The clean energy bill slogging through the U.S. Congress is far weaker than what’s needed. There’s every chance it will a) get weaker still and b) fail to pass in the end. These facts are widely acknowledged among progressives. What’s less agreed upon is who or what is to blame.

You see a lot of stuff like this post on OpenLeft (from Friends of the Earth) that casts the bill’s weakness as a failure of will by progressive senators. What’s needed is for some senate “champions” to “stand up for a stronger bill.” Similarly, many folks have traced the bill’s failures back to Obama, saying he’s been distracted by health care and insufficiently engaged. The idea seems to be that the bill would be better if only those damn Democrats would try harder.

But the lack of vocal Democratic champions for a stronger bill is more effect than cause. The root of America’s political dysfunction lies elsewhere, and deserves far more attention, not only from leftie activists but from Democrats themselves and the mainstream press.

What’s that dysfunction? It’s simple: a supermajority requirement coupled with an extreme, unified minority. Everything else — and I mean pretty much every lamentable feature of American politics — flows out of that. Rich Yeselson puts it in pungent terms: “We are living through the Californiafication of America–a country in which the combination of a determined minority and a procedural supermajority legislative requirement makes it impossible to rationally address public policy challenges.”

Yes, this is a discussion about congressional procedure, which conventional wisdom says will bore everyone. But it’s time you got un-bored, and quick, because nothing else you care about is going to improve until this does.

The stupormajority

First, let’s talk about the supermajority requirement. In the Senate, any senator can continue debating forever and prevent a bill from going to the floor for a vote — that’s the filibuster. In 1917, a new rule was instituted allowing the filibuster to be overcome by a “cloture vote,” which would end debate and move the bill forward. Originally cloture votes required 67 senators, but in the mid-’70s it was changed to 60.

In the popular imagination, filibusters involve legislators camped out on the floor of the Senate, reading the Constitution aloud, struggling to stay awake for days on end. But it’s not like that any more. Norm Ornstein describes what happened in his stellar piece, “Our Broken Senate“:

… after the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the filibuster began to change as Senate leaders tried to make their colleagues’ lives easier and move the agenda along; no longer would there be days or weeks of round-the-clock sessions, but instead simple votes periodically on cloture motions to get to the number to break the log-jam, while other business carried on as usual.

As so often happens, the unintended consequences of a well-intentioned move took over; instead of expediting business, the change in practice meant an increase in filibusters because it became so much easier to raise the bar to 60 or more, with no 12- or 24-hour marathon speeches required.

Since any senator could raise the threshold required to pass a bill from 51 votes — the majority requirement envisioned by the Founders — to 60 with no particular effort, more them started doing it.

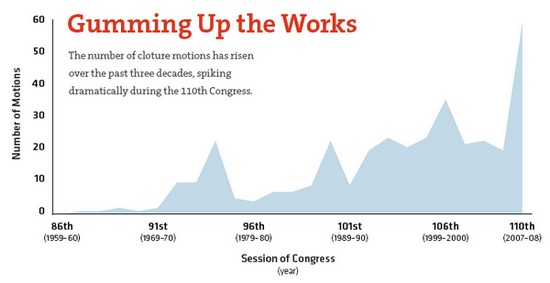

But something’s changed even more in the last few years. Here’s Ornstein’s chart:

Graph: The American

Graph: The American

As you can see, today’s Republican minority has taken obstruction to a new level. Sixty votes are now required to do almost anything in the Senate. It’s not unusual for a bill to go through three separate cloture votes before it’s passed.

Step back a moment and appreciate what’s happened: this amounts to an radical change in our constitutional system of governance, drastically increasing the difficulty of passing legislation to address the nation’s challenges. Not only did the country never openly debate it; not only did Congress never vote on it; nobody even talks about it!

It’s a big deal, though. The 60-vote threshold is much, much harder to reach than 51. Democrats happened, through a variety of unusual circumstances, to enter 2009 with a wildly popular, history-making president and (now that Al Franken’s finally in) a 60-vote majority in the Senate. But a majority that size is extremely rare in American politics — Dems last had one back in the ’70s.

You might say, “Well, fine, that just means legislation has to be bipartisan. That’s as it should be.” Which brings us to the extremist minority.

