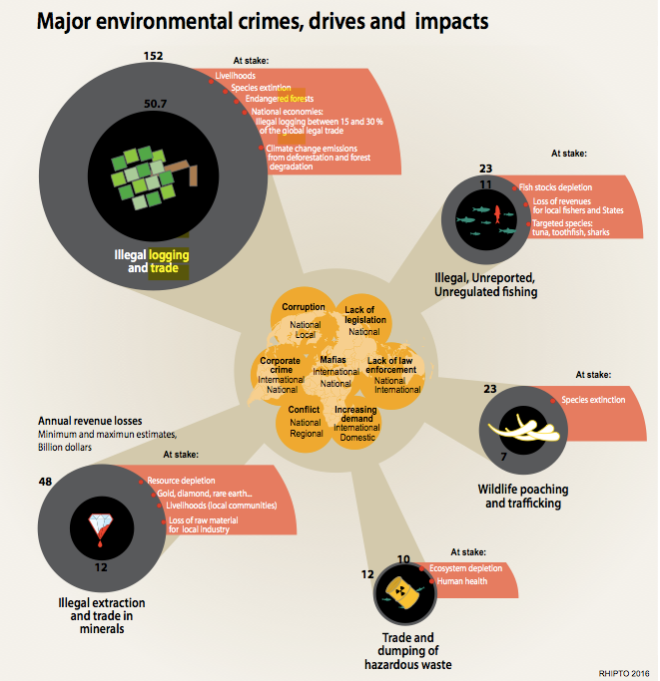

Environmental crime, according to a new report released by United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and INTERPOL, is booming — and we’re not talking about neglecting to separate your glass and plastics. These offenses — which include things like cutting down trees, overfishing, dumping toxic waste, and killing endangered species and selling their body parts — are actually much grislier than they may sound. Think Scarface, but with pangolins.

INTERPOL estimates that the dollar value of the criminal trade in wildlife, illegally logged lumber, fake carbon credits, and a whole smorgasbord of illicit environmental behaviors is an unpleasant financial success story, with revenues growing at a rate of about 6 percent a year. That’s twice as fast as the global economy.

What does the actual landscape of environmental crime look like right now? In a word: bleak. If you have a passing knowledge of the state of wildlife today, for example, you already know that it’s not a great time to be a rhino.

There aren’t many solutions explicitly provided by the report itself — they boil down to “give INTERPOL more money to train international wildlife rangers” and “countries, try to work together.” But buried within the depressing statistics, there’s evidence of a broader set of ways to tackle so much snow leopard-smuggling. Some of them are already in progress (like the international effort to slow down deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon) — and others are very much still waiting to happen.

Make crimes against the environment higher-stakes than selling drugs.

Right now, environmental crime is a cozy sideline for risk-averse lawbreakers. The UNEP report says that international drug cartels have expanded to dealing in natural resources — which makes sense. If you’re good at smuggling kilos, why not look around for new — and less perilous — things to diversify your enterprise? As a result, we’ve seen an expanding market for endangered species, ozone depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), minerals, gold, charcoal, and timber.

Treat arms dealing as an ecological issue as well as a political one.

Much of the trade in wildlife and illegally logged and mined resources is controlled by military groups or former soldiers armed with weapons left over from old wars — like the Congo War, for example — or purchased under dubious circumstances. The migration of guns around the world is a major public health risk, and should be treated as such.

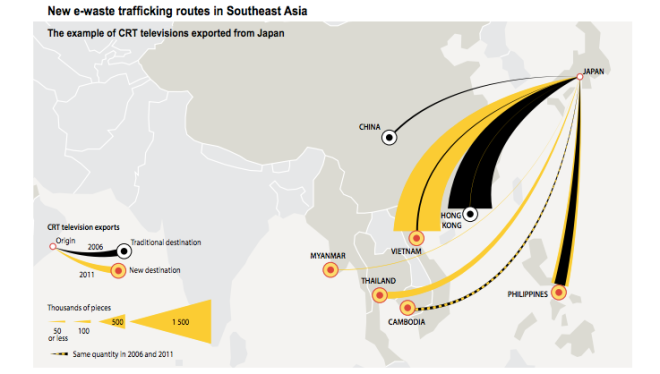

We need an international effort to stop e-waste from being dumped on countries with the weakest enforcement of environmental standards.

Good news: We can start on this right at home because the United States never ratified the Basel Convention, which regulates the movement of toxic waste around the planet. The United States could also develop a federal standard for e-waste recycling (22 states have no regulations for this at all). Because our own rules are so lax, even in situations where e-waste is supposed to be recycled ethically and responsibly in the United States, it mysteriously winds up polluting the rural countryside of a foreign country anyway.

We need to be able to track the most valuable environmental resources (trees and fish) on a global scale and eliminate the black market for them.

Grist’s Amelia Urry once wrote that “fish are great at fighting climate change. Too bad we’re eating them all.” An estimated 18 percent of the world’s fishing catch is illegal — meaning that already overfished stock is being further depleted. There’s no better time to develop and implement a way to track fishing vessel registration worldwide, while climate accords are still fresh and the countries that signed on are still in a collaborative mindset.

A few hopeful signs: Since 2012, the U.S. Navy, the Coast Guard, and Pacific Island nations have worked together via the Oceania Maritime Security Initiative to police overfishing in the Pacific Ocean. And the U.S. State Department has already expressed significant interest in developing a way to track fishing vessel registration worldwide.

One thing that the UNEP report does not approach is bad environmental behavior that’s perfectly legal — or, for that matter, how to deal with it. Like, you know, pumping so much CO2 into the atmosphere that you disrupt the carbon cycle and, oh boy, how’s it going to go for the United States if the international community ever decides to do something about that besides politely asking us to sign treaties that are don’t really force us to do that much anyway? Best not to think about it, and focus on that technology for tracking illegitimate fishing vessels.