This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

On an afternoon in late June, the San Luis Reservoir — a 9-mile lake about an hour southeast of San Jose, California — shimmered in 102-degree heat. A dusty, winding trail led down into flatlands newly created by the shrinking waterline. Seven deer, including a pair of fawns, grazed on tall grasses that, in wetter times, would have been at least partially underwater. On a distant ridge, wind turbines turned languidly.

That day, the reservoir, California’s sixth-largest and a source of water for millions of people, was just 40 percent full. Minerals deposited by the receding waters had turned the reservoir’s lower banks white, like the rings on a bathtub. Discarded clothing, empty bottles, and a lone shoe sat scattered across the newly exposed, parched ground. An interactive graphic in the visitor’s center reported that this year’s snowpack — which provides the water that travels from the Sacramento River Delta into the reservoir itself — was zero percent of the yearly average.

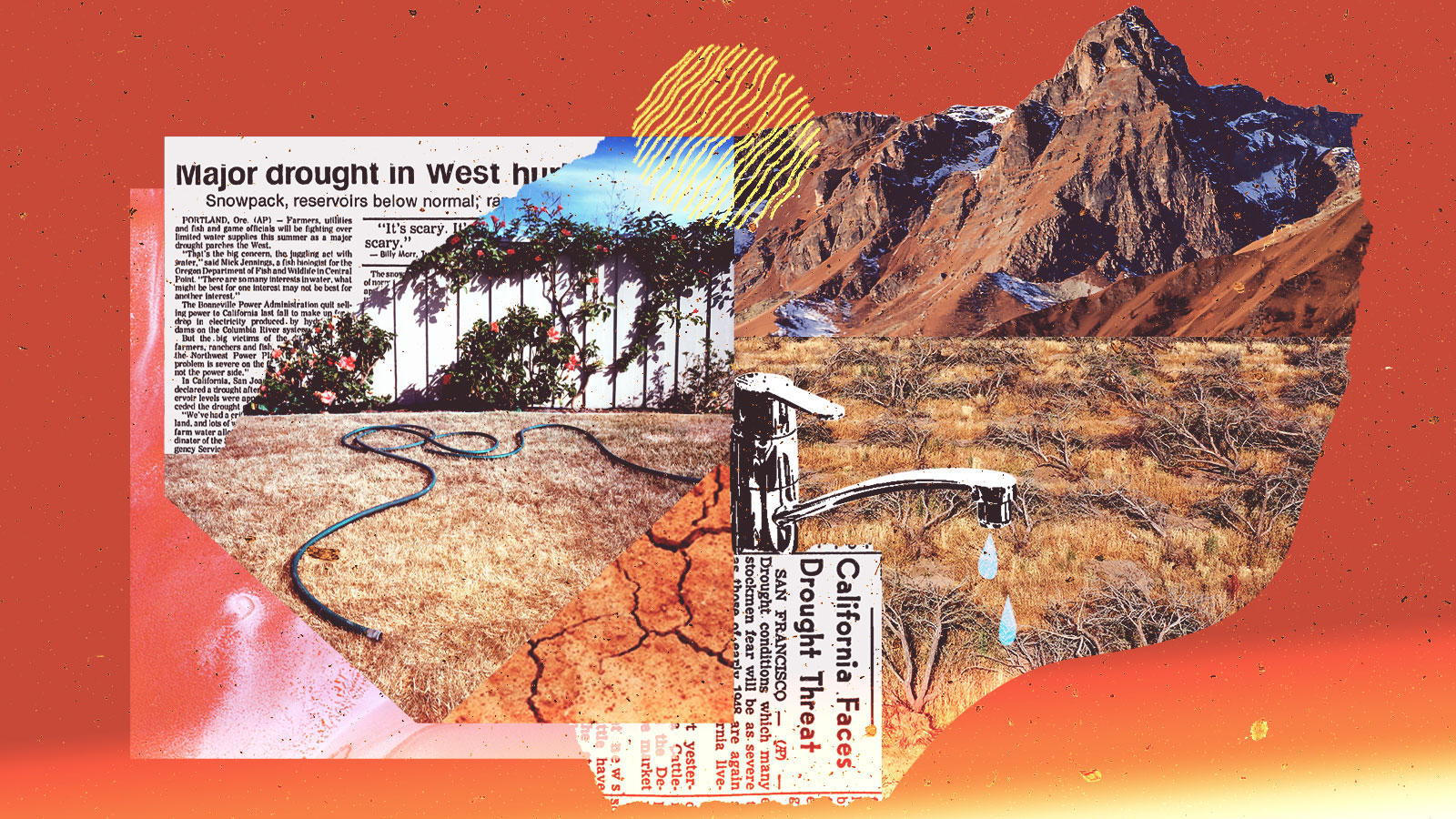

Depending on how you look at it, California — and most of the American West — has either entered its third catastrophic drought of the past 10 years, or has been in a constant, unyielding “megadrought” since 2000. Reservoirs are emptying; lawns are turning brown; swaths of farmland that have coaxed lettuce, almonds, and alfalfa out of the dry ground for decades are going fallow. The Colorado River, which originates in the snow-capped Rocky Mountains and provides water to some 40 million people in the Southwest, has slowed to a trickle. That waterway also feeds the largest reservoir in the United States, Lake Mead, 40 miles east of Las Vegas, which in recent months has seen water levels so low that bodies have emerged from its shrinking, normally crystalline waters. The Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency responsible for many supersized water projects, has asked states to cut their use of water from the Colorado River by 2 to 4 million acre-feet, an amount close to all the water that California receives from the Colorado in a single year.

Throughout the West, anxiety about drought is as palpable as the dryness of the air; talk of water fills newspapers and conversations alike. “Aridification kills civilizations. Is California next?” read one Los Angeles Times headline in June. In February, scientists confirmed that the current, decades-long “megadrought” is the worst in 1,200 years. They also confirmed that rising temperatures — driven by human consumption of fossil fuels — were partly to blame.

