What liberals and their allies in the environmentalist wacko movement fail to understand is: their message has gotten out. Their anti-capitalist, socialist, gloom-and-doom, fear-based, lunatic ravings have been amplified — and Americans understand exactly who they are, and what they’re about. As the “Mr. Big” of the vast right-wing conspiracy, I am proud, ladies and gentlemen, to play a major part in the exposé leading to their depression.

– Rush Limbaugh April 25, 2005

Currently, about 20 million people tune in to Rush Limbaugh every week. His lingo is now conservative lingua franca. Limbaugh figured out that if you repeat your best lines — e.g., “environmentalist wackos” — often enough, they become more than just funny catchphrases; they become a reconfiguration of reality and a call to arms. In his world (and it’s a world in which a lot of people live), you can’t be an environmentalist and escape wacko-ism.

In Limbaugh, a large group of Americans who felt their country was being taken away from them found an emotional outlet. If his facts didn’t always ring true, his anger did. Limbaugh proved that someone with a quick wit and a microphone could wield tremendous power, and his success spawned a legion of copycat shows across the country.

Filmmaker Patrice O’Neill at a

community screening of “The Fire

Next Time” in Montana’s Flathead

Valley.

Photo: Chris Peterson.

One of them is hosted by John Stokes of KGEZ in Montana’s Flathead Valley. Stokes is featured in the new PBS film The Fire Next Time, which premieres Tuesday, July 12. The documentary was made by Patrice O’Neill and The Working Group, a film company that also works with communities to overcome intolerance. The film follows several groups in Kalispell, Mont., over a two-year period in which their community goes up in flames — figuratively and literally — over conflicts about environmental preservation.

Everybody in Kalispell cares about trees. Trees feed the timber industry, help drain the land, attract tourists, and provide habitat for wildlife; and they also catch fire and endanger homes and lives during the annual forest-fire season. Talking about trees in Kalispell means talking about livelihoods and lifestyles, and the valley’s different interest groups are like sticks dangerously rubbing together in its drought-plagued forests.

Enter Stokes, radio host and human blowtorch. On environmentalists, Stokes has this to say: “Eradicate ’em. Their message stinks. They’re destroying America. And it all came out of the Third Reich. You know, the Third Reich was born out of the environmental community. I don’t make it up. It’s there.” Stokes attends town meetings, holds rallies, and burns green swastikas to protest what he sees as the tyranny of liberals, the U.S. Forest Service, immigrants, the government, and, of course, the people he refers to as “eco-Nazis” and “green Nazis.”

John Stokes prepares to burn a

swastika to draw attention to

“green Nazis.”

Photo: Montana Human Rights Network.

“John Stokes came to this valley and all of the sudden the people had a way of telling the truth,” says one timber worker featured in the film.

Clearly, Stokes and his listeners are angry. They’re angry at the Forest Service and the more uncompromising environmentalists for not letting loggers thin the forests in a way that will (they think) boost the flagging Montana economy and prevent fires. They’re angry about losing their timber-industry jobs. They’re angry about watching property values soar as millionaires buy weekend ranches in the valley.

During forest-fire season, when the valley’s residents are at their most vulnerable, Stokes’ provocations are strongest. “Anybody who’s ever written a check to the Sierra Club, the Nature Conservancy, Audubon, Citizens for a Better Planet,” he says, “hope you’re happy with yourself, ’cause we blame you.” Stokes warns his listeners to be careful, because “there are eco-arsonist terrorists out there.” He holds up a copy of an Earth Liberation Front manual and tells the camera, “They just had a terror training camp in Missoula in June.”

It’s not true, but it doesn’t matter: with his rants, Stokes has placed environmentalism squarely in the middle of the most charged discourse in post-9/11 America — the one revolving around the word “terrorism.” And while Stokes seems extreme, these days, he’s not the only one warning of an alleged link between environmentalists and terrorists. Joe Friday is too.

Hummers: innocent victims?

Photo: FBI.gov.

Fed Up

On June 21 of this year, FBI Deputy Assistant Director for Counterterrorism John Lewis called eco-terrorism one of the top domestic terrorist threats in the U.S. One month earlier, he’d made similar statements before a congressional committee. The FBI claims that 1,200 acts of eco-terrorism have taken place since 1990, causing over $110 million in property damage. Although ELF has said that it has never and would never target humans, the FBI is worried that might change. It has decided that ELF and the Animal Liberation Front pose a threat comparable to militias of the Timothy McVeigh stripe (whose numbers have fallen but whose threat remains significant [PDF], especially in Montana), and to white supremacist groups (whose numbers are rising, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center). Ironically, the Flathead Valley was home to one of the more notorious militia groups, Project Seven, which in 2003 was found with a cache of arms and a hit list of government officials.

The FBI says its concern is based on the fact that eco-terrorists are currently the most active of domestic terrorism groups. But when I spoke with FBI spokesperson Bill Carter, he was unable to detail the nature of the 1,200 “acts,” how many had occurred in each of the past few years, or how many people have been involved in committing them (although Lewis’ testimony says about 150 cases are currently under investigation). Even the top brass at the FBI seems confused about the extent of the threat. In February, FBI Director Robert S. Mueller III testified before the Senate Committee on Intelligence that major incidents of eco-terror had actually declined in 2004.

