In the wake of the East Palestine, Ohio train derailment, Governor Mike DeWine called on Congress to look into why the rural village didn’t know ahead of time they had volatile chemicals coming through town.

“We should know when we have trains carrying hazardous materials through the state of Ohio,” DeWine said at a press conference.

This information is out there, but it’s probably not what the governor had in mind. With the derailment of the Norfolk Southern train receiving international attention, more railroad communities are now asking what is traveling through their backyard.

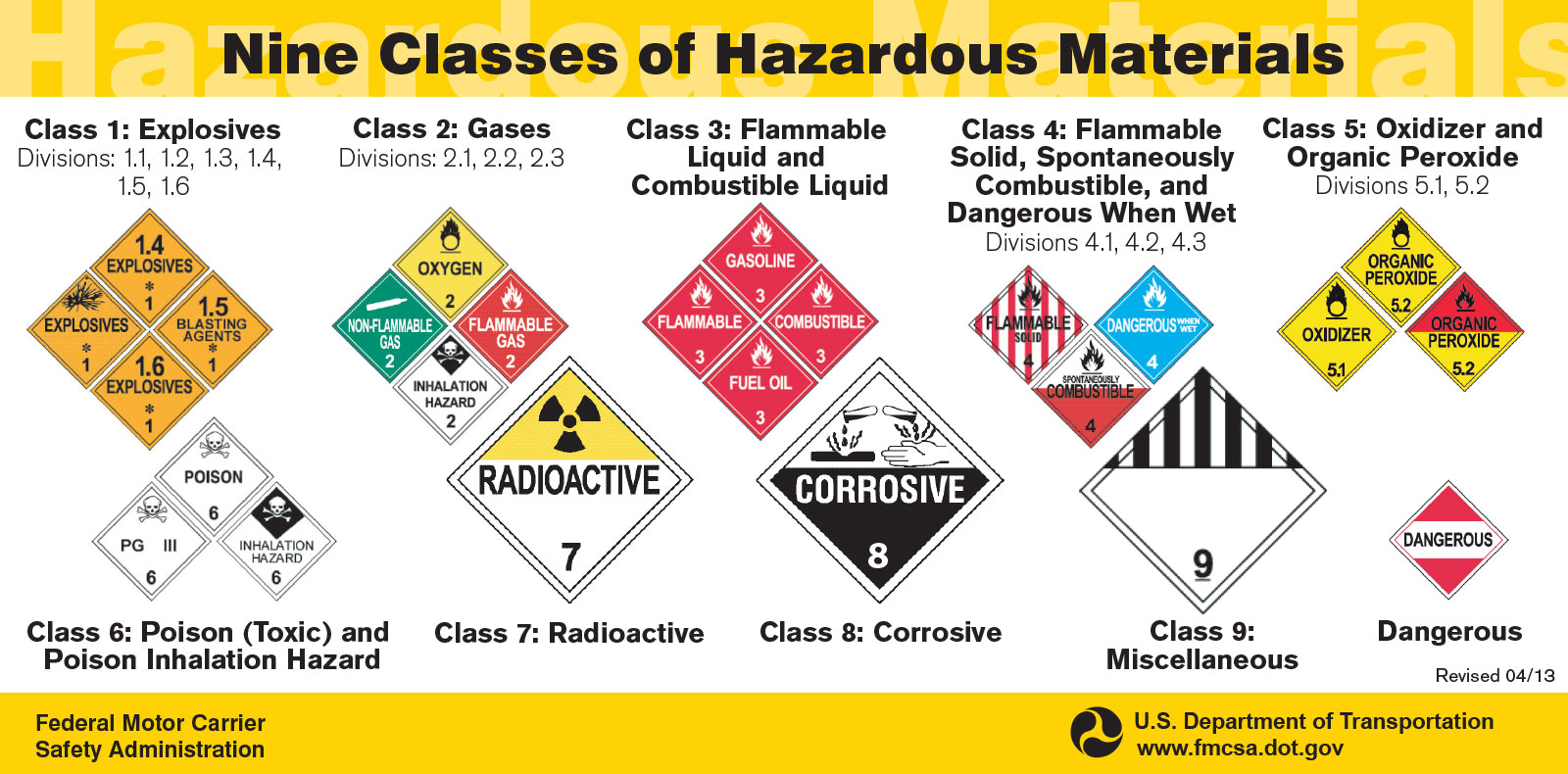

According to representatives from the United States Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, or PHMSA, all trains that carry hazardous materials are subject to “hazard communication” requirements. But this doesn’t mean a rail company tells the residents what is going by their town every day.

The troika of hazard communications, according to the agency, contains the following: There is a listing of all cars with hazardous material on each train; signage detailing which car is carrying what material; and the use of AskRail, an electronic application used by first responders that gives up-to-the-minute details on a train’s location and contents.

AskRail was created by the country’s largest railroad companies and first responders and is not made available to the public over concerns of public safety and terrorism. PHMSA told Grist that all major railroad companies, including Norfolk Southern, use this application and the agency is developing a proposal to make the use of this app mandatory and expand its use to smaller railroad companies as well.

In 2017, when New Jersey citizens and politicians demanded more transparency about the contents and schedules of trains moving through their state, in the wake of national attention focused on oil-by-rail trains, a former managing director of the National Transportation Safety Board called it a “dumb idea.”

“Nobody cares, frankly, until there’s a huge event,” a former railroad industry employee, who would only talk on background, told Grist. “Nobody cares outside the railroad industry, they care because it’s their liability and personnel handling materials.”

