For the past three years, the Valero Houston Refinery hasn’t gone a single quarter without committing a significant violation of the Clean Air Act. Year after year, as toxic air pollution has wafted through Manchester — a predominantly Hispanic, low-income neighborhood across the street — the facility has racked up a long list of violation notices from state regulators, but that’s done little to actually stop the onslaught.

“We always voice concerns about non-enforcement,” said Juan Parras, executive director of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services, who has advocated for Manchester and other communities along the Houston Ship Channel for more than 20 years. “Even when there is enforcement, the penalty is so ridiculously low that it doesn’t pressure the industry to clean up,” he said.

To Parras, this is unconscionable. “We ought to be showing communities that are impacted like we are — throughout the nation — that the law is going to back them up,” he said.

The Valero Houston Refinery is just one of 485 facilities across the country with “high priority violations” of the Clean Air Act that have been left unaddressed through formal enforcement actions. Those violations could include operating without a permit or not using the best available technology to control emissions, among other infractions.

At the federal level, EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance is responsible for enforcing environmental laws. The division runs programs to assist companies with compliance, carries out investigations into suspected violations, issues penalties, and refers the more severe violations to the Department of Justice for prosecution.

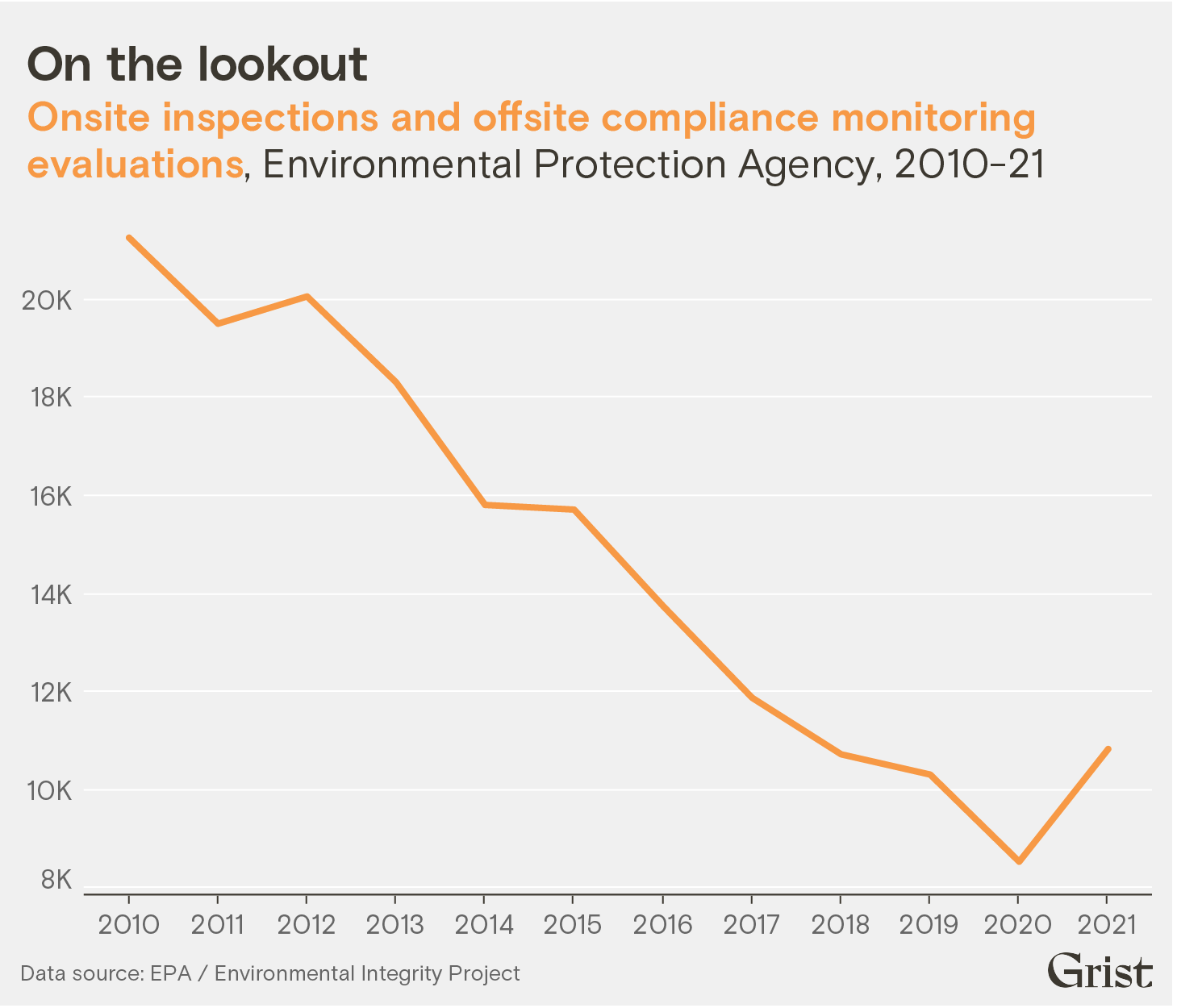

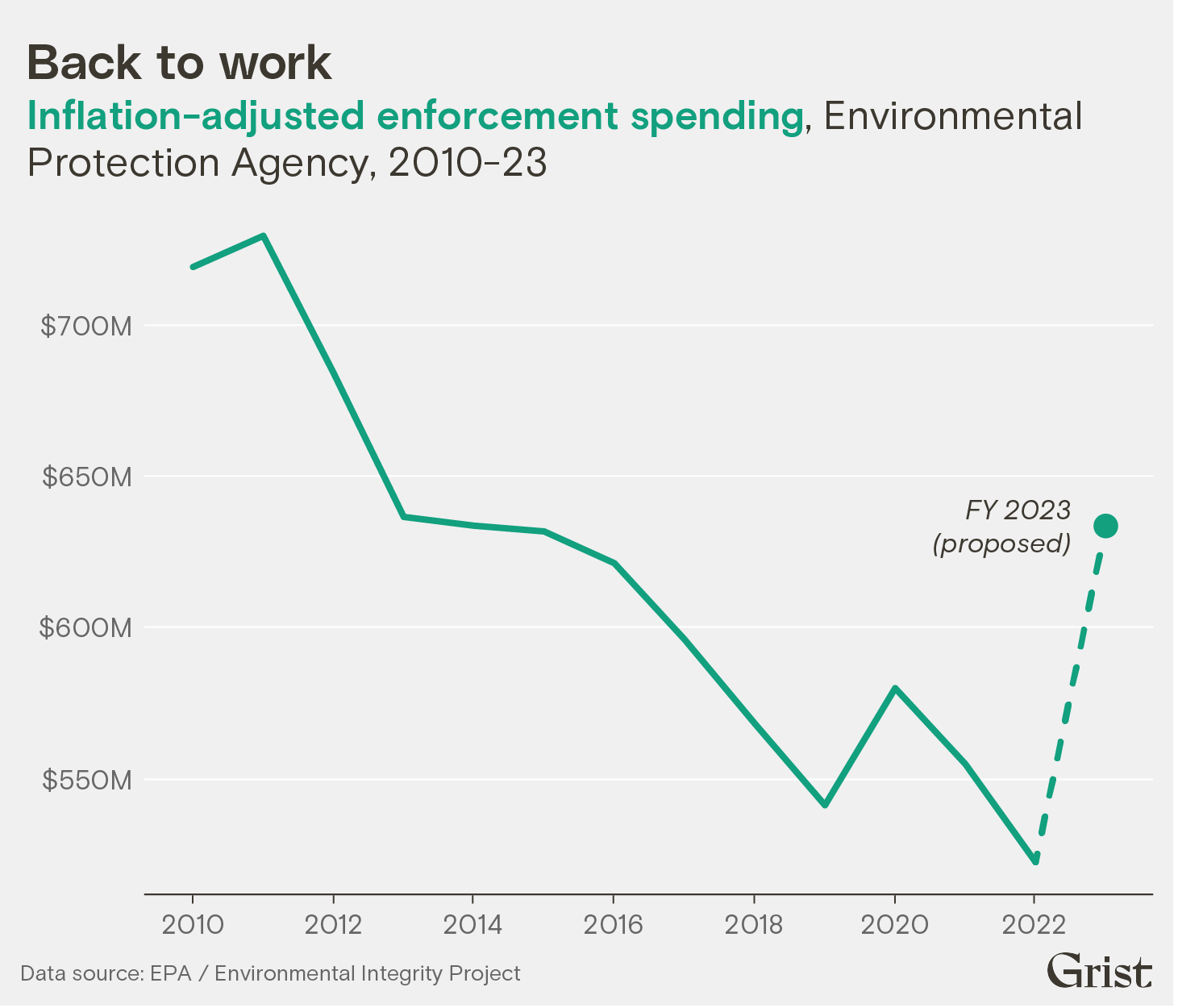

But for the past decade, Congress has steadily chipped away at the enforcement division’s funding and staffing levels. Since 2011, enforcement funding has fallen by nearly 30 percent once adjusted for inflation. The division currently has 713 fewer staffers than it did back then — a decrease of about 28 percent. As a result, the number of inspections, investigations, and civil and criminal cases the division initiates each year has plummeted, too. There’s a backlog of violations that the EPA hasn’t taken enforcement action on, and there are likely many more that the agency doesn’t even know about because investigators aren’t examining the data companies report or getting out into the field as often.

