This article was produced in partnership with The Intercept.

A new business model for breaking down environmental movements was being hatched in real time. On Labor Day weekend of 2016, private security dogs in North Dakota attacked pipeline opponents led by members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe as they approached earth-moving equipment. The tribal members considered the land sacred, and the heavy equipment was breaking ground to build the Dakota Access Pipeline. With a major public relations crisis on its hands, the pipeline’s parent company, Energy Transfer, hired the firm TigerSwan to revamp its security strategy.

By October, TigerSwan, founded by James Reese, a retired commander of the elite special operations Army unit Delta Force, had established a military-style pipeline security strategy.

There was one nagging problem that threatened to unravel it all: Reese hadn’t acquired a security license from the North Dakota Private Investigation and Security Board. Although Reese claimed TigerSwan wasn’t conducting security services at all, the state regulator insisted that its operations were unlawful without a license.

TigerSwan turned to Jonathan Thompson, the head of the National Sheriffs’ Association, a trade group representing sheriffs, for help. The security board “has a problem understanding and staying within their charter,” Shawn Sweeney, TigerSwan’s senior vice president, wrote to Thompson. If he could “discuss possible political measures to apply pressure it will assist in the entire project success [sic],” the employee appealed.

Thompson was enthused to work with TigerSwan. “We are keen to be a strong partner where we can help keep the message narrative supportive,” he wrote back. “[C]all if ever need anything.”

Despite Thompson’s offer of assistance, TigerSwan continued to operate in North Dakota with no license for months. The company managed dozens of on-the-ground security guards, surveilled and infiltrated protesters, and passed along profiles of so-called “persons of interest” to one of the largest midstream energy companies in North America.

The revelation of TigerSwan’s close working relationship with the National Sheriffs’ Association is drawn from more than 50,000 pages of documents obtained by The Intercept through a public records request to the North Dakota Private Investigation and Security Board. In 2017, the board sued TigerSwan for providing security services without a license. The state eventually sought a $2 million dollar fine through the administrative process, but Tigerswan negotiated a $175,000 fine instead — well below standard fines for such activities.

A discovery request filed as part of the case forced thousands of new internal TigerSwan documents into the public record. Energy Transfer’s lawyers fought for nearly two years to keep the documents secret, until North Dakota’s Supreme Court ruled in 2022 that the material falls under the state’s open records statute. Because an arrangement between North Dakota and Energy Transfer allows the fossil fuel company to weigh in on which documents should be redacted, the state has yet to release over 9,000 disputed pages containing material that Energy Transfer is, for now at least, fighting to keep out of the public eye.

The released documents provide startling new details about how TigerSwan used social media monitoring, aerial surveillance, radio eavesdropping, undercover personnel, and subscription-based records databases to build watch lists and dossiers on Indigenous activists and environmental organizations.

At times the pipeline security company shared this information with law enforcement. In other cases, WhatsApp chats and emails confirm Tigerswan used what it gathered to follow pipeline opponents in their cars and develop propaganda campaigns online. The documents contain records of TigerSwan attempting to help Energy Transfer build a legal case against pipeline opponents, known as water protectors, using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, a law that was passed to prosecute the mob.

The Intercept and Grist contacted TigerSwan, Energy Transfer, the National Sheriffs’ Association, as well as Thompson, the group’s executive director. None of them responded to requests for comment.

To TigerSwan, the emergence of Indigenous-led social movements to keep oil and gas in the ground represented a business opportunity. Reese anticipated new demand from the fossil fuel industry for strategies to undermine the network of activists his company had so carefully gathered information on. In the records, TigerSwan expressed its ambitions to repurpose these detailed records to position themselves as experts in managing pipeline protests. The company created marketing materials pitching work to at least two other energy companies building controversial oil and gas infrastructure, the records show. TigerSwan, which was staffed heavily with former members of military special operations units, branded its tactics as a “counterinsurgency approach,” drawing directly from its leaders’ experiences fighting the so-called War on Terror abroad.

