When Jay Inslee bowed out of the race for the White House in August, some worried that the Washington governor’s absence would leave a climate-shaped hole in the field. Happily, that fear seems to have been misplaced. Inslee’s six detailed climate proposals, totaling 218 pages, are getting pillaged by some of the remaining candidates with the governor’s blessing. If a Democrat manages to unseat President Trump next year, there’s a good chance that a portion of Inslee’s climate agenda could see the inside of the White House, even if he won’t.

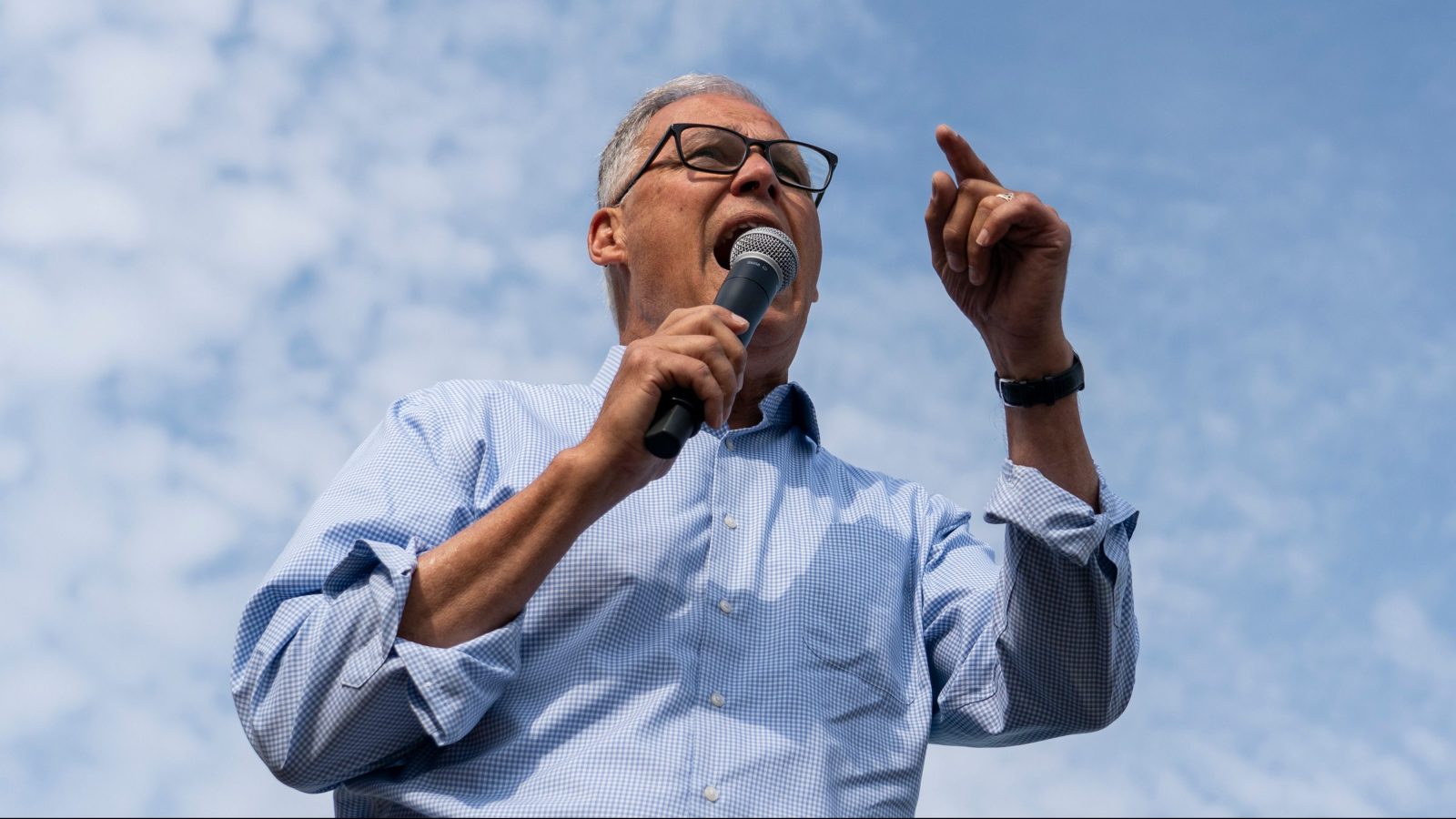

Sam Ricketts

That’s extremely gratifying for Sam Ricketts and Bracken Hendricks, the two masterminds behind Inslee’s plans.

Ricketts, 33, and Hendricks, 52, are both veterans of Insleeworld. Ricketts started out working with then-U.S. Representative Inslee in 2008 on a congressional re-election campaign in Seattle. He followed Inslee to Capitol Hill, serving as executive director of the Congressional Sustainable Energy & Environment Coalition, and then returning with Inslee to Washington state to work on his 2012 gubernatorial campaign.

