Bruce Barcott.

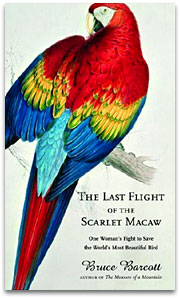

In his new non-fiction book Last Flight of the Scarlet Macaw, environmental journalist Bruce Barcott follows Sharon Matola — a former Air Force survival specialist and circus-tiger trainer turned zookeeper — as she fights the construction of a hydropower dam in her adopted country of Belize, and attempts to save the nesting site of the country’s last scarlet macaws.

During her years of battle, Matola — known throughout Belize and beyond as the Zoo Lady — wrestled with corrupt politicians, the habitual Belizean suspicion of outsiders, and her own impulsive nature. Though her campaign to stop the Chalillo dam ultimately failed, Matola remains a stubborn defender of Belizean wildlife. She’s now working with the Peregrine Fund to reintroduce the harpy eagle, a gigantic bird Barcott describes as a “bear cub with wings,” to the country’s forests.

Barcott first met Matola in 2002, while on assignment for Outside magazine, and tracked her and her crusade for the next several years. Along the way, he discovered that reporting in the tropics requires discretion, persistence, and snakeproof boots. Grist recently caught up with Barcott to talk about his adventures, and about the surprising victory that emerged from Matola’s messy international scuffle.

Sharon Matola.

Photo: Earth Expeditions

So what were your first impressions of the Zoo Lady?

My first impressions were immediate, vivid, and strong. That’s how she is — she’s this strong-willed, outgoing, and very charming woman who started and runs her own zoo in the middle of the jungle, in a very tough atmosphere. Belize today really reminds me of Alaska in the old days: if you go down there, you have to make your own way, essentially build your own house, and survive by your wits. That’s what Sharon is doing.

Tell us something about what Matola and her handful of allies were up against.

The government made a tiny announcement in the newspaper that it was going to let an energy company build this dam. Sharon was the only one who knew what was going on — she was the only one who’d actually been back in the area that was going to be flooded, because she had been doing some fieldwork on the macaws nesting back there. She started looking into the dam quietly and privately — she met with energy company officials, a couple of government officials, that sort of thing — and they brushed her off, saying, “You don’t know what you’re talking about.” She started fighting the dam by herself, and little by little she gained allies.

She also gained some very powerful enemies. The government spokesman said all sorts of outlandish things about her — that she was an enemy of the people, that she was ruining the economy of Belize. Threats were made on her life and on the zoo — at one point, the government, in an effort to get her to shut up, decided it was going to move the national dump from an area outside Belize City to a spot right next to the zoo.

You followed this story through government and corporate offices in four countries — in some ways you must have been as absorbed in this battle as the players themselves.

I was. For me it was a microcosm of the environmental battles that are playing out around the entire planet. We were talking about a six-megawatt dam — that’s a tiny dam, not the Three Gorges. But it was part of the classic search for energy in a world of limits. In this case, the limits were the number of birds that are still alive in this tiny little country in Central America.

It was also a case of globalism coming up against environmentalism — this energy company based in Canada that was putting in this fairly destructive dam down in Central America didn’t really know all that much about Belize or what they were doing down there. The shareholders, who were essentially responsible for the project, just didn’t care — it was too far away.

Were you surprised by the final outcome?

Sadly, no. I mean, you know, if you’ve been reporting in these areas for any time at all you can’t be surprised. At one point, Sharon says, “The odds are against us,” and one of the environmental lawyers looks at her and says, “Sharon, the odds are always against us.” Sometimes we get to hear about the victories that people like Sharon post — they stop a destructive project now and then — but most of the time these projects go on. It’s money talking.

By the time someone like Sharon spots a destructive project like this and starts to battle to stop it, it’s really too late. If you’ve got an area like the Macal River — the river that was flooded by the dam — that really should be protected, you have to protect it now, before oil is found, before it’s a site for a dam. Once that money starts rolling in, it just speaks volumes and it’s hard to overcome.

