Greenland’s melting ice sheet will raise global sea levels by at least 10.6 inches, twice as much as previous estimates, according to a new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change. That’s even if everyone stopped burning fossil fuels today.

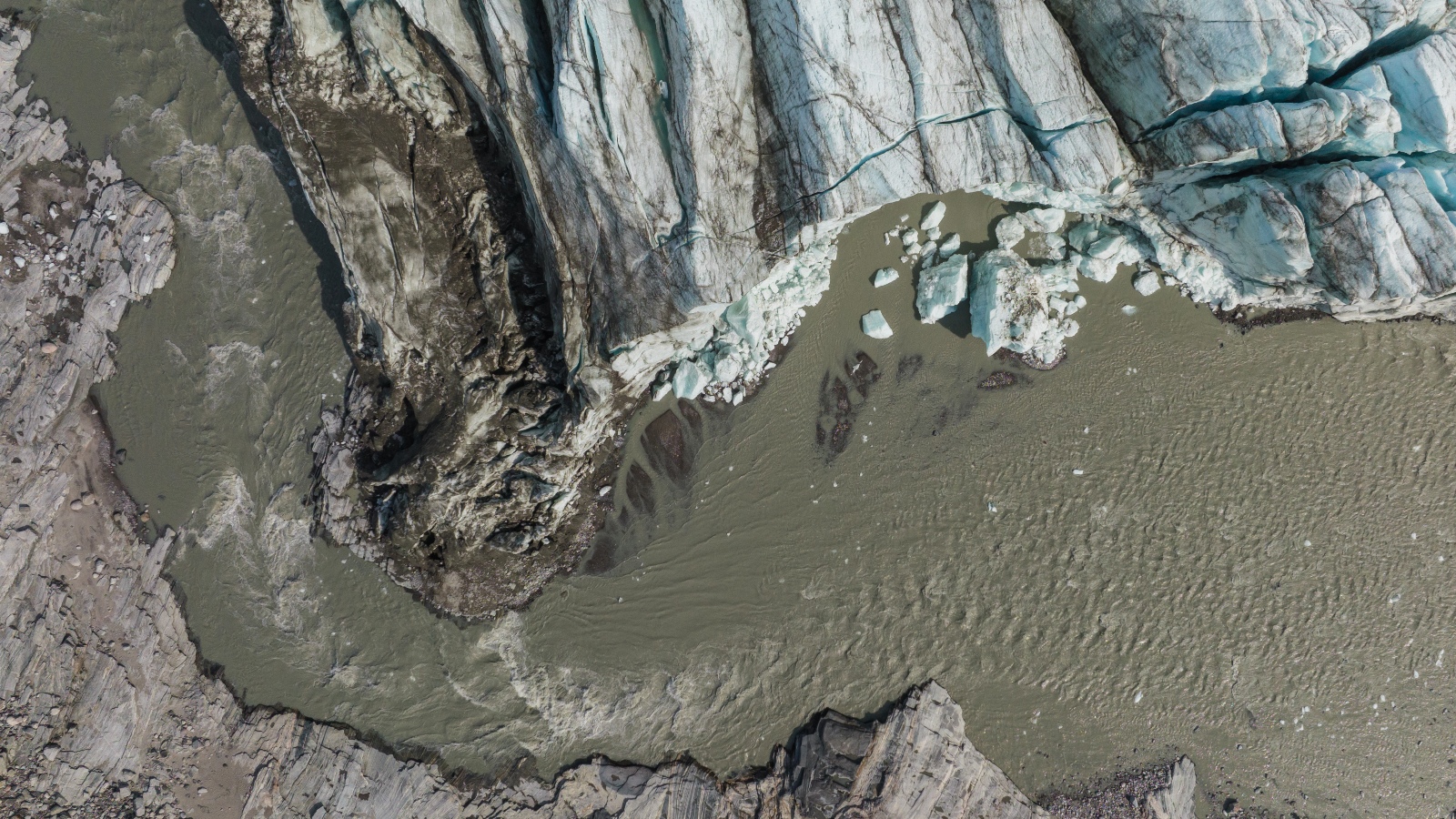

Researchers used a new method to calculate Greenland’s minimum ice melt, looking at so-called “zombie ice” that is doomed to disappear as glaciers receive less snow. The snow line in Greenland has been creeping higher as the world warms, exposing the ice on the island’s edges. Without that snow as a buffer, researchers say, this “dead ice” will inevitably thaw into the ocean, pushing up sea levels around the planet. They calculated that 110 trillion tons of ice are destined to melt, or 3.3 percent of the Greenland ice sheet.

Though the study didn’t provide an exact timeline, researchers expect that this will take place by the end of the century, or by 2150 at the latest, with consequences for coastal areas around the world.

The new research used real-world data rather than the computer models that are typically used to calculate how much — and how quickly — Greenland’s ice sheet will melt. That might explain why the projections were so much higher than previously forecast. A report last year from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a panel of the world’s top scientists, projected a two- to five-inch rise by 2100, depending on how much more carbon gets pumped into the atmosphere. The new research suggests that extreme temperatures could eventually trigger as much as 30 inches of sea-level rise.

Some glaciologists contend that previous models, though they’re complex, lack the level of detail to reflect the real-world changes that are taking place. The world has already heated up by an average of 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial temperatures, and the Arctic is warming four times faster than the global average.

“Every study has bigger numbers than the last,” William Colgan, a study co-author at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, told the Washington Post. “It’s always faster than forecast.”

This isn’t the first time that researchers have had to revise their projections based on the real-world consequences of climate change. In 2020, wildfires burned 10 million acres in the Western United States, closer to what scientists had projected for 30 years in the future. In June last year, a heat wave that broiled parts of the Pacific Northwest in 120-degree temperatures was more in line with what researchers pictured might happen later this century.

It’s not so much that climate change has been progressing faster than scientists predicted, but that scientists have sometimes underestimated the dire effects of the warming that’s already here, Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, told Grist last year.

Despite accusations of “alarmism,” the projections that come out of the peer review process usually tend to err on the side of caution. One paper from 2012 found that researchers had misjudged the risks of the potential disintegration of the West Antarctic ice sheet. So perhaps it’s not all that surprising that the danger posed by the Greenland ice sheet, too, might have been underestimated until now.