TigerSwan did not just work in North Dakota. Energy Transfer hired the company to provide security to its Rover Pipeline in Ohio and West Virginia, the documents confirm. By spring 2017, TigerSwan was also assembling intelligence reports on opponents of Energy Transfer and Sunoco’s Mariner East 2 Pipeline in Pennsylvania.

The documents from the North Dakota security board paint a detailed picture of counterinsurgency-style strategies for defeating opponents of oil and gas development, a War-on-Terror security firm’s aspirations to replicate its deceptive tactics far beyond the Northern Great Plains, and the cozy relationship between businesses linked to the fossil fuel industry and one of the largest law enforcement trade associations in the U.S. The impetus for spying was not simply to keep people safe, but to drum up profits from energy clients and to allow fossil fuels to continue flowing, at the expense of the communities fighting for clean water and a healthy climate.

“For them, it was an opportunity to help create a narrative against our tribe and our supporters,” said Wasté Win Young, a citizen of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and the one of the plaintiffs in a class action civil rights lawsuit against TigerSwan and local law enforcement. Young’s social media posts repeatedly showed up in the documents. “We weren’t motivated by money or payoffs or anything like that. We just wanted to protect our homelands.”

The Intercept published the first detailed descriptions of TigerSwan’s tactics in 2017, based on internal documents leaked by a TigerSwan contractor. Nearly six years later, there have been no public indications that the security company obtained major new fossil fuel company contracts. Meanwhile, corporate lobbyists spurred the passage of so-called “critical infrastructure” laws widely understood to stifle fossil fuel protests in 19 states across the U.S. Collaborations between corporations and law enforcement against environmental defenders have proliferated, from Minnesota’s lake country to the urban forests of Atlanta.

No significant regulatory reforms have been enacted to prevent firms from repeating counterinsurgency-style tactics. And TigerSwan is far from the only firm to use invasive surveillance strategies. The North Dakota documents show that at least one other private security firm at Standing Rock appears to have utilized similar schemes against pipeline opponents.

“We need to always be very clear that the industry knows what a risk the climate movement is,” said May Boeve, the executive director of 350.org, a climate nonprofit that was repeatedly mentioned in TigerSwan’s marketing and surveillance material. “They’re going to keep using these kinds of strategies, but they’ll think of other things as well.”