In one sense, the climate change link seems obvious. Since 1850, global temperatures have climbed 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit); in areas of the U.S. hit hardest by drought, the increase is even higher. Temperatures in California have risen about 3 degrees F since 1896; in Arizona, they have gone up by 2.5 degrees.

But the connection between climate change and drought is not as straightforward as it seems. Some areas are likely to get wetter while others get drier. Still others may accumulate the same total rainfall, but in inconsistent patterns: More rain might fall in fewer, more intense bursts, followed by longer dry spells. “It’s complicated,” said Benjamin Cook, a climate scientist at NASA and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

But scientists can say some things with certainty. As the world gets hotter, soils are getting drier; it takes more and more precipitation to water the same crops and fill the same reservoirs. Rising temperatures, therefore, are digging the American West and other arid regions into a deeper and deeper hole. The more the world warms, the more rain will be needed to compensate, and that will force people to rethink how — and where — they will live and eat when the water dries up.

One problem with linking drought and climate change is that there is little agreement on what drought actually is. “No two people — including no two scientists — really agree on even how to define drought,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles. A drought, in its most general sense, is simply a lack of water relative to some long-term average — but where that dearth of water appears can change how the drought is defined, studied, and managed. Climate scientists and meteorologists talk about “meteorological drought” (a lack of rainfall), farmers worry about “agricultural drought” (a lack of soil moisture), and water managers try to avoid “hydrological drought” (a lack of groundwater or water in reservoirs).

This complexity has resulted in conflicting messages about the role of human-caused global warming in the droughts that have ravaged the American West and the rest of the world. Thanks to the science of extreme event attribution, which connects weather extremes to global warming, it has become commonplace to cite climate change as a factor in devastating heat waves or torrential floods. But droughts are trickier. Drought depends on both the rain that falls and how quickly it is evaporated and used.

