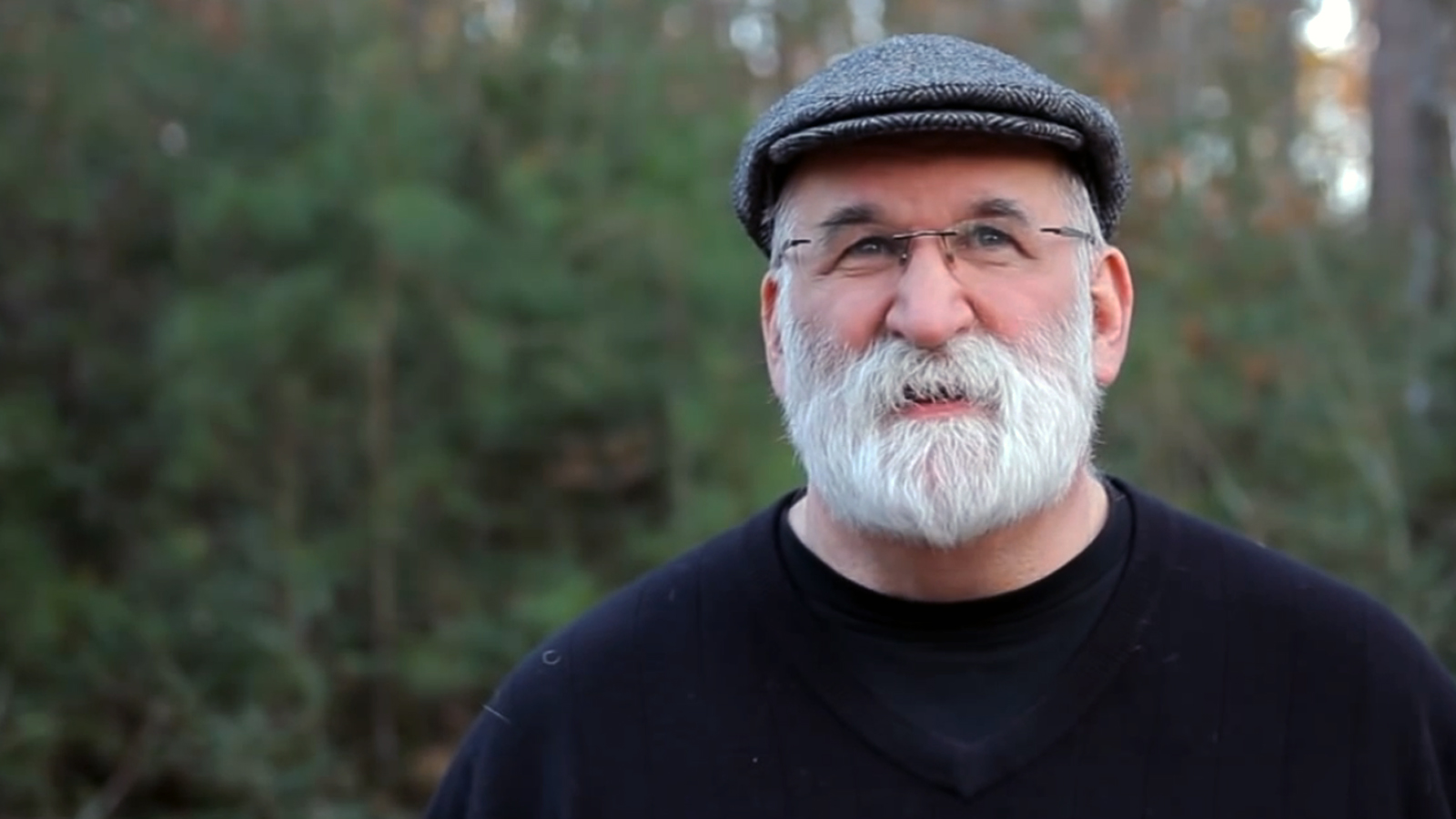

It’s been over a year since Alec Johnson was arrested for locking himself to an excavator sitting on a pipeline easement in Atoka, It�

A lot has changed in that year. The protest around U.S. energy policy and climate change has shifted fronts – coal terminals, oil-by-rail, divestment, solar, and a massive climate rally planned for this September. Keystone XL South (now renamed the Gulf Coast pipeline) is up and running and being monitored by an ad hoc group of volunteers. Keystone XL is on hold until after the November U.S. elections — possibly for good, though Johnson has his doubts. “In my experience, the ruling class pretty much gets what they want when they want,” he says.