Nick Messenger is a senior researcher with the nonprofit Appalachian policy think tank Ohio River Valley Institute. He told Grist that however a material is deemed hazardous should be part of a transparent process and that the people who live in rail communities should get a say in that labeling.

“These places already kind of feel forgotten or overlooked and we’ve run railroads through their communities,” Messenger said. “When I think of one car spilling and polluting water, soil, or air, that’s a hazard.”

Justin Mikulka, author of Bomb Trains: How Industry Greed and Regulatory Failure Put the Public at Risk, told Grist that the rhetoric around the threat of terrorism and a community’s right to know has been a flashpoint in the rail industry. He said the industry’s offer of information and self-regulation is a means to prevent government regulation.

“‘Don’t regulate us, we will volunteer to do the right thing,’” he said. “Historically, that’s always been their first offer.”

Michael F. Gorman is an operations management professor at the University of Dayton’s School of Business who has worked for decades as a consultant in the railroad industry. He said that providing the general public with this advance notice of information, be it a rail car or a tractor-trailer, wouldn’t be an excessive cost to shipping companies, but the deluge of information wouldn’t have any economic benefit or preventive value.

“What would East Palestine, Ohio, have done if they knew there was a train coming with vinyl chloride? The answer is maybe the first time they find out they throw rocks at the train or have signs or hold up a protest or something, but they can’t stop moving hazardous material,” Gorman said.

Railroads carry a lot of hazards. According to the Association of American Railroads, freight railroads moved 2.2 million carloads of plastics, fertilizers and other chemicals in 2021. The majority of these chemicals were ethanol, but also include chemicals used in the plastics industries, industrial production, and agriculture.

These hazards have become integral components of modern life. But they come at a price.

Fossil fuels comprise the building blocks of plastics manufacturing. So as demand for oil and gas decreases worldwide, many fossil fuel companies are turning their attention to the plastics industry to sustain their production. It’s estimated that global plastic production will quadruple by 2050, reinforcing a need for the movement of these chemicals to and from petrochemical production plants, with trains moving these hazards daily through railroad towns like East Palestine.

As Gorman pointed out in a column for the online news site The Conversation, rail is not the only way these hazards get around. The trucking industry is also a major mover of hazardous chemicals. Just like when a train derails, or when a truck flips over on the highway, first responders are made aware of what is inside by reading the signage on the outside of the truck, as well as a manifest on the inside. Two weeks ago, a truck containing nitric acid, a toxic gas used to make fertilizer, flipped over in Tucson, Arizona, killing the driver, and prompting shelter-in-place notices for residents due to the public health risks.

‘It’s a fact of life, you can’t eliminate hazmat materials,” Gorman said. “It’s a negative side effect of progress quite frankly.”

Stephanie Herron, a national organizer with the collective Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform said in a statement that neighboring communities refuse to accept these events as a fact of life.

“These issues aren’t new to the people who live near hazardous facilities who have been speaking up about the urgent need to transition to safer chemicals to prevent disasters in their communities,“ Herron said. “What’s new is that more people are paying attention.”

When a train carrying crude oil derails or a truck filled with toxic chemicals skids off the road, first responders are on the scene. Eric Brewer is the director of emergency services and chief of the hazardous response team for Beaver County, Pennsylvania, which borders East Palestine, Ohio.

He was there roughly 30 minutes after a 150-car train derailed in neighboring East Palestine late at night on February 3, now thought to be caused by an overheating wheel bearing. He said first responders that night used the electronic application AskRail to determine what was aboard the Norfolk Southern train, but agencies don’t often get notice ahead of time when hazards come through their communities. Brewer said many of the agencies he works with are volunteer firefighters, who don’t have the resources to get detailed training for responding to hazardous situations.

“There are no laws for prenotification to first responders, so we assume that all rail cars are hazardous,” Brewer told Grist.

The only trains that require prenotification to a community’s first responders are known as “high-hazardous flammable trains,” or HHFTS. These trains are long units filled with 20 or more tankers of flammable liquids such as ethanol or oil, often dubbed “bomb trains” by those inside the rail industry.

Representatives with PHMSA told Grist that railroads are required to inform state emergency responders of the routes that HHFTS travel. In response to the East Palestine derailment, the federal Department of Transportation is calling for a renewed push for notifying communities when HHFTs are coming through their communities.

The train that derailed in East Palestine was not an HHFT and this federal push for increased notification would have not changed the February 3 disaster.

Despite what federal agencies say and want, Brewer told Grist that his agency doesn’t receive pre-notification when these high-hazard trains roll through. Similarly, Ohio fire officials told a local news station that firefighters often don’t know they are walking into a hazardous situation.

The night of the fiery crash, Brewer said the first responders went to work inspecting the damage, but it is often hard to discern what a placard is supposed to say when a tanker is engulfed in flames.

He said that it was a joint decision between the Ohio emergency responders, his agency, and Norfolk Southern officials on the scene to let the tankers filled with vinyl chloride burn. The gas, which is a carcinogen, has garnered national attention after its controlled burn left a massive black cloud over the town and caused an eventual evacuation and lingering health concerns.

Despite any information they did have ahead of time, the placards on the train, and the use of AskRail, the tankers burned for hours. The decision to let train cars filled with toxic chemicals burn comes at the recommendation of the federal agency that regulates the movement of hazardous materials.

According to the PHMSA’s publicly available 2020 Emergency Response Guidebook, when first responders are met with tankers of flammable gas like vinyl chloride they are to evacuate the area within a one-mile radius, stay away from tanks engulfed in flames, and when a massive blaze can’t be put out with an unmanned nozzle, withdraw from the area and “let fire burn.”