The stuporminority

It’s pretty widely understood that American politics has become more partisan over the last few decades. There’s a long and complex story to be told about it, involving the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the exodus of white Southern voters from the Democratic party, and the ideological clarification of both parties in ensuing decades … but we won’t get into that here. (Increasing partisanship is constantly and unctuously lamented, but I tend to think it’s inevitable, appropriate, and in many ways even salutary. Again, though, that’s another conversation.)

History aside, let’s acknowledge the obvious: at the federal congressional level, the Republican Party has become tight in its discipline, extreme in its ideology, and utterly unprincipled in its tactics. Political journalists and analysts in the U.S. are supposed to portray the parties as mirror images — “both sides do it” is a mark of Savvy and Seriousness for some reason — but to understand today’s situation it’s crucial to understand that they are not. Congressional Republicans exercise far more party discipline, are far more extreme ideologically, and are far more willing to twist and abuse procedure than are congressional Democrats.

The sole goal of today’s Republican minority is to insure that Democrats fail to accomplish anything; that’s been clear since the day they became a minority in 2006. Exceptions to the rule are increasingly rare. Sen. John Warner (Va.) retired; Sen. Arlen Specter (Penn.) was driven out of the party. There are the two Mainers, Sens. Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins. John McCain (Ariz.) crosses the aisle occasionally, for idiosyncratic and largely ego-related reasons. Dick Lugar (Ind.) sometimes, especially on foreign affairs. Lindsey Graham (S.C.) is sniffing around the broker role. But by and large, the “Republican moderate” is all but extinct in the U.S. Congress.

With all but maybe one or two Republican votes off the table, the conservative end of the Democratic caucus — generally senators representing low-population states — take on unprecedented, near-total power. Ben Nelson (Neb.) gets to whack a few hundred billion off the stimulus package (sacrificing thousands of jobs) just because he feels like it. Max Baucus (Mont.) can sit astride the health-care reform process for months, noodling with Republicans (who of course end up offering him zero votes) to reduce subsidies for the uninsured. Whatever shape the Kerry-Boxer bill ends up taking, it’s certain that Kent Conrad (ND) will get everything he wants from it and more.

Bitter conclusion

Want to know why Sens. Barbara Boxer (Calif.) and John Kerry (Mass.) can’t say enough adulatory things about coal and nuclear and offshore oil drilling? Want to know why billions in pollution allowance value are being dumped on the nation’s dirtiest utilities? Want to know why there are enough agricultural offsets in the bill to make every Big Ag exec rich and help every coal plant avoid the work of reducing emissions for 10 to 15 years? Want to know why a carbon tax would end up with all the same flaws? This is why.

Pick your crappy part of the bill. It’s there because Kerry and Boxer have to get 60 votes and Republicans won’t give them more than a tiny handful, so collecting votes means shoveling handouts to conservative Democrats in hock to the nation’s dirtiest industries.

Want a better bill? Imagine what Kerry and Boxer could put together if they could blow off Nelson and Rockefeller, Conrad and Bayh, Landrieu and Lincoln. Imagine if they only needed a majority, the way legislative bodies in other developed democracies are run; the way the Founding Fathers envisioned our democracy being run; the way common f*cking sense plainly tells us a democracy ought to be run.

Back in 1994, even before today’s unprecedented wave of filibuster threats, a scrappy freshman Senator said:

[People] are fed up — frustrated and fed up and angry about the way in which our government does not work, about the way in which we come down here and get into a lot of political games and seem to — partisan tugs of war and forget why we’re here, which is to serve the American people. And I think the filibuster has become not only in reality an obstacle to accomplishment here, but also a symbol of a lot that ails Washington today.

That was Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.) … who is now threatening to filibuster the health care reform bill.

None of this should be taken as letting anyone off the hook. Everyone — Obama, every senator, and every citizen — ought to be doing everything he or she can to produce the best bill possible. But the “best bill possible” just isn’t very good. The reasons for that are ultimately structural and, yes, procedural. Until Democrats get it together and create a popular push to abolish this anachronistic, profoundly anti-democratic quirk of the U.S. Senate, that’s not going to change, no matter how much willpower is deployed.