This article was copublished with The Markup, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates how powerful institutions are using technology to change our society. Sign up for its newsletters here.

New York state took a historic step toward curbing the power of Big Tech when lawmakers passed the Digital Fair Repair Act, giving citizens the right to fix their phones, tablets, and computers. For years, advocates for the “right to repair” have pushed for such legislation in statehouses nationwide. They argue that making it easier to repair gadgets not only saves consumers money, but also reduces the environmental impact of manufacturing and electronic waste. Most of those bills have failed amid intense opposition from tech companies that want to dictate how and where their products are serviced.

The passage of the Digital Fair Repair Act last June reportedly caught the tech industry off guard, but it had time to act before Governor Kathy Hochul would sign it into law. Corporate lobbyists went to work, pressing Albany for exemptions and changes that would water the bill down. They were largely successful: While the bill Hochul signed in late December remains a victory for the right-to-repair movement, the more corporate-friendly text gives consumers and independent repair shops less access to parts and tools than the original proposal called for. (The state Senate still has to vote to adopt the revised bill, but it’s widely expected to do so.)

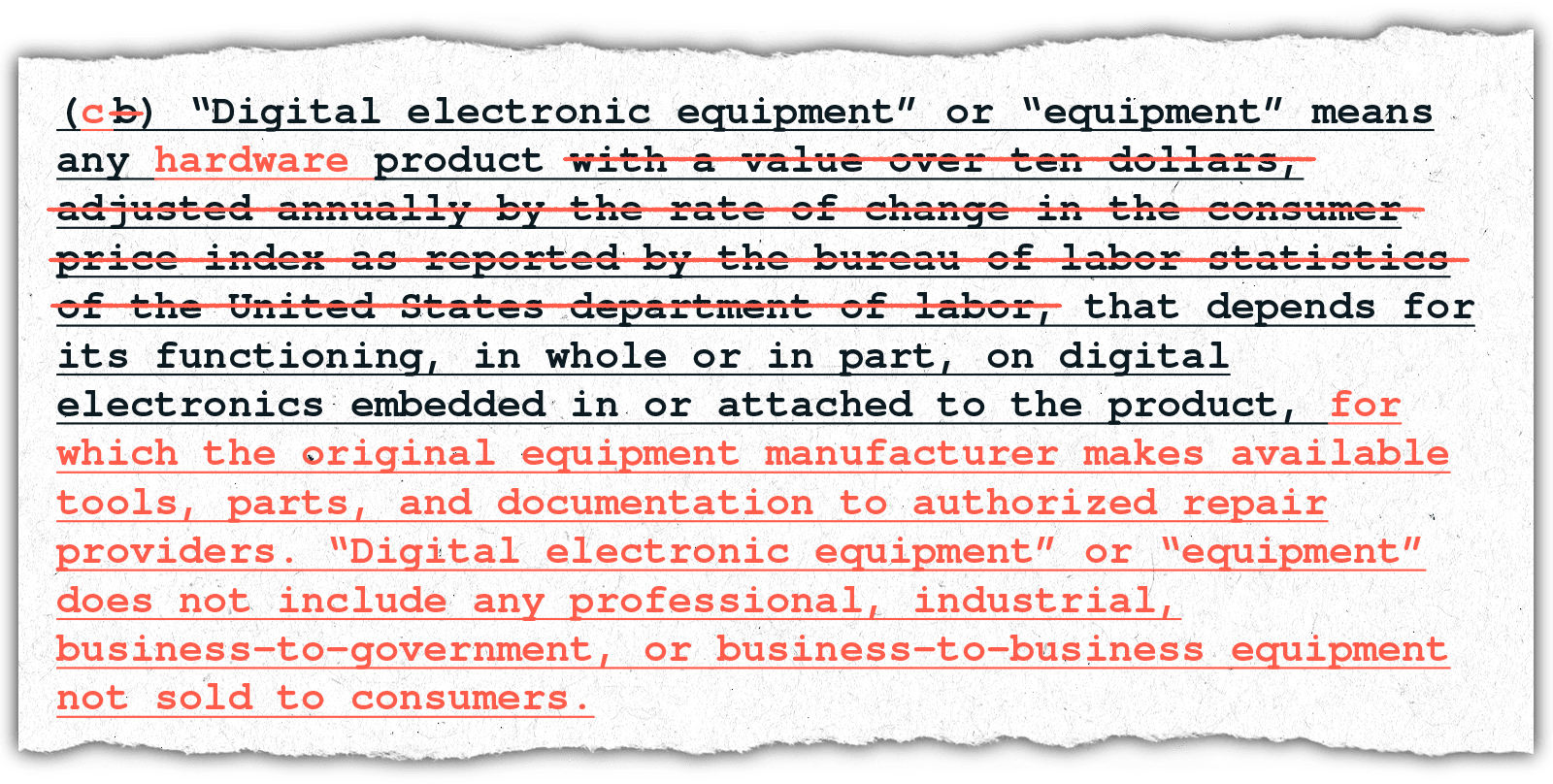

The new version of the law applies only to devices built after mid-2023, so it won’t help people to fix stuff they currently own. It also exempts electronics used exclusively by businesses or the government. All those devices are likely to become electronic waste faster than they would have had Hochul, a Democrat, signed a tougher bill. And more greenhouse gases will be emitted manufacturing new devices to replace broken electronics.

Draft versions of the bill, letters, and email correspondences shared with Grist by the repair advocacy organization Repair.org reveal that many of the changes Hochul made to the Digital Fair Repair Act are identical to those proposed by TechNet, a trade association that includes Apple, Google, Samsung, and HP among its members. Jake Egloff, the legislative director for Democratic New York state assembly member and bill sponsor Patricia Fahy, confirmed the authenticity of the emails and bill drafts shared with Grist.

“We had every environmental group walking supporting this bill,” Fahy told Grist. “What hurt this bill is Big Tech was opposed to it.”

That New York passed any electronics right-to-repair bill is “huge,” Repair.org executive director Gay Gordon-Byrne told Grist. But “it could have been huger” if not for tech industry interference.

Reached for comment, the governor’s office sent Grist a copy of a statement that Hochul released when she signed the bill, outlining changes made to the text. Her staff declined to address questions about the potential negative impacts of those changes, or about the process behind them.

