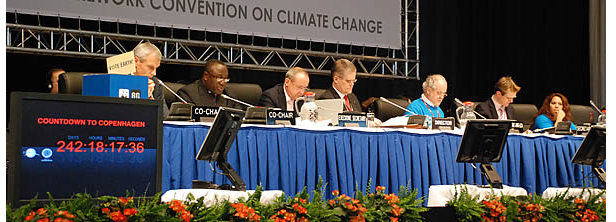

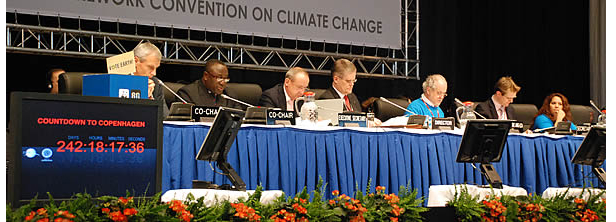

The “Countdown to Copenhagen” clock was front and center at the Bonn climate talks last month.Courtesy UNFCC

The “Countdown to Copenhagen” clock was front and center at the Bonn climate talks last month.Courtesy UNFCC

I suppose what happened to the ticking clock says all we need to know about the state of the make-or-break international negotiations on combating climate change.

The bright red digital timepiece was affixed to the podium for the first round of the talks so far this year, held in Bonn during the two weeks running up to Easter. Boldly labelled “Countdown to Copenhagen,” it ticked off the days, hours, minutes and seconds to the start of the vital meeting in the Danish capital, widely billed as the last chance to strike a deal to stop global warming from running out of control.

It was supposed to bring a sense of urgency to the talks, which over the last years have progressed at a pace that would make a snail resemble Speedy Gonzales. And not convinced that the sight of the changing numbers alone would be enough to impress the delegates from more than 190 nations, the NGOs at the meeting persuaded the conference secretariat to add an audible “tick-tock.” The sound had to be turned off when the speeches began, but it was there at the beginning of every session — making the point that time was running out.

Well, it was for the first few days anyway, at the stage when things were going relatively well, such as when Todd Stern, the new U.S. climate change envoy told the meeting that the Obama administration was “seized with the urgency of the task before us.” But the talks soon returned to their normal torpor, and delegates insisted that the clock’s ticking be turned off. It was “irritating,” they complained, and no doubt they did indeed find it annoying to be reminded that time was flying by in the real world outside the conference hall.

In a sense, they succeeded not merely in silencing the clock, but in stopping it altogether. True, the red digits went on flickering downwards, but after the ten days of talks things were no further forward than they had been at the end of last year when George W. Bush’s team was still representing the United States. The only substantial agreement was to draw up negotiating texts to be discussed during the next round, again in Bonn, at the beginning of July. In other words, enough was done to stop the talks from collapsing, but not nearly enough to move them in any way forward.

Rich and poor countries ended as far apart as ever on targets for cutting emissions. Developing countries said they wanted industrialized ones to slash them by 40 percent from 1990 levels by 2020, with the poorest nations and small island states pushing for 45 percent. But nothing like this is on the horizon. The United States has only expressed an aspiration to get back to 1990 levels by then; Canada expects them to be 24 percent higher.

Only Europe is anywhere near being on the same page as the developing countries. EU nation agreed two years ago on a 20 percent cut, rising to 30 percent if other industrialized countries took strong enough action. But that was two years ago and — though the commitment remains — Europe’s enthusiasm for deep cuts in emissions has since distinctly cooled, even as increasing evidence of accelerating climate change demonstrates that much tougher measures will actually be needed.

In fact, it was Europe that effectively condemned the Bonn talks to futility when its leaders decided, just a week before the meeting began, not to say how much money they were prepared to provide to help developing countries cut their emissions. They have long accepted, as increasingly does the United States, that large sums will be needed and have promised in principle to provide them. But the EU decided to sit on its hands until other nations revealed what they would commit.

The problem is that the money is the key to breaking the climate deadlock. Until rich nations start delivering on their promises to provide serious funds, developing ones will not start talking about what they will do to restrain their emissions and, in turn, industrialized ones will not consider tougher targets. The EU leaders are not due reconsider their position on financial commitments until June 18, six days after the next Bonn talks conclude, suggesting that the next international negotiating session will get nowhere either.

The best hopes of a breakthrough now rest with a special climate summit to be held alongside the G8 summit on the island of La Maddalena, Italy, in July. There will be a preparatory meeting in Washington, D.C., in two weeks time, but it will take a top-level breakthrough at the summit to provide the impetus to get serious talks under way.

But by then another three months will have passed, and the countdown, audible or not, will be getting closer and closer to Copenhagen.