own. Even the second and third graders would come to me saying, “My mom’s zucchini are twice that size.”

Sometimes just trying things under different circumstances makes a huge difference. I feel like I’m this ambassador, or a link in the web between all these people who are connected through food but don’t always get to talk to each other.

Being able to share the stories of food — that’s one of the most rewarding parts of the job. We’re all working to improve it, but sharing stories and connecting the community around the same goals — that makes it feel so relevant.

Q. What’s next for you?

A. I’m not sure yet. I think that I’d like to go to grad school someday for food and sustainable agriculture, or [maybe] continue my terms of service.

Interviews have been condensed and edited for length.