Johnson has been arrested seven times, though there’s a gap of several decades in the sequence. The majority of his arrests happened in the mid-’70s, outside of the Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant in Seabrook, New Hampshire. Johnson was a member of a direct-action group called the Clamshell Alliance, and getting arrested was a whole different business then. “I got the shit kicked out of me,” he said. “They had their badge numbers taped over. A lot of white people that doesn’t happen to, but it happened to me.”

The anti-nuclear movement of the ’70s and ’80s is regarded in some circles as one of the most successful environmental direct-action movements in US history. But Johnson, again, has his doubts. “We still have the Price-Anderson Act, which ensures that we the people pick up their insurance tab. We still have millions in loans for people who want to build them.”

Johnson credits the anti-nuclear movement’s effectiveness more to disaster than activism. “Three Mile Island went from being a multi-million dollar asset to a multi-million dollar liability in one night.” He pauses. “That said, if I was given a choice between leaving an existing nuclear plant running and building new coal plant, I would leave the nuclear plant running.”

Johnson grew up in a family that was not particularly environmentalist or activist — but it was extremely interested in science. Johnson’s mother, the author Anne McCaffrey (of Dragonriders of Pern fame), worked hard to use it accurately in her fiction. “Scientists would fall all over themselves trying to help her do something like talk intelligently about how to sight a telescope,” Johnson says, “I saw it happen.”

Back then, says Johnson, America was in love with scientists. “I remember watching Kennedy, when he said, ‘We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.’ ” But by the time climate change began to be talked about, something had changed. “It’s baffling to me,” says Johnson. “The threat is clear. It’s serious. Scientists have told us that it’s serious, and these are people who tell the truth for a living.”

After the Clamshell Alliance, Johnson didn’t see much point in getting arrested anymore. He moved to Ireland. He moved back. He got involved in political organizing.

Keystone XL changed that. In August of 2011, Johnson found himself, along with 1,252 other people, getting arrested in front of the White House for protesting the pipeline.

A year and a half later, Johnson, sat in on a talk given Lauren Regan, of the Civil Liberties Defense Center. Regan was briefing a group of activists who were marching on the Texas headquarters of pipeline builder TransCanada. Regan did not mince words: if they went inside the headquarters, they would be arrested, and in Texas, that was not going to be fun.

By the end of the talk, only two people out of the crowd of a hundred still planned on walking into the headquarters proper. Johnson was one of them.

Unlike Central Booking in Washington D.C., where the White House protesters got sent, the jail in Harris County, Texas, wasn’t so bad. They served grits and eggs with hot sauce for breakfast, and the other inmates named Johnson “School” after his propensity for explaining global warming to everyone. Thirty-six hours later, he was taken to court, where he paid a $300 fine and left.

Johnson could have pled guilty and paid a fine in this case, too. Instead, he’s hoping that a jury trial could result in a useful precedent. There’s an argument known as the “necessity defense” – basically, that you committed the crime you were arrested for out of necessity, to prevent a larger crime from happening. While it is a defense often used by activists, is is not one that often works. Johnson plans to combine the necessity defense with a heavy dose of public trust doctrine. A ruling in his favor could set a precedent that would help other climate activists down the line.

On the other hand, a ruling against Johnson could land him in jail for a year or two, which is not a fun prospect for anyone, let alone a 62-year-old. “I can’t say that I’m particularly looking forward to going to jail,” says Johnson. “My lady love wouldn’t like it either. But I’m the father to two daughters and I truly take this seriously. It shouldn’t be this hard to protect the environment.”