How long could you survive without your car? For the many Americans who think nothing of driving 10 blocks to buy a gallon of milk, the answer is obvious. But before any of you dedicated pedestrians and die-hard cyclists start feeling smug, try this question: How long could you survive without talking?

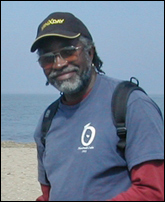

Chances are, nowhere near as long as John Francis did. After a massive oil spill polluted San Francisco Bay in 1971, Francis gave up all motorized transportation. For 22 years, he walked everywhere he went — including treks across the entire United States and much of South America — hoping to inspire others to drop out of the petroleum economy.

Soon after he stopped riding in cars, Francis, the son of working-class, African-American parents in Philadelphia, also stopped speaking. For 17 years, he communicated only through improvised sign language, notes, and his ever-present banjo. The environmental pilgrim says he took his vow of silence as a gift to his community “because, man, I just argued all the time.” But it may have been Francis who benefited most of all. For the first time, he found he was able to truly listen to other people and the larger world around him, transforming his approach to both personal communication and environmental activism.

Francis started speaking again on Earth Day 1990. The very next day, he was struck by a car. He refused to ride in the ambulance, insisting on walking to the hospital instead. With a Ph.D. in land resources (earned during his silence), he was later recruited by the U.S. Coast Guard to write oil-spill regulations and by the United Nations Environment Program to serve as a goodwill ambassador.

Francis, the author of Planetwalker: How to Change Your World One Step at a Time, is now preparing for a second environmental walk across America. He spoke with writer Mark Hertsgaard about how social change happens, the decency he encountered among red-state Americans, and the importance of bridging the chasm between white and black environmentalists.

Why did you stop riding in motorized vehicles?

This was the first time I had ever been exposed to an environmental insult of such magnitude — 400,000 gallons of oil spilling into San Francisco Bay. And I couldn’t get away from it. You could close your eyes, you could turn around, but you just couldn’t get away from the impact of it. The smell was overpowering. I decided I wanted to do something, but I didn’t know exactly what. I mentioned to a friend that I wanted to stop riding in cars, and she laughed at me and I laughed at myself and that was the end of it.

It wasn’t until a neighbor died the next year that I … He had a good job as a deputy sheriff, he had a wonderful wife, lovely kids, he just had everything. And from one day to the next, he was gone. So I realized there weren’t any promises. If I was going to do anything, I had better do it now. Because now is the only time we have to do what we need to do.

But one could have that feeling and say, “OK, I’m going to join the Sierra Club. I’m going to write my senator. I’m going to carry a picket sign outside the oil companies.” Not many people would say, “I’m going to stop riding in motorized vehicles.” Did it strike you as extreme?

It did. But it struck me as the most appropriate thing I could do. I could join the Sierra Club, I could carry picket signs, and people have been doing those things. But in my life, what could I do? And that was: not ride in cars. And I thought everyone would follow. (Laughter.)

You write about this in your book, that you had an inflated sense of yourself at that time. Not long after, you took a very radical step to confront that.

As I walked along the road, people would stop and talk about what I was doing and I would argue with them. And I realized that, you know, maybe I didn’t want to do that. So, on my [27th] birthday, I decided I was going to give my community some silence because, man, I just argued all the time. I decided for one day, let’s not speak and see what happens.

I’m going to read a passage from your book about your decision to stop speaking: “Most of my adult life I have not been listening fully. I only listened long enough to determine whether the speaker’s ideas matched my own. If they didn’t, I would stop listening, and my mind would race ahead to compose an argument against what I believed the speaker’s idea or position to be.”

That was one of the tearful lessons for me. Because when I realized that I hadn’t been listening, it was as if I had locked away half of my life. I just hadn’t been living half of my life. Silence is not just not talking. It’s a void. It’s a place where all things come from. All voices, all creation comes out of this silence. So when you’re standing on the edge of silence, you hear things you’ve never heard before, and you hear things in ways you’ve never heard them before. And what I would disagree with one time, I might now agree with in another way, with another understanding.

Some people reading this interview might say, “That sounds awfully passive if all you do is listen when ExxonMobil says there’s no global warming or when the Bush administration says we can have healthy forests by cutting them down.” Is there a danger that the philosophy you’re expounding is too passive in the face of environmental destruction?

There’s always a danger for anything to become not appropriate. But at the same time that I was listening, I was also walking. I was making a statement for other people to see, and perhaps to inspire them. The most you can do is be who you are and do what you do. You’re the only person you really have a moral obligation to change. What everyone else does, you don’t have any control over that.