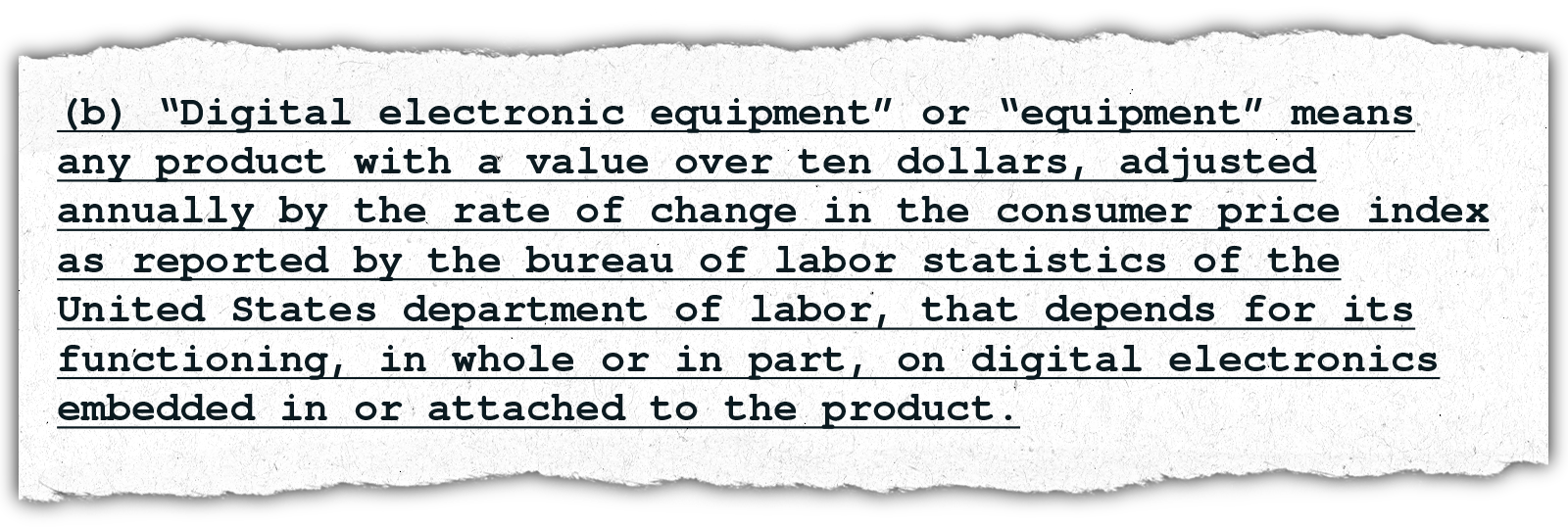

For years, consumer technology companies like Apple have effectively monopolized the repair of their devices by limiting access to parts, tools, and manuals to “authorized repair partners,” which often only perform a small number of manufacturer-sanctioned fixes. Those limited services often force consumers to choose between continuing to use a broken device or obtaining a brand-new one. The version of the Digital Fair Repair Act that passed New York’s Senate and Assembly last spring sought to level the playing field for independent shops by requiring that companies make parts, tools, and documents available to everyone on fair and reasonable terms.

A broad coalition of manufacturers opposed the bill in the spring, and its sponsors had to make significant compromises in order to pass it. “We made a lot of changes to get it over the finish line in the first day or two of June,” Fahy said.

Those changes included explicit exclusions for everything from home appliances to police radios to farm equipment. Fahy says she was willing to omit those devices because she thought focusing on small electronics would give consumers “the biggest bang for their buck.” Data from the repair guide site iFixit shows that eight of the top 10 devices New Yorkers attempted to repair in 2020 were small consumer electronics, with cell phones and laptops topping the list.

The Digital Fair Repair Act passed the Assembly by a vote of 145 to 1, after clearing the Senate 59 to 4. Despite that overwhelming support, the tech industry was surprised by its passage, said Democratic state Senator Neil Breslin, who sponsored the bill. “There’s a number of people who were advocating on the parts of the [manufacturers] who really, in private chats, were not expecting it would be passed,” Breslin told Grist.

At that point, the bill’s opponents approached Hochul seeking concessions. In particular, state lobbying records show TechNet held frequent meetings with the governor between June and December, when she signed the bill. Lobbyists representing Apple, Google, and Microsoft also met with the governor, state records show.

All of these organizations have lobbied against right-to-repair bills in other states, often citing intellectual property and cybersecurity concerns. But some, most notably Microsoft, have softened their stance in recent years. Fahy said Microsoft “constantly tried to reach out” to her office to cooperate on the bill. In a letter sent to the governor in November, the company requested several edits but did not ask for a veto. (Microsoft, Google, and Apple declined to comment.)

In letters sent to Hochul in July and August, Apple, IBM and TechNet all asked the governor to veto the bill. (IBM also declined to comment.) When a veto didn’t immediately happen, TechNet sent Hochul a trimmed-down version with edits attributed to David Edmonson, the trade organization’s vice president of state policy and government relations. Among other things, TechNet requested that the law apply only to future products sold in the state, that it exclude products sold only through business-to-business or government contracts, and that it exclude printed circuit boards on the grounds that they could be used to counterfeit devices. It also sought a stipulation allowing manufacturers to offer consumers and independent fixers assemblies, such as a battery pre-assembled with other components, if selling individual parts could create a “safety risk.” Additionally, TechNet wanted a requirement that independent repair shops provide customers with a written notice of U.S. warranty laws before conducting repairs.

