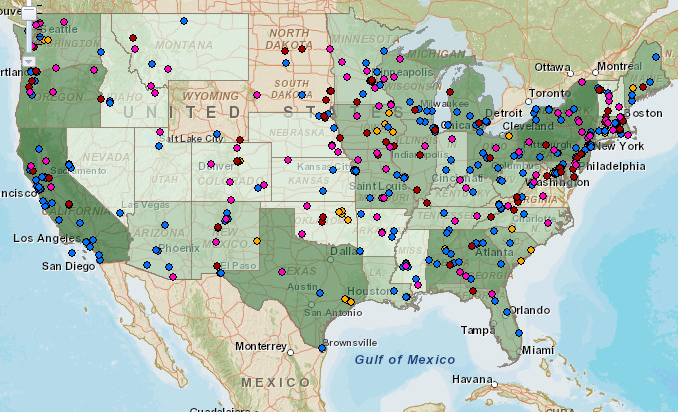

Yesterday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) released what it’s calling the “2.0 version” of its Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food Compass. For those not in the know, the Compass is a map of all of the local food projects — including farmers markets, food hubs, infrastructure, and producers — the USDA funds.

The Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food (KYF) initiative itself is the brainchild of USDA Deputy Secretary Kathleen Merrigan — possibly the highest ranking supporter of sustainable agriculture we’ve ever had at USDA — as a way to highlight efforts to aid local foods.

I’m a big fan of mapping as a visualization tool and the Compass certainly provides lots of data. That said, it’s not really much of a consumer-focused tool compared with private efforts like RealTimeFarms.com, which not only maps farmers markets and farms, but also shows the links between particular restaurants and their local artisanal and farm suppliers.

Instead, the KYF Compass is a way to illustrate what Merrigan and her team are accomplishing. The Compass demonstrates the national reach of USDA-funded local food products; there are little dots all over the country and in every state. Similarly, the KYF website has new local food “case studies” that spell out the department’s recent work. Here are some examples:

- Calling Local Meat Processors: USDA is Here to Help

- In Remote Sections of Rural Nevada, Healthy Food Grows Locally

- Local Food Drives Small Business Growth in Southwest Wisconsin

- A New Business Model Proves Lucrative for Grass-Based Dairies

- Building a regional food system in Wyoming, a “value-added desert”

The Compass also proves that local food isn’t just a coastal phenomenon; it’s thriving in Nevada, Wisconsin, and Wyoming, too (and also, you know, Micronesia).

The stories themselves are pretty cool, but it’s also worth considering the Compass as a very conscious effort to paint a picture of KYF as benefiting a broad range of regions and businesses.

For example, the local-meat case study in Seattle features a librarian-turned-sausage-maker who wanted to open a USDA-inspected sausage factory in his garage. And, with the help of the right folks at USDA, he succeeded. The Wisconsin story describes a virtuous circle that begins with hoop houses on small farms to extend growing seasons, which led to an increase in so-called “value-added food business” (i.e. artisanal products like jam and pickles), which led to jobs and higher incomes.

It’s worth noting that KYF itself doesn’t provide any new funding — it has simply drawn a connection between preexisting projects run through an alphabet soup of USDA divisions in order to strengthen the message that the agency supports local and regional food. And while it might seem that KYF would be entirely uncontroversial in Washington, it’s not. In fact, almost from the moment of its inception, the effort has raised the ire of Republican lawmakers, who see it as a distraction from USDA’s “real” job of supporting industrial agriculture.

Indeed, the House GOP tried to kill the KYF program last year, along with other attempts at reform. It was an effort that mostly just involved attempts to force USDA to take down the KYF website. KYF survived — but not without a requirement to submit a report of its work to Congress; the Compass is very clearly a part of that reporting.

Not that the GOP was content to leave things there. As we reported back in March, when the Compass was first launched, Sen. Pat Roberts (R-Kan.), the top Republican on the Senate Agriculture Committee, quipped that the whole KYF effort was not “‘steeped in reality’ … since most food Americans consume isn’t grown locally.” Of course, I could argue that continuing to plant millions of bushels of corn in regions that grow more and more drought-prone every year isn’t exactly “steeped in reality” either, but I digress.

The point is that the KYF Compass and the case studies that the KYF website highlights are directed as much at congressional legislators as they are at small farmers and consumers. I’d even go farther than that — the Compass is part of an effort of build a permanent and self-sustaining infrastructure for federal support of local food at USDA, an agency that has, for some time now, lacked it.

Kathleen Merrigan will not be deputy secretary forever — nor will Democrats forever control the White House. And we have seen how quickly a determined effort can dismantle years of regulatory progress (case in point, the George W. Bush EPA). But by demonstrating to Congress and to her own officials and workers the broad reach and significant economic benefits of the local and regional food efforts, Merrigan is likely betting that KYF won’t be so easy to kill.

We’ll have to wait and see how this plays out — but there’s no question that Merrigan knows her way around institutions like USDA. After all, she is the person who not only helped write the USDA organic legislation, but then turned around and implemented it successfully as director of the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service under Bill Clinton, despite industry efforts to water it down to nothing. It may be that she’s attempting to perform a little bureaucratic jujitsu on a rigid agency. Here’s hoping she succeeds.