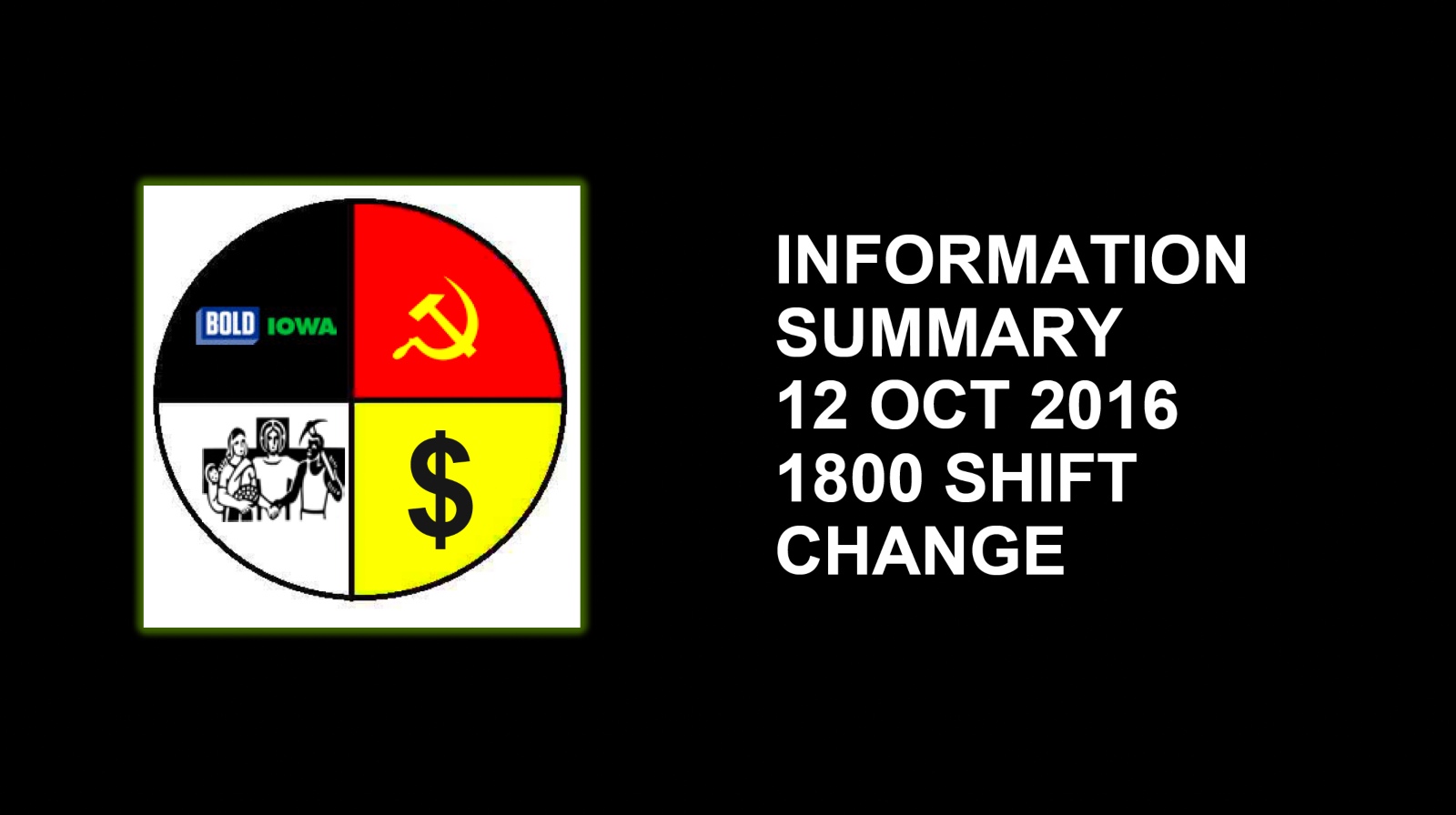

Left: TigerSwan adapted an image of a medicine wheel, a symbol of spiritual significance to many Native peoples, to frame symbols of entities they believed to be influencing water protectors: communism, nonprofits, money, and the Catholic Worker movement. Right: This image from a TigerSwan “Daily Intelligence Update” presentation from January 2017 appears to depict TigerSwan personnel at work.

TigerSwan’s aspirations

“Gentlemen, as you are aware there has been a shift in environmentalist and ‘First Nations’ groups regarding the tactics being used to prevent, deter, or interrupt the oil and gas industry,” said a February 2017 email drafted by TigerSwan employees to a regional official at ConocoPhillips, a major oil and gas producer — and a potential Tigerswan client.

“Recently in our area the situation has become extremely tense with ‘protestors’ using terrorist style tactics which are well beyond simple civil disobedience,” the email continued. “If steps have not already been taken to prevent and plans to mitigate [sic] an event or events like these to Conoco I may be able to suggest some solutions.”

TigerSwan’s marketing materials read like a playbook for undermining grassroots resistance. ConocoPhillips was just one of the companies the private security firm had in its sights.

In another case, a PowerPoint presentation drafted for Dominion, which was building the Atlantic Coast natural gas pipeline through three mid-Atlantic states, offered detailed profiles of local anti-pipeline groups and individuals identified as “threat actors.” (The planned pipeline was canceled in 2020.) TigerSwan laid out the types of services it could provide, including a “Law Enforcement Liaison” and access to GuardianAngel, its GPS and mapping tool. (Neither ConocoPhillips nor Dominion responded to questions about whether they hired the security firm.)

