About 55 miles southeast of New Orleans, just before the leg of the Mississippi River splits into its three-toed foot of a delta, a crack in the river’s east bank has swollen into a massive channel. Over the past several years, it’s continued to expand, diverting more and more water from its parent river into the body of water on the other side, Quarantine Bay. Like any river, the Mississippi seeks efficiency: shorter, steeper paths to sea. That’s exactly what its new branch, known as Neptune Pass, offers.

Now, some 118,000 cubic feet of water spill through the mile-long channel every second — five times the discharge of New York’s Hudson River. It’s enough to throw off ships trying to navigate downstream, so the Army Corps of Engineers, which manages the country’s waterways, is planning to close the errant channel next month. But that, in turn, raises another problem: Sediment carried along in the river water appears to be building tiny lumps of land just off the state’s rapidly disappearing coast along the Gulf of Mexico, leading state officials to view the breach as an opportunity to harness the river’s ability to restore lost wetlands. And they are lobbying to keep the sediment flowing.

Starved of sediment, Louisiana has been slipping away, hastened by sinking land and rising seas. Wetlands are crucial for shielding the coast. They absorb the flood waters brought by powerful, climate change-fueled storms and are home to a diverse array of fish and creatures like alligators and herons. “The more wetlands we have between our communities and the Gulf of Mexico, between our communities and a hurricane that’s approaching our coast, the better off we are,” said Bren Haase, executive director of the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

The dilemma at Neptune Pass underscores the challenges of wrangling the country’s mightiest river and all the industries and people that rely on it. “It’s one of the biggest events on the river to happen in recent decades,” said Alex Kolker, a coastal scientist at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium who recently published a report on the channel. In 2016, the pass was 150 feet across; it’s since grown to 850 feet. Near its mouth, the channel courses so fast, leaping over the eroded bank, that it’s formed whitewater. “Rarely around the country are other people working with volumes of water this large,” he said.

Last year, with the pandemic keeping him at home, Kolker had “more time to geek out on the internet,” and he often spent it poring over satellite images of the Mississippi River. He honed in on one southern stretch where fissures had formed in the levee — the banks built on either side of the river — allowing water to break away and pour into the nearby bay. Kolker noticed one crevasse had quickly evolved, widening and straightening out. It seemed to be ejecting sediment into the Breton Sound, the inlet between the coast and the Gulf of Mexico, where none had been before.

Such behavior was once typical for the Mississippi, one of the main ways the river built up land, depositing sediment as it wandered across the floodplain. But the Army Corps’ 140-year-old system of levees — installed for flood control and navigation — prevents crevasses, with the exception of those that form south of Bohemia, Louisiana, on the river’s east bank, where there are no towns and the levees aren’t meticulously maintained. According to Kolker, the last 15 years of high water, fueled by heavy rainfall, could have stressed the old rock levees that line the river, leading to the formation of Neptune Pass.

The Army Corps had also been monitoring the crevasse over the last year, ready to intervene once it began to obstruct navigation. The Mississippi River is one of the country’s major arteries of industry, where ships nearly as long as the Eiffel Tower is tall sail up and down its southern stretches, many of them shuttling fossil fuels, the production of which has played an outsize role in endangering Louisiana’s coast. Trouble started brewing last month, according to Ricky Boyett, a spokesperson for the Corps. Neptune Pass had captured enough water to actually slow the Mississippi River downstream. As a result, sediment was falling out of the current and, bit by bit, rising into shoals that had never existed on that stretch of the river. “That was an indication that we’re gonna start getting major impacts,” Boyett said.

In mid-May, the Corps sent a dredge to remove the piled-up sediment. They also began hatching plans to seal the crevasse and restore the lower Mississippi’s rapid flow, which usually jets sediment straight to sea. Starting in July, the Corps will lay down a blanket of rock where the bank has washed out. But the Corps does recognize the importance of sediment’s ability to travel and build land, Boyett said. So they’re considering a barricade, farther into Neptune Pass, with a narrow opening that would allow small boats — which have been taking the shortcut into Quarantine Bay for months now — water, and sediment to keep sailing through.

