On the evening of July 14, NASA launched the Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation, or EMIT, 250 miles up to perch on the International Space Station. With the satellite’s speed in equilibrium with the Earth’s gravitational pull, the instrument took off into orbit and has been circling our planet once every 90 minutes ever since.

EMIT belongs to a category of equipment known as spaceborne imaging spectrometers and was designed to examine how flurries of airborne, mineral dust on the Earth’s surface affect temperature changes across the globe.

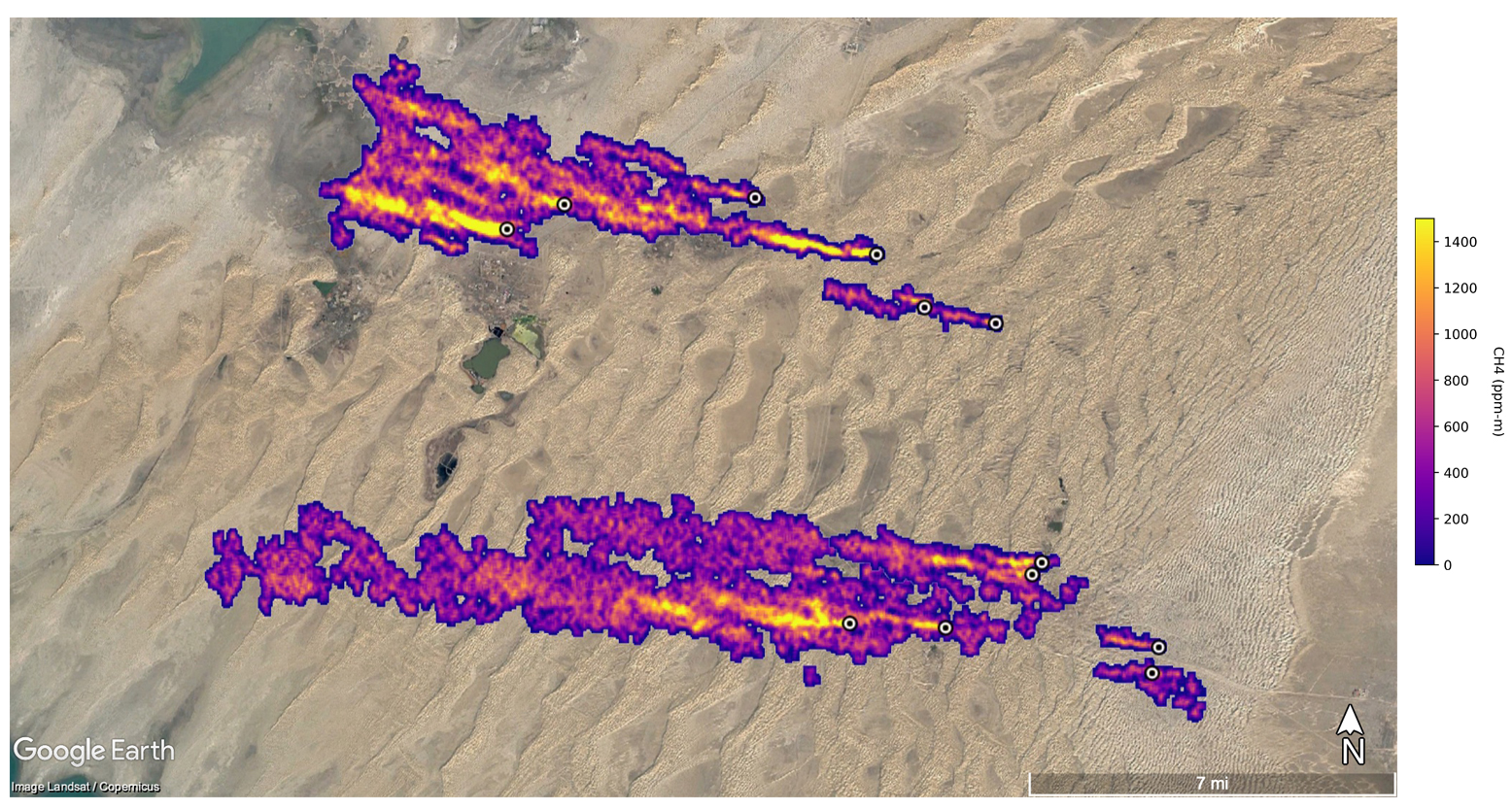

In the three and a half months following EMIT’s launch, the tool has not only successfully mapped out massive dust plumes and their effect on the changing climate, but has also identified another key piece to the global warming puzzle: more than 50 methane “super-emitters,” some of which had previously gone unseen.

Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, is a byproduct of decomposing organic material and the leading component of natural gas — the fuel used in power plants as well as in heating and cooking appliances in buildings. In the 20 years after release, methane is estimated to be 80 to 90 times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. In 2021, the amount of methane in the atmosphere soared to the highest level on record. And super-emitters — oil fields, pipelines, landfills, animal feedlots, and other facilities that emit methane at unusually high rates — are a major part of the problem. Researchers have estimated that super-emitters account for between 8 and 12 percent of all methane emissions from the oil and gas sector.

The super-emitters that EMIT identified included oil and gas infrastructure east of the port city of Hazar, Turkmenistan, emitting methane at a rate of 111,000 pounds per hour. Off of Carlsbad, New Mexico, the apparatus detected a previously unidentified 2-mile-long plume rising from the Permian Basin, one of the largest oilfields in the world. A waste-processing complex in Iran, also previously unknown to scientists, was found to emit an estimated 18,700 pounds of methane per hour.

Scientists at NASA aren’t the only ones using satellites to track methane leaks. A French geoanalytics company called Kayrros SAS uses a combination of satellite data and algorithms to identify super-emitter sites. In February, researchers from Kayrros and various climate institutions announced that they had used satellite instruments to identify more than 1,800 major releases of methane globally in 2019 and 2020.

While carbon dioxide lingers in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, methane breaks down after about a decade. Due to this timeframe of atmospheric response, a deceleration in the rate of global warming could come to fruition relatively swiftly if the world confronts its methane emissions.

Last fall, during the annual United Nations climate conference in Scotland, the United States and European Union announced the Global Methane Pledge, an international initiative aiming to slash the world’s methane emissions by 30 percent by the end of this decade. More than 100 countries have signed onto the pledge. Researchers say that slowing methane emissions can be achieved at relatively low cost — for instance, by requiring oil and gas companies to repair leaky equipment and forbidding them from intentionally venting methane into the air. Improving livestock manure management and plugging abandoned oil and gas wells are other strategies that could yield major benefits.

NASA hopes that EMIT can be part of those solutions. “Reining in methane emissions is key to limiting global warming,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement. “This exciting new development will not only help researchers better pinpoint where methane leaks are coming from, but also provide insight on how they can be addressed — quickly.”