In January 2017, a TigerSwan deputy program manager emailed a presentation titled “Pipeline Opposition Model” to Reese and others, explaining that it was meant to serve as a business development tool and a “working concept to discuss the problem.” The presentation claimed external forces had helped drive the Standing Rock movement and pointed to outside tribes, climate nonprofits like 350.org, and even billionaires like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, who had a “vested interest in DAPL failure” because of their investments in the rail industry.

Water protectors used an elaborate set of social movement theories to advance their cause, another slide hypothesized, including “Lone Wolf terror tactics.” Specifically, TigerSwan speculated that pipeline opponents could be using the “hero cycle” narrative, a storytelling archetype, to recruit new movement members on social media and energize them to take action — a strategy, the presentation said, also used by ISIS recruiters.

Anyone whose work had touched the Standing Rock movement could become a villain in TigerSwan’s sales pitches. One PowerPoint presentation included biographical details about Zahra Hirji, a journalist who worked at the time for Inside Climate News. Another included a photo of a water protector’s former professor and her course list.

As a remedy, the company offered up a suite of “TigerSwan Solutions.” To the security firm, keeping the fossil fuel industry safe didn’t just mean drones, social media monitoring, HUMINT (short for human intelligence, such as from undercover personnel), and liaising with law enforcement — all included on its list — it also meant local community engagement, counter-protesters, building a “pipeline narrative,” and partnering with university oil and gas programs.

“Win the populace, and you win the fight,” the presentation stated, repeating a key principle of counterinsurgency strategy.

Reese approved. “I’d like to have these cleaned up and branded so I can use,” he wrote back.

Reese used similar material to shore up his relationship with existing clients. In December 2016, he requested a copy of a presentation titled “Strategic Overview,” which he hoped to send to Energy Transfer supervisors working on building the Rover natural gas pipeline. The presentation, a version of which The Intercept previously published, draws heavily from a 2014 report by the Republican minority staff of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, claiming that a “club” of billionaires control the environmental movement.

In a memo called “The Standing Rock Effect,” Tigerswan lays out a set of seven criteria the company had developed for identifying anti-pipeline camps sprouting up across the country. “TigerSwan’s full suite of security offerings offsets the risk these camps pose to a company’s bottom line,” the company concluded.

Tigerswan utilized its promotional materials to target both energy companies and states with oil and gas resources. In April 2017, the security firm and the National Sheriffs’ Association planned to brief more than 50 state employees in Nebraska, including staffers in the governor’s office, the state Emergency Management Agency, and the State Patrol, on the “lessons learned” from the Dakota Access Pipeline protests. A contractor for the National Sheriffs’ Association wrote that the briefing was in part “to prepare the state of Nebraska for the Keystone Pipeline issues coming in months ahead.”

Targeting water protectors

TigerSwan’s obsessive tracking of environmental activists is laid out in detail in the North Dakota documents. Assisted at times by National Sheriffs’ Association personnel, the company targeted little-known water protectors, national non-profits, and even legal workers.

The first page of a template for intelligence sharing encouraged TigerSwan employees to enter information about any “New Person of Interest.” TigerSwan personnel routinely referred to its targets as “EREs,” short for Environmental Rights Extremists, apparently a version of the Department of Homeland Security’s classification of “Animal Rights/Environmental Violent Extremist” as one of five domestic terrorism threat categories.

A document labeled “Background Investigation: 350.org” helps explain why the company kept tabs on a national environmental organization with little visible presence on the ground at Standing Rock. Using an “Influence Rating Matrix,” TigerSwan ranked 350.org’s “formal position in organization/movement” and its “criminal history” as “0” — but gave its highest rating of “5” to the group’s size, funding, online presence, and history with similar movements.

TigerSwan also attempted to dig up dirt on legal workers with the Water Protector Legal Collective, which represented pipeline opponents. The security company used the CLEAR database, which is only available to select entities like law enforcement and licensed private security companies, to dig up information on attorney Chad Nodland. The company concluded that Nodland was also representing a regional electric cooperative that generates some of its power through wind — apparently considered a rival energy source to the oil the Dakota Access Pipeline would carry. (Nodland told The Intercept and Grist he never worked for the cooperative.) TigerSwan also put together a whole PowerPoint presentation on Joseph Haythorn, who also worked for the legal collective and submitted bail money for clients to be released.