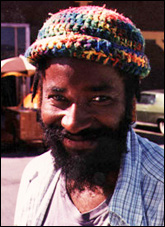

You began walking in the 1970s here in Northern California. Your first long walk was to Sacramento, the state capitol, to testify before a Senate committee. Then you took a longer walk up the coast to the Pacific Northwest. Eventually you walked across the entire country. You were an African-American man, with a banjo and a backpack, and you were silent. Did people treat you as an oddity?

Well, you know, I did look different.

Even for the 1970s!

Even for the 1970s. (Laughter.) I realized early on that I was gonna have to not worry about how I looked. It was really good for me to let my image go, the image I had before — that I had to wear the right clothes, drive the right car, use the right cologne. All those things went out the door, and I allowed myself to be a clown.

Nowadays, many of us think about America as split between red states and blue states. Was that your experience while walking across the country?

Well, I walked across a lot of red states, and the people in those states were just as generous, or even more so, as the people in blue states. In fact, when I walked across the country, there were no red states, there were no blue states; it was just America. People you might think would not bring me into their home brought me into their home and put me down at the table with their family, with their children, and invited me to stay.

In your book you argue that the environmental crisis is really a crisis of the human spirit. Does that mean we have to wait for humans to become better people before we can solve the environmental problem?

I’m not sure I would say that humans are going to become better people, but I think humans are going to become who we are. Frankly, I look at my life and I go, “God, I have great hope for everybody!” Because I look at where I came from, and I could never have seen me walking across the country, silently going to school, and 20 years later I’m in Washington, D.C., writing federal oil-pollution regulations. Looking at my journey, which is part of all of our journeys, I have great hope.

As an environmentalist who is black, do you think the chasm between white environmentalists and non-whites will ever be bridged?

It has to be. How we relate to one another is essential to environmentalism. If you’re not talking about human rights, economic equity, mutual respect, you’re not really dealing with the environment. Trees are wonderful. Birds and flowers are wonderful. They’re all part of the environment. But we’re part of the environment too and how we treat each other is fundamental.

The day after you began to speak again, you were hit by a car on the streets of Washington, D.C. I can imagine some people saying, “The universe was sending a message there.”

I was thinking, “The universe is sending a message.” I’m lying there, and the ambulance comes and they’re strapping me down and I said, “Where are we going?” And the ambulance person says, “We’re taking you to the hospital, you’ve been hit by a car.” And I said, “You know, I think I can walk.” They stop and look at me and say, “Walk? You can’t walk. You’ve been in an accident.” And I said, “Well, I don’t ride in automobiles. I haven’t ridden in an automobile for 17 years. In fact, I didn’t speak for 17 years. I just started speaking yesterday.” And that’s when I see ’em start thinking, “We’re taking him to St. Elizabeth’s [psychiatric hospital] for observation.”

Finally one of the women said, “Why are you afraid of riding in cars? Is it a religious thing?” And I said, “No, it’s not religious.” “Is it a spiritual practice or something?” I said, “No.” She says, “Well, it’s principles, huh?” And I grab onto that: “Principles! Yes, it’s principles!” And she tells me, “Honey, if you can suspend your principles for five minutes, we can drive your butt to the hospital.” And I think about it and all I come up with is, “I don’t think principles work that way. You can’t just suspend them for five minutes.” Eventually, they let me walk.

In 1994, after 22 years, you decided to ride in vehicles again. Why?

Walking had become a prison for me. While it was appropriate to stop walking when I did, over the years it had calcified, because I never revisited my decision not to ride in cars. [One day,] as I was walking, I thought about the fact that I had worked at the Coast Guard, I had worked on the Exxon oil spill. And if they had said to me, “John, we could hire you, but you have to ride in a car and fly a plane,” I would have said, “I’m sorry, I guess I can’t work for you then.” And that would have been the wrong answer. So I decided I needed to break out of the prison.

You were on the Venezuela/Brazil border when you stopped walking. How did it feel?

There were two women from the Netherlands who were walking with me. And when I got into the bus [on the border], they looked at me like, “Oh God, something’s going to happen to him. He’s gonna start crying or whatever.” But I didn’t. I just got in and I realized that I was in a VW now and I could feel the industry of transportation. I could feel the cogs of transportation. You know, the asphalt road, the gears turning, the fire, the pistons banging, and the fuel exploding — I could feel all that. It was a very interesting moment for me.

No guilt?

No guilt at all. This was the decision I was going to make.

You’re about to start another long walk, and obviously you’re a little older now and you have a family. You’ve talked a little bit about how you hope walking will affect the world around you. How about the world inside you? How will this time be different?

I don’t know how I’m going to change. I don’t know how it will change me. That’s part of the mystery of walking, is that the destination is inside us and we really don’t know when we arrive until we arrive. One of the biggest epiphanies that I’ve had was that, you know, environmentalists like to look at the industrialists or at the developers and say, “They gotta change. If they would change, everything would be all right.” But really, we all have to do that. We all need to look at ourselves. We need to re-imagine ourselves.