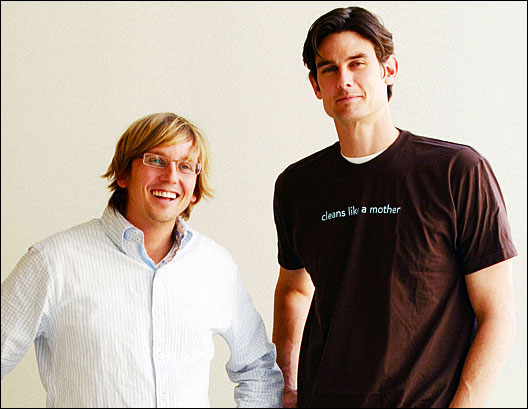

After spending a few minutes with Adam Lowry and Eric Ryan, I began to wonder if they weren’t part of a modern-day adaptation of The Odd Couple. The 30-something founders of the Method line of home-care products, friends since high school, are about as different as two business partners could be.

Lowry (Method’s “chief greens keeper”) is tall and lanky, with dark brown hair. The day we met, he was wearing a classic slacks-and-button-down number and a serious look on his face. He’s a chemical engineer with an environmental degree and has worked as a climatologist at the Carnegie Institution. And his favorite Method scent? “Classic lavender.”

Ryan (“chief brand architect”) is about a head shorter. His tousled blond hair and wide smile give him a laid-back surfer air; his tailored jeans and tee, an edgy hipness. He’s a marketing guru who’s worked for Gap, Saturn, and other brands. His favorite Method scent is “whatever’s new.”

Put them together, and you’ve got a philosophy that blends substance and style — and a product line that boasts more than $75 million in annual sales. The company has also received accolades for packaging design — a distinction that quite literally sets them apart from competitors on the shelves. Partnering with designer Karim Rashid, whose clients range from Dirt Devil to Prada, they’ve created, among other things, an hourglass-shaped dish-soap bottle that squirts from the bottom via a non-leaking spout.

They’ve also been recognized for their commitment to sustainability — receiving nods in 2006 both as PETA person(s) of the year and in Time‘s “Who’s Who Eco-Guide” — for their pledge to create products that are nontoxic, cruelty-free, and made of “ingredients that come from plants, not chemical plants.”

As old friends tend to do, Lowry and Ryan continually played off each other during our conversation. They made jokes and finished each other’s sentences as we talked about their upcoming book Squeaky Green, the “green chefs” who test and re-test every product, and a philosophy that focuses on progress rather than perfection.

A big part of your philosophy is the intersection of sustainability and design — can concern for health and the environment be both hippie and hip?

Lowry: What the style element does is it creates mass market relevance for a green product. And I’m not just talking about Method right now, although that is very much our strategy. We’re not the first company to think cleaners should be green, but we are doing them in a way that makes them accessible both from a price-point standpoint and from a design/aesthetic standpoint to everyone else who isn’t this sort of tree-hugging granola — forgive the expression …

Why would you do all this green stuff and then just hang out with other greenies? That’s one of the biggest reasons why the traditional environmental movement has not succeeded. It’s not democratic.

One of the big goals with Method, and why design and sustainability are inextricably linked in our brand, is that if you don’t have the design element, you’re only going to appeal to people who are already green, so you’re not actually going to create any real environmental change … To us, “sustainability” and “green” are just aspects of the quality of our product — they are not a marketing positioning … I mean everything should be that way. Just build it into the quality of the product and let the experience of the product be the real hero.

Ryan: Before Method came in, the whole idea of an eco-cleaner’s design was that it was supposed to look like you were suffering. Like the packaging was a little drab, a little ennui — that was kind of part of choosing to buy one of these products. You were making that badge of “I’m gonna suffer, I’m making this compromise for the environment.”

Lowry: It’s a very Catholic sentiment. You’re paying your penance for the Earth that’s dying, and you need to save it. And there are very few people who are willing to do that. I was one of those consumers when I was working for Carnegie. I was continually frustrated that you buy these green products, and they cost more, they don’t work, they’re not fun to use. It’s like guilt and absolution, instead of living a positive, healthy lifestyle.