Hendricks, who founded an early labor and environmental coalition called the Apollo Alliance, linked up with Inslee’s congressional staff in the early aughts. He helped the campaign formulate a green infrastructure bill called the New Apollo Energy Act — the first congressional effort to formulate a comprehensive climate and energy bill. In the course of working together, Hendricks and Inslee discovered they were writing the same book about clean energy. “Literally, we had each written an outline of a book and they were almost identical,” Hendricks said. He decided to co-write the book with Inslee — it became 2007’s Apollo’s Fire — and stayed on as a close advisor.

When Inslee declared his run for the White House in March, both men were already working on the Inslee for America campaign — Ricketts as climate director, and Hendricks in the capacity of senior advisor for climate policy.

Between February and August, Ricketts and Hendricks — with help from Inslee himself, the rest of the campaign team, and a network of outside experts — worked tirelessly to turn a barebones vision for a clean energy economy into a full-fledged platform. I spoke to Hendricks and Ricketts last week to find out how the scrappy team turned a dream into the gold standard of Democratic climate policy.

Our interview has been edited for clarity and condensed for length.

Q. What was your guiding principle as you approached the mammoth job of executing these plans?

A. Hendricks: One thing Governor Inslee was vehement about was that this was a plan to actually do this. He was running everything through a lens of: Is this credible? Can we really do it?

We tried to figure out what the sweet spot was, where you’re not sacrificing ambition, but you’re also not breaking the system by pushing it so hard that it actually ends up slowing you down. Our charge was: What is something that is equal to the science and that rises to the urgency of the climate crisis?

Q. What were the internal debates you had while developing the plans?

a.Hendricks: One strategic piece involved thinking through “What is the role of pricing carbon?” We think that pricing carbon should be part of the solution. And it ended up coming in the context of rolling back fossil fuel subsidies and making polluters pay. We wanted a price on carbon, and we sort of looked at it as a pollution stymie and a way to finance doing good green things. So it’s in there, but it’s subordinated, and it’s at the right level of primacy. Frankly, if you never got it you could still build the rest of the plan, it’s not the linchpin.

Bracken Hendricks

Q. Was there anything you guys had to leave out of the plans?

A.Hendricks: There are two things. Resilience runs through all of it, but I think there could have been a dedicated piece talking about disaster, resilience, risk, and insurance — and how to deal with infrastructure in the context of resilience.

And then I think the last idea is looking back to World War II. FDR had an office of war mobilization, and we spent some time thinking about what would a climate mobilization be and how would you go and move all the pieces of the White House in a really thoughtful way. That’s something we still do hope to get out: some real thought that can be useful to whoever the nominee is.

Q. Are you optimistic that the plans will make their way into the White House in one form or another?

A. Hendricks: Not in a Trump administration.

Ricketts: It’s been gratifying and encouraging to see other candidates reach out to the governor and to us to solicit feedback and input.

Hendricks: Senator Elizabeth Warren picking up that clean energy standard was extremely gratifying. Other campaigns that were really thoughtful in how they were reaching and really testing ideas — Julián Castro and Kamala Harris — those two in addition to Warren stand out.

You can see how environmental justice is getting included in the discussion, how investment at the community level is getting seriously considered, how looking at disparate impacts of pollution is getting seriously considered. There’s just a level of seriousness and ambition that is now the bedrock of the climate strategy.

Q. Are you optimistic that Inslee’s emphasis that climate has to be the No. 1 priority rubbed off on the candidates?

A. Hendricks: I don’t think we’ve fully won on that yet. The governor would say, “if it’s not job one, it won’t get done.” If you look at what President Obama got done, he got health care and the Recovery Act through and then lost the Senate.

The next president’s in for eight years. So they damn well better be a climate president. But this is the window that we have, this really is our moment. If we don’t do it now it won’t get done.

Q. What was the reaction in the Inslee camp when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey unveiled the Green New Deal back in February, right as you were planning Inslee’s climate platform?

A. Hendricks: I’m really glad that there’s a whole fresh group of voices coming in. There are people who’ve been doing incredible work for decades, but I think that the impatience and the urgency of the new generation of activists is an extremely helpful contribution to make sure that we all collectively rise to the challenge, because it is a wartime mobilization. It really is.

Ricketts: It was powerful when the Sunrise Movement sat in the halls of the House leadership in November. From that moment on there has been a galvanization of energy around this. Building a more just and equitable clean energy economy while defeating climate change is not a new concept. It’s one that informed Governor Inslee’s first climate bill 15 years ago and the book that they wrote together. So we were ecstatic about that new energy.

Q. How did you two stay motivated to write basically a book’s worth of climate policy proposals?

A. Hendricks: That sense of urgency, that the next president has to be a climate president, that’s what literally kept Sam and me up at night so that we could write 200 pages of policy. We wanted this out there now, because it’s just not going to matter in the same way in four years.

Ricketts: We would be up taking shifts as we got to crunch time. I would be better late in the night, he would be better getting up earlier, so we would tag out at 2 or 3 a.m. It was a lot of labor writing this much detail and this much thoroughness.

Hendricks: It was a lot of fun, and it was a project of passion. And then we would get to the point where we had enough of a draft and we’d be utterly exhausted and then the whole rest of the team would come into the Google Doc and bring us across the finish line. It was great.