Meanwhile, Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) recently published a policy paper [PDF] that questioned why a draft of the 2005 terrorism priorities of the Department of Homeland Security reportedly did not mention right-wing terrorist groups (such as militias), while eco-terrorism was placed front and center. Thompson asked to testify before a May congressional panel that discussed eco-terrorism and threats to the nation’s infrastructure, but his request was denied by the panel’s chair, Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.). It was only the second time in history, according to a Democratic spokesperson for the House Committee on Homeland Security*, that a member of Congress had not been given the privilege of making remarks before a panel.

According to the Associated Press, Inhofe said he hoped to investigate how ELF and ALF raise money and support from “mainstream activists.” “Just like al-Qaeda or any other terrorist organization, ELF and ALF cannot accomplish their goals without money, membership, and the media,” the AP quoted Inhofe as saying.

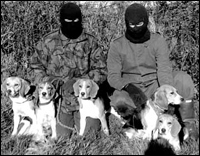

Now what self-respecting terrorist

would rescue cute li’l puppies?

Photo: arkangelweb.org.

It’s not that Thompson — or anyone, for that matter — is defending acts of terrorism on behalf of the environment. (Thompson has denounced ELF and ALF, as has every major environmental group.) It’s that they are trying to figure out how and with what consequences environmentalism and terrorism got coupled together in the first place. Yes, some expensive and illegal acts are committed in the name of the environment; and yes, the framework of terrorism is an easy and useful one for the FBI and the DHS to use when handling those incidents. (By calling ecological sabotage “terrorism” as opposed to arson or vandalism, federal officials are given slightly greater powers in investigating and bringing perpetrators to justice.) But what does it mean for environmentalism when the whole movement is defined by its margins? And what does it mean for the nation and the world when language is used so loosely even as last week’s attacks in London make the danger of real terror tragically plain?

For some, broadening the term “terrorist” to include organizations like ELF is bad for both environmentalists and for our sense of what real terror is. “These people are not environmentalists, they’re arsonists,” says Eric Antebi, a Sierra Club spokesperson. Antebi also rejects the idea that ELF’s actions constitute real terrorism. “Eco-terrorism is not a legitimate phrase — it cheapens what real terrorism is. We have seen in this country the real forms that terrorism takes,” he says.

However atypical ELF and ALF may be of environmentalism, they have come to characterize the movement for many on the right, in Congress, and in law enforcement. The backdrop to this development, of course, was September 11, 2001. First of all, 9/11 solidified the power of a government that also happens to be anti-environmentalist. Second, because of a (perhaps justified) national state of paranoia, 9/11 complicated the use of a tool that has been always essential to the environmental movement: direct action.

“We used to put banners on bridges, banners on big monuments,” says John Passacantando, executive director of Greenpeace USA. “When people are worried about this kind of structure, you don’t see us doing that. Our direct actions always have to be in the tone and the temper of the time.”

The FBI insists it distinguishes groups like ELF and ALF from the rest of the environmental movement, and is committed to the lawful expression of free speech. But the government has occasionally raised the specter of terrorism to support its cause, even if it meant darkening the name of mainstream environmental groups. In a widely publicized 2003 case in which Greenpeace activists boarded a ship carrying illegal mahogany from the Brazilian Amazon bound for the U.S., the Department of Justice seemed so bent on prosecuting the environmental group that it dug up an obscure 1872 law prohibiting “sailor-mongering.” Greenpeace’s Passacantando says that during the trial, federal prosecutors regularly referred — directly and indirectly — to 9/11. (At one point, he says, federal prosecutors stood a scale model of the ship on its aft next to two other scale models: a skyscraper that looked like one of the twin towers, and a 747.) “Even with Greenpeace, a group that’s been doing nonviolent action for 30 years, they tried to make us look like terrorists,” he says. The case was thrown out of court.

Meanwhile, few seem to be paying attention to another kind of eco-terror. For many environmentalists and politicians, eco-terrorism used to mean blowing up a nuclear plant or poisoning a water system — actions that, unlike those of ALF or ELF, would deliberately put thousands or tens of thousands of lives at risk. Ironically, the post-9/11 crackdown on terrorism has stifled some of the organizations that used to draw attention to those threats. “Greenpeace used to go into nuclear plants, chemical plants,” Passacantando says. “We don’t do that anymore. We could — the security there is terrible. We put out reports instead.”

In a country where up to 80 percent of the citizenry professes some support for environmental protections, the environmental movement has somehow found itself on the fringes of the political discourse. In part, that’s because people like Rush Limbaugh and John Stokes have been effective at reducing the image of the environmental movement to a group of little green Hitler elves, running around blowing things up.

Clearly, destroying private property in the name of the environment is a crime, and the few activists doing so are a proper focus of law enforcement. But equating ELF and ALF direct actions with the deadly attacks of terrorist groups fuels the anti-environmental rhetoric of the right and irresponsibly conflates two very different kinds of criminal activity. What we lose in the process is our grasp on both the real nature of environmentalism and the real nature of terrorism. For someone like John Stokes, who is only interested in exploiting his listeners’ fear, the difference doesn’t matter. For the rest of us, it should.

Correction, 11 Jul 2005: This article originally cited a Democratic spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security; it should have cited a Democratic spokesperson for the House Committee on Homeland Security.