Ryan: To Adam’s point, that’s how you create mass-market relevance: you bring the style and the substance. It’s challenging, though, because a lot of things that are very stylish really are not very good for the environment. We could make our products look way better than they do today, but unfortunately it would require making trade-offs with materials that, while they look beautiful on the outside, aren’t necessarily that beautiful on the inside.

Speaking of not being beautiful on the inside, your new book is basically revealing “dirty little secrets” of the cleaning-product industry.

Lowry: The purpose of the book is to be really provocative, and to just challenge some of the assumptions of why is cleaning such a dirty job and what is really dirtier — the things that we’re cleaning up or the things that we’re cleaning with? Method’s one part of that, but there’s lots of other parts that are important — whether it’s countertops, the Energy Star appliances, the flooring, or just simple things like kicking your shoes off when you walk in.

What “dirty little secrets” are people most surprised to hear?

Ryan: The light bulb goes off the most [with] things that seem so obvious but you never stop to think about it. [Like] the idea that you clean your tub with toxic cleaner, but then you soak in it afterward.

Are there any products you wish you could create? Problems you haven’t found good solutions for?

Lowry: One of the ones we’ve been working on for a long, long time is toilet-bowl cleaner.

Ryan: I thought it was toilet paper. What have I been testing at home, then? [Laughs.]

Lil’ Bowl Blu and Le Scrub: A greener blue toilet.

Lowry: With the toilet-bowl cleaner, for a long time, we have struggled to make it work as well as the toxic, phosphoric-[acid], sulfuric-acid toilet-bowl cleaners. But we have now found a technology that will allow us to do that, so we’re very close on that product. [Ed. note: their Lil’ Bowl Blu nontoxic toilet cleaner launches this month.]

Ryan: We like to do what we call “two revolutions a year” — which are big, revolutionary products. O-mop, [a microfiber-cloth floor mop], is one from [last] year; the other one is the “bloq line” of personal-care products. For 2008, we’ve got a couple of “revolutions” lined up that are really cool — we can’t let the cat out of the bag right now, but they will be in two new categories where it’s ripe for revolution. Beyond that, it’s classified, and I’d have to kill you …

Tell me about the decision to sell your products in mainstream stores.

Lowry: If you want to use your business to create change, you need to create change where the change is needed — and that is with people who are unaware of even the fact that we have these issues, or even worse, they’re people who have decided that the trade-off that they’ve been told they must make in order to live a green or a healthy lifestyle isn’t worth it. We’re trying to show people that if they had a misperception that green had to cost a lot of money or green had to be difficult or green had to be penance-oriented or–

Ryan: Can’t come in bright colors —

Lowry: Right, then that’s wrong. And it’s not only wrong with our stuff, which helps maintain your home, but also that assumption is wrong with the way that you decorate, the foods that we eat, the experiences that we have — so top-to-bottom in the home. You can do it, and it’s actually really easy. Because if it’s not easy, people aren’t going to do it.

Ryan: Plus, these retailers really got behind us and helped us push that change. Target was a great partner in that and Costco’s been a fantastic partner … We didn’t want to go try to steal share from the other natural cleaners; we wanted to go where there were no natural cleaners at that time.

Lowry: One of the things that I think we’re really proud of … is [how] the success that we’ve had in bringing green- and health-focused products to the mass market [has] actually changed the market much bigger than our own footprint.

In 2004, we launched the first triple-concentrated laundry detergent into the mass market that was successful, and we did that on a national basis. Wal-Mart saw that; we talked to them about the benefits of triple-concentrated laundry detergents, and they started pressuring their manufacturers into it.

… [B]asically, the entire laundry category has changed because Method paved the way and showed that there was an innovation that could be done here that was better for the consumer because you’re not carrying this giant jug of stuff around, it was better for the environment because you’re not wasting as much, and it was better for the washing machine and for your wallet — and it was really just a simple design solution.

Speaking of Wal-Mart, have you ever been accused of greenwashing?

Lowry: I’m sure that there’ll be more criticism as we get bigger … I can even anticipate what some of those things might potentially be. But our philosophy … is about progress, not perfection; it’s about moving that ball down the field one innovation at a time.