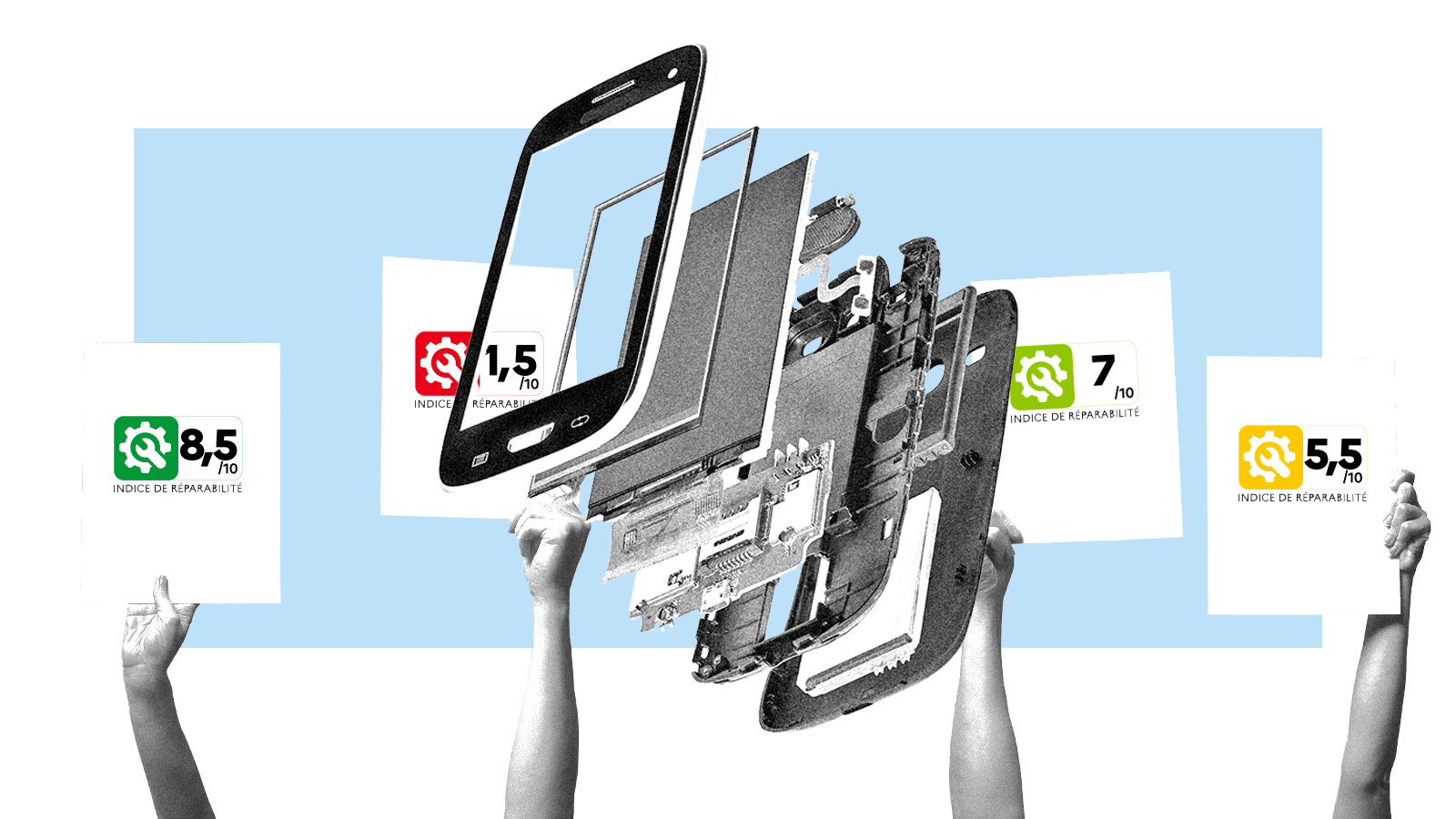

At the start of the year, the French government began requiring makers of smartphones and laptops to assign their products a “repairability” score based on how easy they are to fix — a first-of-its-kind governmental requirement with potentially global implications. Now, leading consumer technology brands including Apple, Samsung, and Microsoft have started to comply with the law by grading their products in French. And you don’t have to be a Francophone to see that the grades are, well, pretty lackluster.

Apple, the world’s most valuable consumer tech company, was unable to give any of its iPhones or MacBooks a repair score higher than 7 out of 10, making it a C student at best by the company’s own math. Competitor Microsoft, meanwhile, failed to crack 5 out of 10 for any of the products it scored, a list that includes the dual-screen Surface Duo and several Surface laptops. Samsung, the No. 1 smartphone seller in France and globally last year, also gave many of its phones failing marks. But it scored better on several devices for which it has recently made repair documentation available, highlighting companies’ ability to make their products easier to fix if they choose.

Taken together, these initial repairability scores offer a unique window into information that companies don’t tend to highlight in their yearly sustainability reports, but which has major environmental implications. The harder our devices are to repair and maintain over time, the more often we have to buy new ones that require additional energy and resources to make — and the more toxic e-waste we generate along the way.

