As an artist, Mark Beesley is drawn to subjects that others might find repellant.

Beesley lives only a few miles from the Sizewell nuclear power station in Britain, and has occasionally made the plant the subject of his work. Despite his opposition to nuclear power, Beesley admits to a fascination with the plant’s design. “When you drive by it, you see this semicircular dome looming over the trees,” he says. “It’s a powerful presence.”

Images courtesy REimaginations.

But nukes are nothing compared to one of Beesley’s true obsessions: wind turbines. He paints the emblems of wind power — a form of energy he does support — towering over grazing farm animals and casting long shadows over cultivated land. “My interest in wind turbines as an artist is the actual structures,” he says. “Seen abstractly, as sculptures, they are very beautiful.”

And Beesley’s portrayals of them are popular, at least with some audiences: last week, a wind-industry executive purchased one of his oil paintings at a wind-energy art exhibit in Pittsburgh.

Yes, that’s right, a wind-energy art exhibit. The show — unveiled at a meeting of the American Wind Energy Association and viewable online — is almost certainly the world’s first to have such a focus. By collecting paintings, drawings, posters, and postcards that depict windmills as sleek and simple even as they loom over their natural surroundings, organizer Andrew Perchlik hopes to dispel myths about the aesthetic effects of wind farms on their surroundings.

Perchlik — who is executive director of Renewable Energy Vermont, a trade association promoting wind-farm construction in the state — makes no secret of his industrial aspirations. He created the exhibit to help combat the NIMBY factor vexing developers from Nantucket Sound to the Great Lakes, and hopes to help sway a public that’s under the spell of ad campaigns portraying wind farms as sources of visual pollution. “If people see wind depicted as art, they will intrinsically see it as more beautiful,” he says, adding that he’ll continue accepting new contributions to the online exhibit over the coming year.

There’s no denying that wind farms can dramatically alter oceanfront views, disrupt the shape of mountain ridgelines, and impose themselves on prairie sunsets. Indeed, in many of the pieces in the exhibit, it looks as if someone planted massive metal tubes above rows of lettuce, or erected giant fans to mesmerize merchant marines in shipping lanes. But Perchlik maintains that turbines possess an innate appeal — especially compared to, say, a coal-burning plant.

And the participating artists, who hail from North America, England, Serbia, and Croatia, seem to agree. Most of them did not create their pieces specifically for this exhibit, and many said they’ve long been interested in the clash of industry and nature, whether it plays out in the form of turbines or other technologies.

Contributor Barbara Ekedahl once created a woodblock print of a high-tension power-line tower — which she later sold to an electric company executive. The subject of her art “doesn’t necessarily have to be something I like,” says Ekedahl, who does admit that she would love to get her Vermont home off the grid by erecting a turbine on her property. “It has to be something of interest on the landscape. In that case [the power-line image], I wanted the challenge of carving something with those fine lines.”

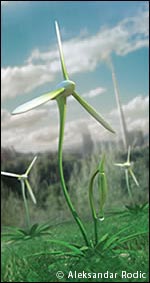

While some may appreciate the bold, industrial visions of Beesley and Ekedahl, those responsible for marketing wind power may favor the exhibit’s “greener” interpretations. Some pieces, such as Anne Subercaseaux’s “Spirit of the Hills,” portray turbines as mere wisps along mountain ridgelines. And Aleksandar Rodic’s “Energy Plant” — one of only two works created specifically for the exhibit — envisions turbines and towers as the bright petals and stems of spring flowers. (The Serbian artist’s painting won first prize in Pittsburgh.)

Mike Gauthier, who contributed a fine-art print to the exhibit, recognizes that wind farms can have an impact on the land, but says he is a bit mystified by the debate raging in his home state of Vermont over plans to build wind farms along ridgelines. “[Wind] has one of the smallest footprints overall,” he says. “It’s far better than digging for fuel.”

Gauthier said the turbines in Vermont’s showcase Searsburg wind farm are like “kinetic sculptures.” Ekedahl said the Searsburg turbines look like “benign sentinels” when they’re inactive.

But some Vermonters are decrying the potential loss of their familiar vistas, as are residents of states from Massachusetts to Michigan. Such aesthetic opposition to wind farms is as common in the U.K. as in the United States, Beesley says, noting local opposition to the erection of 300-foot-plus wind turbines in an old airfield near his home.

Like the other artists, Beesley rejects the view that renewable energy must have zero impact. “I don’t buy this argument the countryside has to be preserved,” he said. “The landscape is constantly changing.”