If cities are the greenest form of human settlement that we could possibly aspire to, Jane Jacobs left us the owner’s manual for how to build them.

If cities are the greenest form of human settlement that we could possibly aspire to, Jane Jacobs left us the owner’s manual for how to build them.

Fifty years ago this month, Random House published The Death and Life of Great American Cities, an extraordinary book in which Jacobs laid out the principles for creating a healthy city. The blocks must be at a human scale, she said. There must be a diversity of activities to keep eyes on the street. The focus of the economy — of everything — should be local, typified by Greenwich Village, the Manhattan neighborhood where she chose to live.

A half-century later, the concepts of mixed-use, moderately dense, walkable urban environments are uniformly embraced by the planning professions, and by the movements of New Urbanism and smart growth. Yet the legacy of Jane Jacobs and this remarkable treatise is decidedly mixed. Today, she is invoked in campaigns to stop the very kind of urban development she advocated.

The story of how Jacobs came to write Death and Life reads like a movie script. A housewife from Scranton with no college degree, she came to New York City, fell in love with its old neighborhoods, and worked her way from secretary to editor and writer at several magazines. She was content in her life on Hudson Street until she learned of a plan by New York’s master builder, Robert Moses, to put a roadway through Washington Square Park, where she took her children.

The project struck her as exactly the opposite of what the city needed, and as Jacobs began to look around, she saw many other similar examples. It was the heyday of “urban renewal,” but cities, she felt, were being ravaged by planners’ devotion to the smooth flow of traffic and utopian visions for how people should live that were divorced from reality.

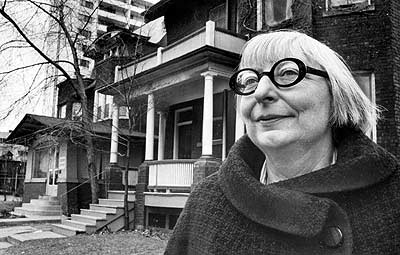

Jacobs went to Harvard in 1956, representing Architectural Forum magazine, and shared her observations that urban planners were getting it really wrong. She met urban thinkers Lewis Mumford, Holly Whyte, and Jason Epstein. She got introduced to someone from the Rockefeller Foundation, who arranged a grant, and she sat down at a typewriter and wrote her book.

When Death and Life came out in November of 1961, it was soon apparent this was a book to change the world. Moses and other planners sat at drafting tables with blinders on, she wrote. City governments, the business establishment, modernist architecture, Le Corbusier’s towers in the park, the bulldozers of urban renewal — all of it ruined the promise of the metropolis.

The book was a shock to the status quo, similar to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring or Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. And it gave power to the people. A fundamental theme was that ordinary citizens were not being consulted about the very communities they lived in. The planning was going on entirely behind closed doors. In taking on Moses, Jacobs rallied New Yorkers to fight City Hall, storm planning hearings, gather signatures for petitions, and organize protests.

The public is now intimately involved in the process. No government planner and no developer would dare make a move without a raft of hearings. Community design gathers input for city-building by committee. And this is where, 50 years later, the contradictions start to arise.

As a pioneer in the west section of Greenwich Village — which around World War II was a diverse community of dock workers — Jacobs helped set the stage for gentrification. She recognized that great city neighborhoods needed more affordable housing, and she got behind one project, the West Village Houses, that she hoped would be a “windbreak” against real estate speculation. But today her old neighborhood — as well as south to SoHo and Tribeca, and north to the Meatpacking District near the elevated park, the High Line — is as rarefied and celebrity-studded as one can imagine.

And Jacobs’s crusade for citizen involvement 50 years ago has led to so much public process that NIMBYs — those who say, “not in my backyard” — can control the agenda. In Boston recently, residents nearly a mile away objected to the redevelopment of a vacant, trash-strewn lot next to the JFK-UMass transit station. They were worried about parking and traffic congestion and more people and density and tall buildings. In Palo Alto, residents are fighting a new high-speed rail line — common in Europe and Asia — though the line would run along the existing CalTrains alignment.

In writing The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs revolutionized the business of urban planning. She battled Robert Moses on some truly bad projects — the roadway through Washington Square Park, the Lower Manhattan Expressway, and housing towers that would have wiped out perfectly good neighborhoods under the policy of slum removal and urban renewal. She was David to Moses’ Goliath, all the more thrilling because she triumphed as a woman where mayors, governors, and even presidents failed.

But the 21st century city — the green city — requires thinking big at least in some respects. It requires being creative in financing, knowing how to navigate the bureaucracies, and having a vision for large metropolitan areas and how they fit it into megaregions. Jane Jacobs’s legacy is indeed towering, and the achievement of Death and Life unparalleled. But the future of cities could use a touch of her nemesis mixed in.