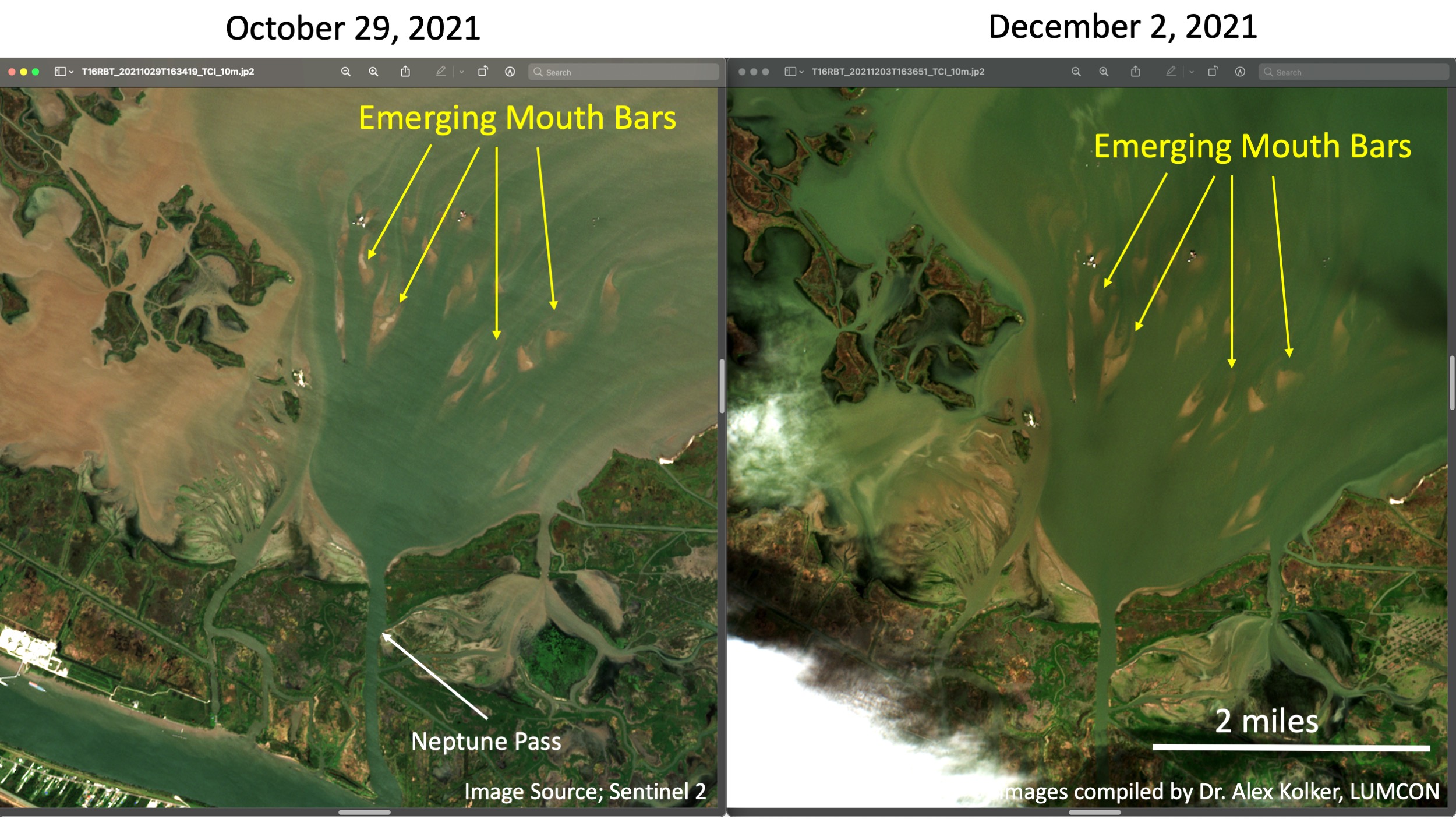

The Corps and the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority recently met to discuss the construction plans. Haase said the Corps was receptive when he recommended viewing Neptune Pass “as an opportunity — not necessarily just a problem for one facet of why we manage the river.” Signs of land-forming are already evident in satellite images: tear-shaped islands called mouth bars. Uninterrupted, they could grow into a fan-shaped blob of land over the next century or so, similar to those on either side of the small fishing town of Venice, a few miles down river.

Boyett said the Corps’ priority is maintaining navigation and commercial traffic. “But if we can do it and get benefits on the other side too, why not?” he asked.

As the Corps finalizes its plans to close the crevasse, the Mississippi River may have yet another trick up its sleeve. In early June, a few weeks after his first survey, Kolker returned to map the bottom of Neptune Pass with sonar. He was stunned to discover massive underwater holes, one of them at least 100 feet deep and 650 feet wide. Even if the Corps’ new gate allows water and sediment to stream through, the closure would likely slow the current. Kolker wondered if the current would be strong enough to flush sediment into the bay, or if that precious sand and grit would simply fall into the depths of Neptune Pass. More modeling is needed, he said, before scientists can predict the river’s next move.