By the time someone like Sharon spots a destructive project like this and starts to battle to stop it, it’s really too late. If you’ve got an area like the Macal River — the river that was flooded by the dam — that really should be protected, you have to protect it now, before oil is found, before it’s a site for a dam. Once that money starts rolling in, it just speaks volumes and it’s hard to overcome.

The Natural Resources Defense Council played a complicated role here, as an outside environmental group trying to stop the dam. Were there any lessons learned for U.S. groups working on international conservation projects?

Sharon could not have taken this battle as far as she did without the NRDC, but at the same time their role was very complicated. The people who came in from NRDC, Jacob Scherr and Ari Hershowitz, are very smart; they run international campaigns all over the world, and they know they can’t just come in by themselves and start a fight. They try to come in and support local people. The problem in Belize is that it’s such a small country — at the time there were only 275,000 people — that you have only a few people fighting these battles, and when you get an organization as large as the NRDC coming in, their footprint tends to be much bigger than they want it to be.

So the government and the energy company were able to use the NRDC name and image against itself. They framed the battle as outsider environmentalists coming in and telling Belize what they could and couldn’t do — which is ironic, because a similar thing could have been said about the energy company, that it was a foreign corporation coming in and essentially buying a Belizean river. That was a difficult thing for Sharon and the NRDC to overcome.

Jacob talks about the lessons that he and the NRDC learned from the Chalillo battle, and one of the main ones is that they really have had to ramp up their alternatives program. They’re fighting similar battles in Chile — there are a couple of huge hydro projects going in in Patagonia — and in Costa Rica, and one of the things they’re doing now is really working to not just be critics of these energy projects, but partners with the governments and energy companies in developing alternatives for energy conservation and production, so that they don’t say, “Well, you can’t do this.” They’re trying to say, “Hey look, this alternative is much cheaper and more efficient, and it doesn’t damage the environment.”

This battle took a huge personal toll on some of the players.

It took a heavy emotional and physical toll on Sharon and on the zoo. She’s a person who’s very attached to wildlife — she runs a zoo, its animals are her life, and she was very attached to those scarlet macaws. It was personally painful for her to have come face to face every day with the fact that those birds and their nests were likely to be drowned.

Fighting this battle also cost her a lot of friendships. In a country that small, there are basically 1,000 people who run things — they’re all related, and everyone knows each other. For most, politics are just politics — at the end of the day, you all go out and have a drink. But for Sharon it was really personal, and that cost her friendships — she’s still working on building those relationships back up.

Why do you think she was willing to pay such a price?

Over her lifetime, especially over the 20 years that she’d lived in Belize, she’d seen animals slowly go away. In Belize, there used to be reports of scarlet macaw overflights and feeding flocks in many different parts of the country, but slowly those reports stopped being heard. A patch of forest here or there would be cut down, and a feeding site would be lost. She’d seen this happen with jaguars, with tapirs, with other animals around Central America. With the macaws, I think it was finally time for her to put her foot down and say, “Enough.” If you don’t stand up and say something at that point, when for her the issue was so clear, then you’re not going to do it for any animal, any piece of habitat. So it was a culmination of a lifetime of watching these animals slowly disappear.

This is, at least on the surface, a sad story. Did you find reasons for hope?

The reason for hope in the book is Sharon herself. Species are dying out because we’re losing habitat acre by acre — not slowly but quickly — but there are also people like Sharon who are fighting every day to save habitat, and they’re doing it. Before she came along, Belizeans really didn’t know what the wildlife of Belize was like — they had all sorts of myths about how a tapir or a jaguar would make your dog go crazy or your children go blind. Over the course of 20 years, she essentially turned the scary wildlife of Belize — that people would either run from or shoot to kill — into the national treasure of Belize. She runs every schoolchild through the zoo every year, and she’s got an entire generation of Belizeans who grew up loving wildlife. That’s the result of one woman doing this work every day.