At the same time, the National Sheriffs’ Association was building its own profiles and sharing them with TigerSwan. In one instance, a contractor for the sheriffs’ group passed along a six-page backgrounder on LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, a prominent Dakota Access Pipeline opponent and historian, to TigerSwan. The document included statements Allard made to the press, her public appearances, social media posts, and details about tax liens filed against her and her husband.

Targeting individual pipeline opponents like Allard seems to have been part of TigerSwan’s strategy particularly when it needed to have something to show its client, Energy Transfer Partners. In one exchange with employees, Reese suggested digging up more intelligence on a pipeline opponent who goes by the mononym Tawasi.

“We need to start going after Tawasi as fast as we can over the next couple weeks so we can show some more stuff to ETP,” Reese wrote, using an abbreviation for the company’s old name, Energy Transfer Partners. The documents show that TigerSwan kept close tabs on Tawasi, reporting his movements in daily situation reports, monitoring his social media, and at one point noting that he had gotten a haircut.

Tawasi, who had a large social media following but was not a prominent leader of the anti-pipeline movement, was bewildered that he had been so closely monitored. “They didn’t have anything at all,” he told The Intercept and Grist. “And they picked me as somebody that they thought they could make something out of.”

“It makes me feel unsafe,” he said, “because the same contractors could be working for a different company, still following me around under a different contract from the next oil company down the line.”

Prairie McLaughlin, Allard’s daughter, said records of TigerSwan’s activities remain important, even six years later. “It matters because it gives somebody a handbook on what could happen — what might happen.”

Not a ‘Mercenary Organization’

After The Intercept published its first set of leaked TigerSwan documents in 2017, the company attempted to downplay the impact of the revelations. In a memo, TigerSwan shrugged off the story’s importance. “The near-term impact of the article is positive for the company,” TigerSwan claimed. The revelations had caused water protectors to limit their social media activity, rendering them “incapable of effectively recruiting members, raising operational funding, or proselytizing,” TigerSwan wrote.

The company intended to use “information operations” to maintain the paranoia: “This looking over-their-shoulder behavior will continue for several months because of internal suspicions and targeted information operations.”

Internally, the company scrambled to mount a public relations response, calling on help from Chris LaCivita, a Republican political consultant now reportedly being considered for a senior role in Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign. A memo emailed to LaCivita by TigerSwan’s external affairs director said that, as a defensive strategy, the company would assert on background that “TigerSwan is not a ‘mercenary organization.’” It was a point that must never be made on the record, the document says, because it “would be like saying ‘no I don’t beat my wife.’” (LaCivita did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

TigerSwan’s offensive strategy primarily consisted of trying to marshal evidence showing that water protectors were violent lawbreakers, professional protesters, un-American, and not even very Indigenous. The document author advised TigerSwan to locate “Any visuals, video of demonstrators waving flags or using insignia of an enemy of the United States.” Another suggested talking point said, “Upon our arrival, we quickly learned that a vast majority of the protestors were not indigenous not [sic] part of the peaceful water movement.”

In a final act of law enforcement collaboration, the memo advised TigerSwan to identify one local and one federal law enforcement source that could defend them — but only off the record.

Outside the public relations strategy, TigerSwan didn’t dramatically shift its tactics in response to the story, the documents suggest. In an email dated June 20, 2017, nearly a month after The Intercept’s first exposé, an intelligence analyst distributed a list of anti-pipeline camps across South Dakota, where the Keystone XL pipeline was supposed to be built.

“Maybe your folks can take a look at the list, check the social media for the sites, and figure out if A) you can get in and B) if there’s value to being inside and C) do you have the creds you need to get in. If you figure out that you need to attend some more events to build cred and access we can do that,” he said. “That should feed the beast until the next shiny thing.”