C40 Cities, Michael Bloomberg’s coalition of global mayors trying to tackle climate change on their own, reported Wednesday that their progress is accelerating. Five-dozen of the world’s biggest cities (the group actually has more than 40 members) have nearly doubled the number of programs and initiatives they’re implementing to adapt to climate change or reduce emissions in the last two years. Among the group, they’ve now got 36 bikeshare systems. Fifty-two cities are planning to phase in LED streetlights. Another 35 are working on BRT.

Fifty-eight out of 59 municipalities that participated in a mammoth status report out today at C40’s biannual meeting declared that climate change poses significant risk to their cities (the lone dissenter isn’t named). And that, points out C40 research director Seth Schultz, is a refreshing level of agreement on the topic (although maybe it’s not that surprising coming from mayors who want to be in a group devoted to climate change in the first place).

“There’s still some debate about whether climate change is actually happening,” Schultz says, by which he means outside of C40. “This is for me one of the most exciting data points coming out of this [report]: This absolutely universal, ubiquitous consensus among cities that this is not a debate. It’s happening, and it poses a serious threat to our cities.”

The logical question that follows, though, is whether cities trying their darndest to prepare for that future can get very far on their own, in the absence of global protocols and national policies. Bloomberg, a newly minted U.N. special envoy for cities and climate change, founded the group on the premise that they can.

No doubt cities have many levers to pull. But so many of them are small: a hybrid bus here, a pedestrian plaza there, a new case of LED lightbulbs. The primary unit of measurement in the new C40 report is an “action,” any single method taken by a city — through regulation, procurement, projects — to tackle climate change. Upgrading bus stops to incentivize greater transit use counts as an action. So does implementing congestion pricing, or a new recycling system, or an energy benchmarking law for buildings.

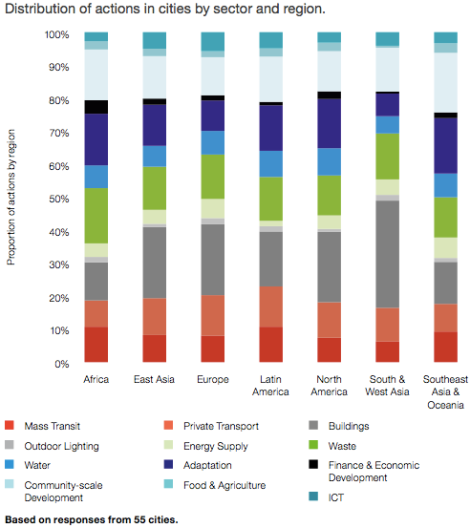

By the report’s count, these 59 cities have set in motion some 8,000 such actions in a broad range of sectors:

That number has limited meaning, given that a new bike lane counts as much as a tax rebate for solar installation. But the report includes an interesting account of where cities feel they have power, and how that municipal power varies across the globe.

By a sheer count of “actions,” U.S. cities responsible for the largest emissions have also been taking the most steps to curb them and to adapt to rising seas or hotter summers. But, in a fascinating way, mayors in the developing world and in Asia actually wield way more centralized influence on how waterways or regional parks or private buildings are regulated.

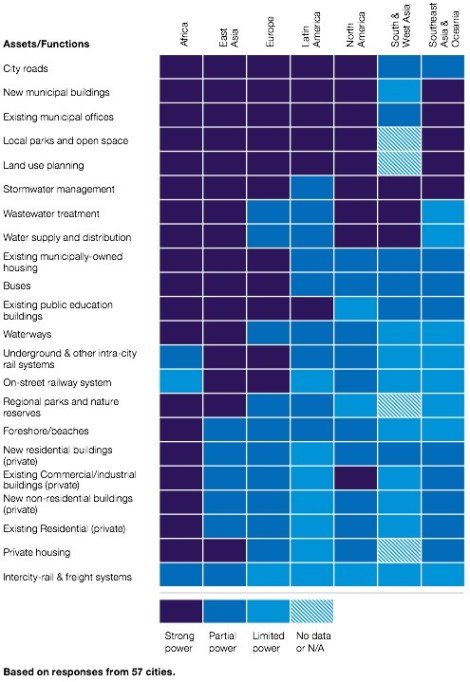

Mayors in each city were asked how much control they have over individual assets like streets or transit systems, or over functions like economic development that might be leveraged to tackle climate change. These are the results looking at water infrastructure and climate adaptation:

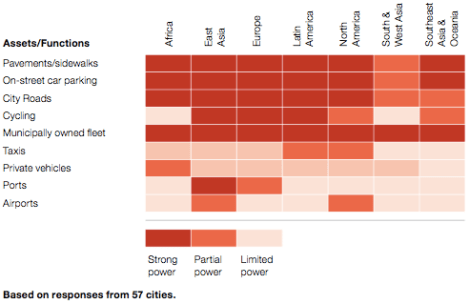

If they wanted to, African mayors could actually single-handedly have a greater impact on greening their cities than U.S. mayors could — up to and including enforcing regulation on private housing. This is the similar picture with mass transit:

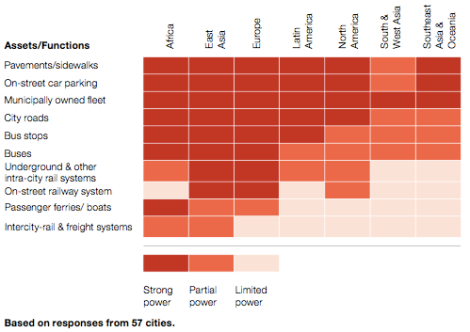

And with private vehicles:

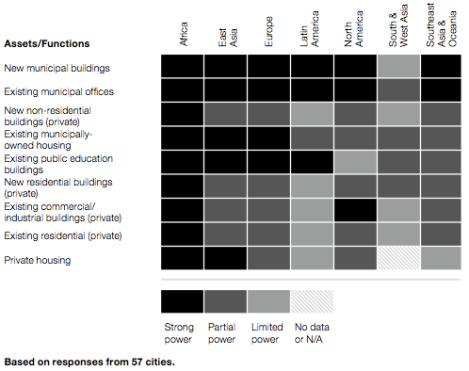

This matrix reflects mayoral power over the buildings sector:

Click to embiggen.

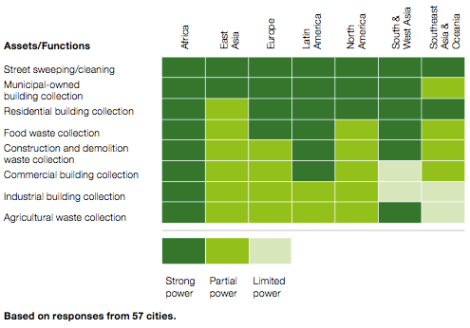

And over waste reduction and collection:

These charts reflect the fact that city governments control much even if they have no control over national policy. Simply by managing roads they get to set parking policy, discouraging or incentivizing driving. By owning schools and government offices, they can impact at least some of the energy use by the building sector. By providing garbage collection, they can influence how much residents recycle.

That power, though, is tempered by politics and by the very structure of city government itself.

This story was produced by The Atlantic Cities as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by The Atlantic Cities as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.