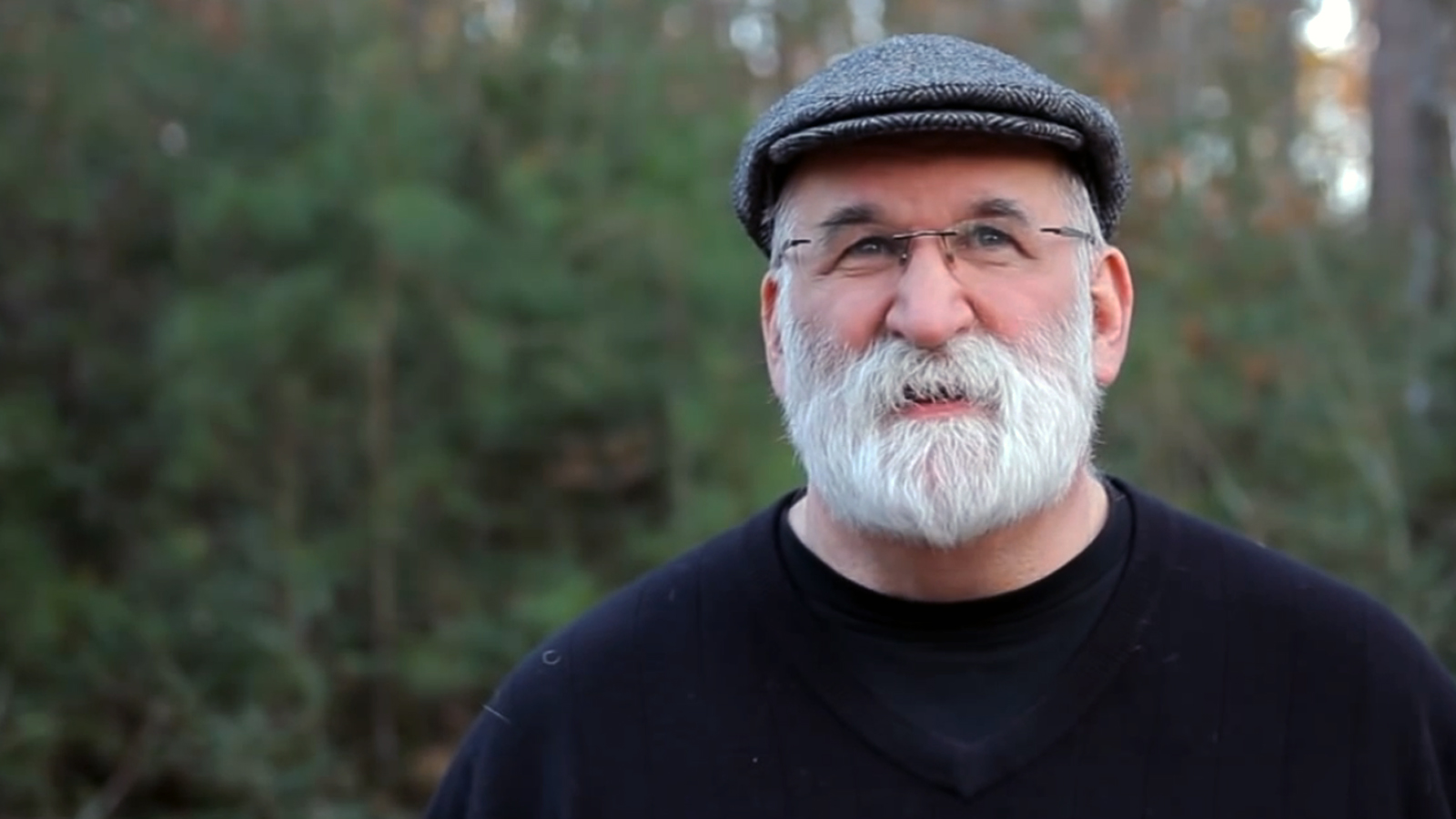

This past summer, I interviewed Alec Johnson, the 62-year-old who locked himself to an excavator sitting on a pipeline easement site for Keystone XL in Atoka, Okla., back in April 2013, as part of the Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance. As it turned out, getting arrested was the easy part. More than a year later, Johnson still hadn’t gone to trial — because in rural Oklahoma, communities only hold jury trials once or twice a year, and he kept getting bumped further down the court calendar behind more felonious criminals.

Last week, nearly a year and a half after he was first arrested, Johnson finally got his day in court. It was a speedy, one-day business: jury selection in the morning, trial in the afternoon. Johnson and his lawyer, Douglas Parr, managed to get one potential juror removed after he said that climate change was something Al Gore invented to make money.

They were, however, disappointed that the judge didn’t let them use the necessity defense during the trial — which would have let Johnson argue that he chained himself to the excavator because he believed that it would stymie the greater wrong that is climate change. The necessity defense has a long and complicated history when used to justify civil disobedience and, these days, it’s difficult to get the right to use it in a trial.

A successful use of the necessity defense is the holy grail right now for climate change-related civil disobedience, but it’s only been granted once — this past September, for the trial of Ken Ward and Jay O’Hara, who used a lobster boat to block a coal barge in Massachusetts. Ward and O’Hara’s legal team had a gangbuster of a defense in the works, with both Bill McKibben (who is, full disclosure, on Grist’s board) and James Hansen appearing as expert witnesses; but Ward and O’Hara wound up accepting a plea deal and never going to trial.

“The jury got that I wasn’t a run-of-the-mill criminal,” said Johnson, about the trial. “The courtroom was packed with supporters — that definitely helped me on the stand. By all reports, I did very well.” It was clear that Johnson had chained himself to the excavator for a reason. “I got to use the line ‘I don’t have trillions to look after, I have children to look after,'” he said. “That made it onto Twitter.”

But every time Johnson got into the specifics of climate change — the signed letter he had from James Hansen; the amicus brief from Mary Wood, a law professor specializing in Public Trust Doctrine that has been used by Our Children’s Trust; the National Climate Assessment — he was told to stop talking. The last prohibition was particularly baffling to Johnson: “I find it passing strange that a national document mandated by an act of Congress couldn’t be admitted into a jury trial.”

Even though Johnson wasn’t allowed to mention climate change, the jury still went easy on him. There was no jail time, though the judge doubled the fines recommended by the prosecutor and levied the maximum for each count: $500 for obstructing a public official, and $500 for continuing to talk to some supporters after the police officer arresting Johnson told him to stop talking (which apparently also counts as obstructing a public official). The judge also charged him $545 for the cost of putting on the trial.

The jury returned its verdict quickly — “I think they wanted to get home,” said Johnson. Johnson is delighted that a year and a half of planning for a trial in rural Oklahoma has come to an end, and that the jury didn’t think he was a serious danger to society.

Still, he wants to explain to the jury the reason behind what he did — and now that the trial is over, he’s no longer legally barred from doing so. “I’m writing a piece,” he said, “with a working title of ‘What I Would Want to Tell the Jury.'”