On the rainfall side of things, climate change’s influence in California, Nevada, Arizona, and other Western states remains murky. In recent years, rain and snowfall in California have become more variable; the dry years are drier, the wet years wetter. In 2017, Lake Oroville served as a sobering illustration of this whiplash when — in the span of less than four months — the reservoir north of Sacramento went from less than half full to nearly overflowing, causing the main spillway to collapse. Some 188,000 local residents were evacuated. Swain and his colleagues estimate a 25- to 100-percent increase in such “extreme dry-to-wet precipitation events” in California over the next century.

But even with this volatility, total precipitation in the West is expected to stay roughly the same. Swain said scientists expect the Pacific Northwest to get somewhat wetter; Arizona and New Mexico somewhat drier. The clearest link between drought and climate change right now, therefore, is not a lack of rainfall — it’s rising temperatures.

The atmosphere is like a sponge: It sucks up water from soils, plants, rivers, oceans, and lakes. Any time rain falls, some of it will evaporate, returning back into the sky before it can be piped into homes, fields, or aqueducts. Scientists have a measure for how “thirsty” the atmosphere is, or how much water the sky absorbs: evaporative demand. As temperatures go up, evaporative demand increases. The sky gets thirstier.

“A very basic rule is that if you’re going to have a warmer atmosphere then you need more precipitation to compensate,” said Park Williams, a hydroclimatologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “If you turn the heater up in your house and you don’t give your plants extra water, you see the same thing.”

Christine Albano, an ecohydrologist at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada, studies evaporative demand and how it might change under global warming. “A warmer atmosphere can hold more water,” she explained. And, she added, the changes are nonlinear — a small change in temperature could lead to a much larger change in how thirsty the sky is. In a paper published earlier this year, Albano and her co-authors found that evaporative demand has increased over the past 40 years, most dramatically in the U.S. Southwest around the Rio Grande River. In that region, evaporative demand increased by 8 to 15 percent — meaning that the area would require 8 to 15 percent more rainfall to maintain the same water levels.

And as temperatures warm, the situation will get even worse. “For every raindrop, we’re going to get less of that going into our streams and rivers,” Albano said.

That thirsty atmosphere has been behind most of the studies that have found a clear link between global warming and persistent droughts. The last catastrophic drought in California, which stretched from 2011 to 2017, drained reservoirs and forced farmers to pump groundwater from the state’s disappearing underground aquifers. Some scientists looked for a direct link between climate change and the lack of rainfall, but did not find convincing evidence. Those who looked at the effect of temperature on soil moisture and general aridity, however, found something more interesting: that human-caused climate change had turned what would have been a more moderate drought into a devastating one. In a paper published in 2015, Williams, Cook, and others found that skyrocketing temperatures, brought on by human-caused global warming, had made the drought 15 to 20 percent more intense.

Similar results have been found all over the globe. A few years ago, scientists analyzed the European drought of 2016 to 2017 — which helped spark deadly wildfires in Portugal — and found that it had been made worse by high evaporative demand. To the south, the Horn of Africa has been ravaged by a series of droughts over the last decade, causing successive crop failures and threatening millions with severe hunger and starvation. In 2015, scientists searching for ties to climate change found no connection to the region’s low rainfall. They did, however, find a link between rising greenhouse gas emissions and the high temperatures that have helped to desiccate the landscape of Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

Temperature has also been implicated in the study of the decades-long “megadrought” in the American West, a loosely defined term that has been used to indicate droughts that last two decades or more. Scientists have spent decades drilling holes in trees to collect tree ring records, a science known as dendrochronology, which can be used to estimate soil moisture levels going back for millennia. (Some records have even been collected from ancient wooden ladders in the cliff dwellings of Chaco Canyon.) According to those records, 19 of the last 23 years were drier than the average over the past millennium.

Williams, the UCLA scientist, says that this megadrought is being made even worse by climate change. “Forty percent of the severity of the drought conditions in this megadrought is attributable to human-caused climate trends” largely from rising temperatures, Williams said.