That has real-world consequences for neighborhoods inundated with industrial pollution, which tend to be communities of color or low-income communities. When it comes to enforcing the law, “if our state’s not going to do it and our EPA can’t because they don’t have the capacity, then now there’s nobody left, right? There’s nobody who can hold polluters accountable,” said Jennifer Hadayia, executive director of the environmental justice non-profit Air Alliance Houston.

Environmental justice advocates hope Congress will soon reverse course and begin building the enforcement division back up. Last week Air Alliance Houston and 26 other environmental groups from across the country urged lawmakers to fund the EPA’s enforcement efforts at the levels proposed in the Biden administration’s budget. Any day now, the House of Representatives is expected to vote on a spending bill outlining funding for the agency through the next fiscal year.

Since his first day in office, President Biden has pledged to make environmental justice a cornerstone of his policy agenda. In May, EPA Administrator Michael Regan and Attorney General Merrick Garland unveiled a new enforcement strategy outlining how their agencies would work together to help fulfill that pledge and pursue environmental justice.

“Communities of color, Indigenous communities, and low-income communities often bear the brunt of the harm caused by environmental crime, pollution, and climate change,” Garland said during a press conference. “We will prioritize the cases that will have the greatest impact on the communities most overburdened by environmental harm.”

But it isn’t enough to just better prioritize cases, says Eric Schaeffer, executive director of the Environmental Integrity Project and a former director of the EPA’s Office of Civil Enforcement.

“Many if not most EPA enforcement actions are already brought against polluters surrounded by lower-income neighborhoods or communities of color, since that’s where the biggest polluters are concentrated,” Schaeffer said. “The problem is that there aren’t nearly enough of them, they take longer than they should, and they sometimes aren’t significant enough to make a long-term difference.”

