One of the six key elements of the international agreement is: strong leadership from developed countries with firm and aggressive emissions reductions targets in the near-term (e.g., 2020 and 2030) and strong signals that they will significantly reduce emissions in the medium-term (e.g., 2050).

As I discussed in Part 1, the expectations for Copenhagen are that all developed countries will outline the further emissions reductions targets that they’ll undertake. Then next year these commitments will be firmed up (e.g., with more political backing to ensure that they are achieved or made more aggressive) and translated into legally binding commitments.

Copenhagen has been an important driver in encouraging developed countries to bring forward further commitments to curb their global warming pollution. Almost all developed countries have put forward more aggressive targets for 2020 that outline much deeper emissions reduction commitments.

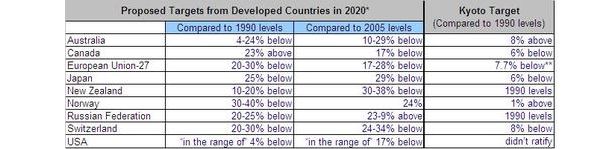

With a few exceptions, notably Russia and Canada, these are deeper cuts than those countries are bound to meet under the current targets of the Kyoto Protocol. The following table summarizes those targets or ranges.

While the U.S. is working through its domestic legislative process in order to have a firm commitment that the U.S. can “stand behind” and that the world knows it will achieve, President Obama last week outlined a “provisional target”. It is important to note that provisions in the House passed bill would increase the U.S. contribution to 28-33 percent below 2005 levels in 2020 (or 17-22 percent below 1990 levels). Other countries have proposed a target range, based upon certain conditions being met — usually if there is a strong international agreement with deep emissions cuts from all developed countries and significant actions from major emerging economies. In some cases we expect that developed countries with a range may firm up their specific target this year, while other countries may firm up their commitment next year as a part of the effort to finalize the legally binding agreement.

In addition to the important discussions on the level of the target, there are three important elements of the international agreement related to these developed country targets which have an important impact on the environmental outcome of these emissions cuts — these are considered the key architectural elements.

- Are countries held to a set of standardized systems to measure, report, and verify actual emissions and achievement of their commitments? We need to have a way to compare “apples to apples” and make sure that we are accurately assessing actual overall emissions. And we need to see how information on actual emissions compares to the targets that countries committed to.

- How do you account for changes in emissions and increased carbon sequestration from land-use activities? This issue has the unfortunate name of “Land-Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry” (LULUCF) and is often one of the more technical and complicated aspects of the negotiations. But how these rules are defined can have a very important impact on the environmental outcome of the agreement. This issue has a long history in the negotiations of almost “sinking” the whole deal. I don’t think we are headed for this issue sinking the new agreement, but without a strong set of rules for LULUCF emissions accounting we may not see as strong of an environmental outcome as the targets may appear on the surface.

- Do countries also bring forward targets for additional years beyond 2020 and how firm will those ultimately be? The effort in 2020 is extremely important, but it is also important to consider whether countries are also making deep cuts in 2025, 2030, 2040, 2050 and so on. As a part of the G8 agreement all developed countries committed to an 80 percent cut in emissions by 2050 (see my summary here) and when articulating the “provisional” target the U.S. outlined some of the targets past 2020.

It isn’t clear exactly how many of these details will be agreed this December in Copenhagen or whether they will be agreed next year. But they need to be resolved in a very credible way as a part of the final legal agreement as they are critical to the environmental outcome that this new agreement will achieve. After all, solving global warming doesn’t depend on what you say your effort will achieve. Rather it depends on whether you are “really” taking that amount of global warming pollution out of the air. Without these key architectural elements it would be like having a company that looks on paper as if it is making a profit, but in reality it is bankrupt.

“Locking in” what we have and deepening. If we look back to where we were just two years ago in Bali, Indonesia, in some sense it is a very positive step that we have all these developed countries with deeper cuts on the table. It isn’t enough and clearly we’ll need more from these countries and the clear steps to actually achieve them. But let’s “lock in” what we have to date and find ways to make them even deeper.

———-

* Some countries have outlined that a part of these targets will be met through accounting for changes in emissions and sequestration from land-use. As best as possible I attempted to define the targets according to whether the country assumed that LULUCF would be included. Different accounting rules for LULUCF would result in different effective targets (see: Climate Action Tracker).

** E.U. 27 target is estimated by Climate Action Tracker; E.U.-15 had a joint target and other Member States that later joined the E.U. had their own individual targets.

Spread the news on what the føck is going on in Copenhagen with friends via email, Facebook, Twitter, or smoke signals.