“It’s hard to overstate the impact of seeing a device’s repair index score — a measure of how easy or hard it will be to keep the thing running well for a long time — right next to the price,” said Kevin Purdy, a writer at the repair guide site iFixit who has been following the rollout of the new French regulation closely.

France’s repairability index is a score out of 10 that manufacturers of certain consumer devices must assign to their products based on five criteria, including the availability of repair documentation, product disassembly information, and the availability of spare parts. A rating for each of the five criteria is calculated based on a worksheet that integrates numerous factors. For example, within the disassembly criterion, companies give their products a subscore for “ease of disassembly,” or how many steps it takes to remove commonly broken parts like the screen and battery, and a subscore for “accessibility,” which reflects whether proprietary manufacturer tools are needed for the repair. The criterion related to the availability of spare parts, meanwhile, includes subscores that reflect how many years screens, batteries, speakers, and other components are available to manufacturers, repair professionals, and consumers.

Companies are self-reporting these scores, a fact that has been met with some skepticism by repair advocates. But the initial trickle of repairability indexes from the consumer tech realm suggests it’s going to be hard for corporations to game the worksheet in their favor.

Apple, for instance, is generally loath to describe its products in anything less than glowing terms. But so far, Apple’s self-reported repair scores are uninspiring. The 16 iPhone models Apple has graded, from the iPhone 7 onward, received 5.5 out of 10 points on average. Generally speaking, Apple’s competitors aren’t doing much better: Google assigned its Pixel 4a and Pixel 5 smartphones a repair score of 6.3 out of 10, while Microsoft gave its Surface Duo — a kind of double smartphone sandwich — just 3.7 points.

Looking more closely at performance in the individual criteria areas, it’s possible to see where devices are losing points. Perhaps unsurprisingly, iPhones scored very poorly on “ease of disassembly,” with many models receiving fewer than 2 out of 10 points in this area. Two models, the iPhone XR and the iPhone 11 ProMax, actually got zeros here, suggesting that none of the commonly broken parts, including the screen and the battery, can be taken apart in 16 or fewer steps. MacBooks also fared poorly on ease of disassembly, averaging 2.9 out of 10 points.

Microsoft laptops, by contrast, cleaned up on ease of disassembly with an average subscore of 7.5 out of 10. But the company’s overall repair scores were tanked by the fact that its laptops received zeros for spare parts availability and pricing, indicating that out of a list of 10 parts, including the RAM and the keyboard, none are available for five or more years after the product is discontinued by the company. (Companies must give themselves a zero for spare parts pricing if any commonly broken part is unavailable.) Overall, Microsoft assigned its Surface laptops an average repair index of 3.8, compared with Apple’s 6.3 for MacBooks.

In emailed statements provided to Grist, both Apple and Microsoft emphasized their commitment to designing high-quality, long-lasting products.

A Microsoft spokesperson said that the company “is committed to designing products that deliver what customers need and want in a premium device, including versatility, performance, cutting-edge design, and build quality along with repairability.” Apple, meanwhile, touted the energy efficiency of its devices and its use of recycled materials in recent models. The company provides “many convenient options for safe and reliable repairs,” an Apple spokesperson added.

“[T]hese scores do not reflect the actions we are taking to accelerate the transition towards a circular economy,” the spokesperson went on, referring to an economic system that minimizes waste.

While neither Apple nor Microsoft would say whether they are taking any steps to boost their products’ repair scores, smartphone titan Samsung seems to be doing so. As Purdy of iFixit noted in a recent article, a free-to-download repair manual for the Galaxy S21+ recently appeared on Samsung’s website. The release of this manual, which includes detailed instructions explaining (in French) how to repair the device, appears to have helped Samsung boost its flagship smartphone’s repair score to a respectable 8.2 out of 10. By contrast, the Samsung Galaxy S20, for which Samsung has not released an online repair manual, received a 5.7.

Samsung didn’t respond to Grist’s request for comment.

Nathan Proctor, who heads the U.S. Public Research Interest Group’s right to repair campaign, called Samsung’s release of a smartphone repair manual “unprecedented” for a major cell phone maker. Tech industry lobbyists contesting consumers’ right to repair their devices, Proctor says, will often claim that making technical documentation public means giving up proprietary company information.

“These claims are totally debunked — shown to be ridiculous — by the fact that as soon as there was a reason to publish these documents, namely to improve the repairability score, concerns over the sensitivity vanished and the materials were online,” he said.

Gay Gordon-Byrne, the executive director of repair advocacy group The Repair Association, says that because France won’t be enforcing the repairability index’s use with fines until next year, she expects some of the numbers coming out right now are “a wee bit inflated.”

“But the potential,” she said, “is terrific.”

Indeed, if companies make their devices even a little bit more repairable as a result of this regulation, that could mean millions of customers choosing not to upgrade and instead sticking with the greenest phone or laptop out there — the one they already own.