“That won’t be solved by continually refining targeting strategies for an ever-shrinking number of cases,” he said. Instead, the enforcement division needs to conduct more investigations and bring more cases when they find violations. And to do that, they need adequate funding and staff.

The Biden administration’s proposed budget allocates over $630 million for enforcement — an 11 percent increase from last year when adjusted for inflation, but still significantly less than in 2011, when enforcement expenditures were nearly $730 million. Biden also wants to boost the division’s staff by more than 130 — which would still leave the division about 600 shy of the nearly 3,300 employees it had a decade ago.

“It’s a start,” said Schaeffer. He’d like to see a bigger investment, but “we live in the real world, and we’ve got a fifty-fifty Senate,” he said.

Once the House passes legislation to fund the EPA, they will still have to iron out any differences between their version and the Senate’s version, which lawmakers say they’ll release before the end of the month. Then both chambers will need to pass the final version of the bill, which likely won’t happen until after the election in November.

“The administration is trying to reorient its focus, but it needs the tools to do that,” said Tim Whitehouse, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and a former senior attorney for EPA’s enforcement division. “It needs the enforcement officers, it needs the inspectors, it needs the attorneys to make sure that there is environmental justice in this country.”

But building the division back up won’t be easy. “Just on a human level, you know, it takes time,” Whitehouse said. “These are very complicated laws and regulations. And so EPA needs to make sure it has the best available people and the proper expertise to see these enforcement cases through from beginning to end.”

For more than a decade, conservatives who see the EPA’s enforcement efforts as overreach have successfully whittled away funding and staffing for the enforcement division. That came to a head under the Trump administration. In 2017, the Washington Post wrote that former President Trump was planning “to take a sledgehammer” to the agency, attempting to cut enforcement funding by 60 percent.

Whitehouse thinks it will take several years of sustained funding to get the enforcement division back to a place where it can adequately enforce the country’s environmental laws. “It’s pretty easy to break something,” he said. “It’s really hard to put it back together.”