On Friday, Sept. 27, the low-lying island nation of the Maldives will be given the date of its extinction; notice of a death by drowning. It will come in the form of a prediction for future sea-level rise in a landmark report on global warming by the world’s climate scientists. On current trends, anything more than three generations will feel like a reprieve.

On the packed streets of Male’, the mini-Manhattan that serves as the Maldives’ island capital, there is a political clamor. But, perhaps surprisingly, the cause is not worry about the existential threat posed by the rising seas but over accusations of corruption and vote-buying in the presidential election.

Mohamed Nasheed, the nation’s first freely elected leader and darling of the west for his warnings about climate change, was expected to be restored to the presidency in this month’s elections. However, the vote that was supposed to restore Nasheed to the presidency is currently suspended following a complaint from the candidate who came third in the first round of polling.

Mohamed Nasheed.

The issue of climate change — even given the credentials of Nasheed, the first round poll leader — was as invisible during the country’s election campaign as the carbon dioxide that drives it.

On the resort islands that underpin the Maldives’ economy, it is hard to imagine the paradise atolls are on the frontline of climate change. Under the aquamarine water, iridescent parrotfish and myriad others prune the pink and green coral reef while squid pulse with purple phosphorescence over gliding hawksbill turtles. But a few kicks of the flippers further on and the scorching aftermath of the 1998 and 2010 bleaching catastrophes are clear, with broken coral rubble strewn on the sea floor like broken bones and masonry on a bomb site.

This sliver of an island nation, home to nearly 400,000 people, is literally built on tall coral columns perched on ancient underwater mountains. Friday’s landmark report on global warming from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — which is currently being finalized by a meeting of the world’s top climate scientists along with political observers in Stockholm — will set out the extreme precariousness of this position.

For coral reefs, the 800 climate scientists behind the report will be forced to add a new color — purple — to the top of their range of risk levels to signify how much the dangers have worsened since the last IPCC assessment in 2007.

A significantly higher estimate for future sea-level rise is expected, up to 97 centimeters (38 inches) by 2100, and this poses the most obvious threat to an archipelago where most land is no taller than an 11-year-old child. But rising sea temperatures will also increase coral bleaching and crumbling — where the reef gradually dies because the colored algae that live within and help to feed the corals are expelled as the water warms.

“Our islands are not rocks in the ocean, they are dynamic, natural systems and the changes [caused by climate change] are making life difficult or even unbearable for species like humans,” says Mohamed Aslam, until 2012 the environment minister in Nasheed’s government. “If we were birds we would simply fly to Sri Lanka, but we build houses and settle.”

The new IPCC report, which will be signed off by the world’s governments, will also describe the increasingly extreme and erratic weather being driven as the planet heats up. At the Maldives National Meteorological Center, Deputy Director Ali Shareef says: “There is no doubt climate change is having an effect here in the Maldives. Nowadays, we find severe weather events two to three times a year but a decade ago they might only happen once every year or two.”

Bigger ocean swells are driving waves right over the islands, he says, contaminating with salt the thin lenses of fresh groundwater beneath, while thunderstorms are causing flash-flooding and knocking out power systems. The waves also drive erosion of the islands, accelerating a natural process that can shift an island over 30 meters (98 feet) in a decade.

“Eighty to 90 percent of the inhabited islands see some erosion and these freak weather events are becoming more common,” says Shiham Adam, general director at the Marine Research Center. The degradation of the coral, the key breakwater of the ocean’s energy, further exacerbates the problem.

Adam says the warming oceans may also be affecting the tuna industry — the Maldives’ most important after tourism — where catches fell by 40 percent from 2006 to 2011. The tuna may move to cooler water and out of the reach of the pole and lines used in the Maldives, he says. Or perhaps the decline results from a lack of food, caused by changing weather patterns.

The untangling of climate change impacts on the tuna population from natural cycles — or from other human impacts, such as overfishing — will be a key new part of the IPCC report. In the Maldives, the paucity of long-term data makes it particularly tough. The meteorology center has just 40 years of data and does not have the equipment to measure the sea’s temperature or wave heights. Sixteen of its 22 automatic weather stations are broken due to lack of money for maintenance on remote islands.

“We are a small, developing island nation: We are never going to have 200 years of data,” says Simad Saeed, managing director of the CDE environmental consultancy, who has worked on many government projects. But he says there is enough now to be sure of changes, if not their exact scale. He points to the extending and intensifying of the dry season, worsening the drinking water problems, which already sees drinking water being shipped to over a quarter of the 196 inhabited islands.

Saeed also points to a worrying development in the wet season: a rise in dengue fever. “The hotter and wetter conditions are perfect for the mosquito: this is the main impact of climate change in my opinion,” he says, although the government health campaign is focusing on potholes on construction sites where mosquitoes can breed.

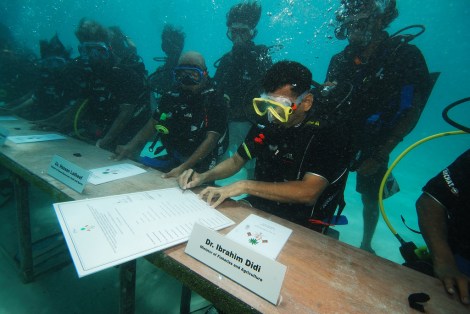

Nasheed, whose attention-grabbing campaigning on climate change has involved holding an underwater cabinet meeting in 2009 and being named by David Cameron as his “new best friend” in 2011, was ousted in February 2012. That derailed his pledge to make the nation carbon neutral by 2020: blackouts are now seen as more likely in Male’ in the next two years as demand is growing but there is no land left for more diesel generators. Another pledge — to make the entire 1,000 kilometer- (621 mile-) long island chain a marine reserve by 2017 — also looks troubled.

But in tiny Male’, whose 110,000 people make it the most densely populated land on Earth, the fluttering everywhere of the red and yellow streamers of the presidential rivals indicates the public’s concern is not about the environmental threats to the Maldives. “If I woke up one day and the islands were going underwater, I’d just move,” says Mohamed Arzan, a taxi driver.

Climate change issues have been absent from the political campaigning, apart from one candidate’s striking pledge to explore for oil in the Maldives. Saeed says issues such as changing water availability are being ignored: “Drinking water is a fundamental human right, but direct cash [welfare] payments get more votes.”

Nasheed’s pledge of $1 billion in welfare payments in the next five years, plus the quarter of GDP spent on the diesel that powers the nation, would give little room for spending on climate adaptation without foreign aid in an already heavily indebted nation. “The cost of oil is bleeding them dry,” says Mike Mason, the British engineer who developed the stalled carbon neutral plan. He adds that governance issues have exacerbated the problem. An official of the country’s environmental protection agency told the Guardian that its rejection of a major resort development was rendered meaningless, because the developers had already acquired the rights to start work.

However, one striking response to the threat of inundation has gone ahead. An entire new island, called Hulhumale’, has been created from sand dredged from the lagoons. When the second phase is finished, the 420 hectares (1,037 acres) will house 160,000 people, a third of the entire population. By Maldivian standards, the new island is lofty, at two meters (6.56 feet) high. “It is the safest island in the Maldives, from sea level at least,” says Ahmed Varish, at the Hulhumale’ Housing Development Corporation, standing outside the large social housing blocks.

How safe that vantage point is will be revealed in the new IPCC report. But whatever its findings and however politicians and nations respond, former environment minister Aslam is clear that, for better or worse, the Maldives is the frontline of the battle against climate change. “Whatever happens to us will happen to the rest of the world — it is just a matter of time.”

This story first appeared on the Guardian website as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story first appeared on the Guardian website as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.