Sixty percent of the megadrought, Williams cautioned, could simply be seen as simply bad luck; even without humans burning fossil fuels, megadroughts have endured for decades in the past, starving the landscape and local species of water. But what was previously just bad luck is now getting a boost from climate change. “It’s only going to get warmer,” Williams said. “It’s going to take more and more good luck to bail us out of drought — and less and less bad luck to fall back in.”

Climate change is also undermining one of the American West’s most treasured tools for managing drought: snowpack. In the Sierra Nevadas of California and in the Colorado Rockies, snow falls during the winter and then acts as a natural reservoir, slowly releasing water as it thaws during the hot, dry summer season. But as temperatures rise, more precipitation is falling as rain instead of snow, and any remaining snow is melting more quickly and earlier in the season. By 2050, scientists estimate that the mountains of the Western U.S. will lose around 25 percent of their snowpack. In 60 years, they warn, there may be no snowpack at all.

And, as the planet heats up, megadroughts such as the one raging in California, Arizona, and New Mexico are expected to return again. And again. According to one study by Cook, the NASA scientist, and others, the risk of a 35-year-long drought hitting the American Southwest was less than 12 percent between 1950 and 2000. But if countries fail to take aggressive action to combat climate change, and the world continues to warm, the risk of such a drought will climb to more than 80 percent.

The American West is built on a strange, hodgepodge system of water that, for the last century, has somehow sustained millions of residents in the most arid parts of the country. Reservoirs, dams, and aqueducts carry water from where it is plentiful — the peaks of the Sierra Nevadas, the banks of the Colorado River — and deliver it to where it is scarce: fast-growing metropolises like Phoenix, Salt Lake City, and Los Angeles. In California, 75 percent of the state’s rain and snow falls north of Sacramento, but 80 percent of its water demand comes from the southern two-thirds of the state. This imbalance is corrected artificially: A long cement aqueduct carries water from the north of the state to the south, shuttling through the dry, crackling Central Valley. More comes from the Colorado River, which brings water from the east to Los Angeles and Southern California.

This system has faced numerous droughts before. In dry times, policymakers call for cutbacks and march down the list of water rights-holders and inform each how their supply will be curtailed. The last big drought in California, which reached its peak in 2014 and 2015, saw residents “drought-shaming” one another for maintaining lush lawns (Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti called such shaming a civic duty) and an enormous backlash against almond growers, after news broke that it takes a gallon of water to produce a single almond.