Hochul’s office sent TechNet’s revised draft to repair advocates to get their reaction. Those advocates shared the TechNet-edited version of the bill with Fahy’s staff, which gave it to the Federal Trade Commission, or FTC, the agency charged with protecting American consumers. Documents that Repair.org shared with Grist show that FTC staff were highly critical of many of the changes. The parts assembly provision, one commission staffer wrote in response to TechNet’s edits, “could be easily abused by a manufacturer” to create a two-tiered system in which individual components like batteries are available only to authorized repair partners. Another of TechNet’s proposed changes — deleting a requirement that manufacturers give owners and independent shops the ability to reset security locks in order to conduct repairs — could result in a “hollow right to repair” in which security systems thwart people from fixing their stuff, the staffer wrote.

“These particular TechNet edits all have a common theme — ensuring that manufacturers retain control over the market for the repair of their products,” Dan Salsburg, a chief counsel for the FTC’s Office of Technology, Research and Investigation, wrote in an email to Fahy’s office.

Despite the agency’s stern warning, all of the changes described above, and numerous other edits TechNet proposed, appeared in the bill Hochul signed — many of them verbatim.

Chris Gilrein, TechNet’s executive director for the Northeast, told Grist in an emailed statement that the bill the Legislature passed “presented unacceptable risks to consumer data privacy and safety,” and that his organization’s recommended changes “addressed the most egregious security issues.” Manufacturers often cite cybersecurity as a reason to restrict access to repair, an argument the FTC found “scant evidence” to support in a report to Congress published in 2021.

Gilrein disputed the notion that the final version of the bill favored the tech industry. “At its core, the law remains a state-mandated transfer of intellectual property that is unwarranted at a time when consumers have access to more repair options than ever before,” he said.

Todd Bone, the president of XS International, a company that maintains and repairs network and data center IT equipment for corporations and the federal government, says the law offers “nothing” to his business because of the governor’s carveout for devices sold under business-to-business or government contracts.

“It was very disheartening,” Bone told Grist, “to see the governor working with TechNet and not paying attention to the votes from the Congress and the Senate in the state of New York, [and] what the consumers of the state of New York wanted.”

Jessa Jones, who founded iPad Rehab, an independent repair shop in Honeoye Falls, about 20 miles south of Rochester, New York, says the original bill included provisions that would have made it far easier for independent shops like hers to get the tools, parts, and know-how needed to make repairs. She pointed to changes that allow manufacturers to release repair tools that only work with spare parts they make, while at the same time controlling how those spare parts are used, both of which were requested by TechNet.

“If you keep going down this road, allowing manufacturers to force us to use their branded parts and service, where they’re allowed to tie the function of the device to their branded parts and service, that’s not repair,” Jones said. “That’s authoritarian control.”

After repair advocates shared TechNet’s draft with Fahy’s office, they collaborated on a counterproposal that pushed back against many of the proposed changes. The last-minute negotiations with the governor’s office were “frustrating,” Fahy said, although she still ultimately wants to see the bill become law.

Fahy hopes the New York Department of State will clarify aspects of the bill that got muddied by industry influence. The agency, which plays a role in consumer protection, will craft regulations dictating how the law will be implemented. Ultimately, Fahy says the bill will still help consumers save money and keep old devices out of landfills. And every little bit counts: In New York state alone, the U.S. Public Interest Research Group estimates that Americans discard roughly 23,600 cell phones per day.

Fahy also believes the law — imperfect though it may be — will have a ripple effect beyond the state’s borders. It could give momentum to the efforts to pass similar laws in dozens of other states. Eventually, the passage of state bills could lead to a national agreement between electronics manufacturers and the independent repair community, similar to what happened in the car industry after Massachusetts passed an auto right-to-repair law in 2012.

Other lawmakers agree that New York has provided a welcome starting point.

“When you’re the first state, sometimes you have to pass something very small to get across the finish line,” Washington state representative Mia Gregerson, a Democrat who is sponsoring a digital right-to-repair bill in her state’s house, told Grist. New York’s Digital Fair Repair Act, Gregerson said, “gives us something to work from.”

“We’re going to take that now and try to do a better piece of legislation,” Gregerson said.