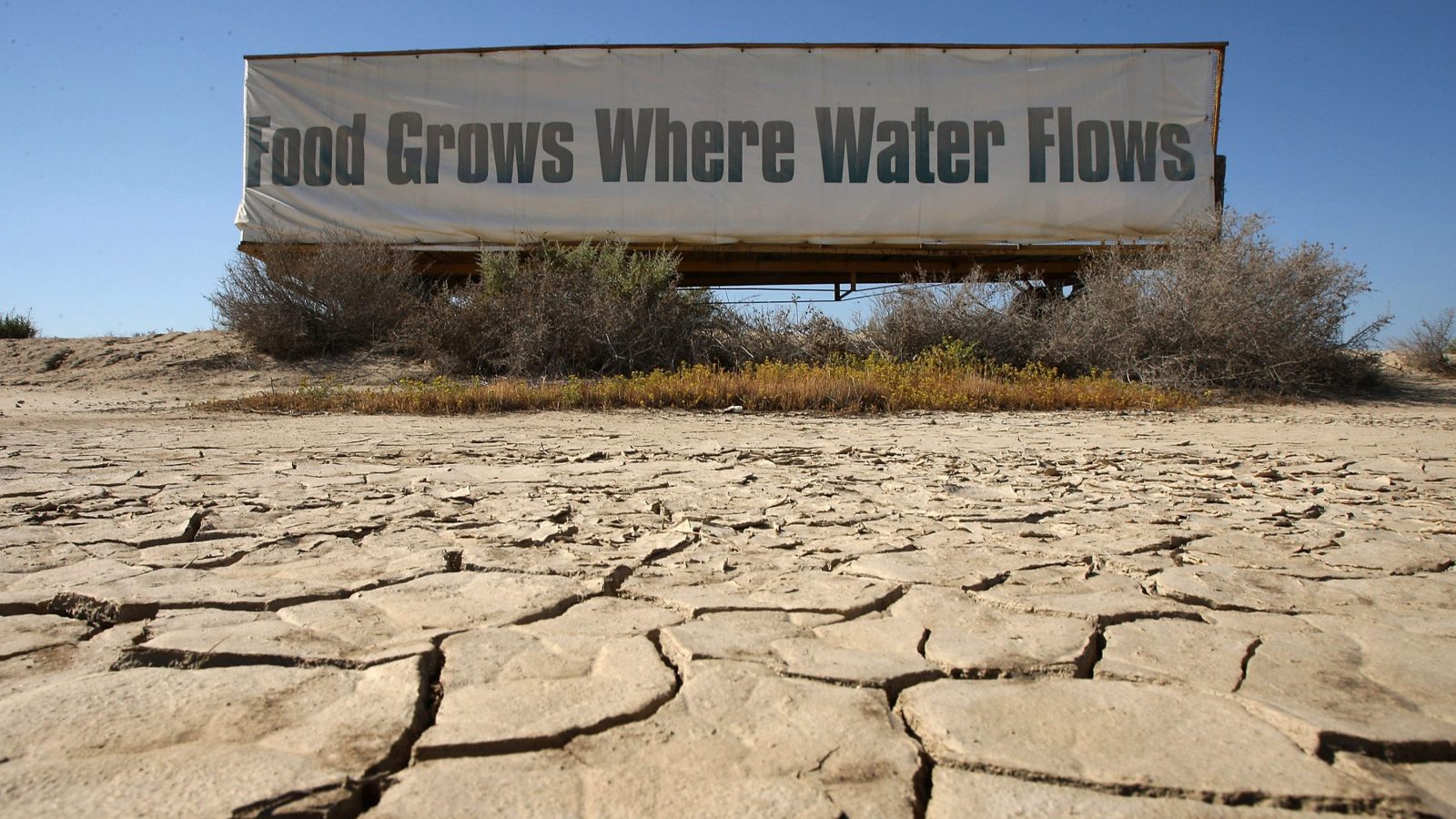

But the sheer longevity of the current dry period has even the most experienced water managers worried. That complex system of dams, aqueducts, and reservoirs that funnels water to Western states for lawns, golf courses, and farms is cracking under the strain. “We built these amazing places based on the promise of water,” said John Fleck, a professor of water policy and governance at the University of New Mexico. “And they’re good things — I don’t want to demonize what we did. But they were based on the promise of water that wouldn’t be there.”

To be sure, the current drought and even the overlapping, decades-long “megadrought” will eventually end. “I don’t expect it to be as dry as it has been the past few years forever,” Williams said. But the slow-moving disaster has demonstrated just how shaky the West’s foundation is. And it is a warning that the water system of the present may not hold for the future.

What will happen next? Nearly 40 million people live in California alone; another 12 million reside in New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada. And, in the wake of the pandemic, southwestern states are growing fast, as people look for more affordable housing, strong job markets, and warmer weather. But that warmer weather has a darker side. Not far from Phoenix, Arizona — one of the fastest-growing cities in the U.S. — one community is already running out of water. As the Colorado River and the snowcaps of the Sierra Nevadas continue to dry up, the water flowing to the West’s sprawling suburbs and millions of acres of farmland will slow to a crawl. When that happens, communities will need to adapt. Agricultural water use will have to decline — even if that means destroying livelihoods that have continued uninterrupted for decades. Lawns will dry up; lush golf courses will disappear. The very character of the West — and of many arid parts of the globe — will be transformed. “In some ways it’s really simple,” Fleck said, of the climate-changed drought future. “The West will be less green.”