This story was originally published by HuffPost and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Ben Lecomte is swimming through tons of plastic. Pieces of it have gotten stuck to his face. He’s passed abandoned fishing nets that tangle and kill wildlife. He’s held pieces of broken storage crates blooming with algae and barnacles. And he wants us to see it all — so we know what we’ve done to the planet.

In June, the athlete and environmental advocate embarked on a swim through a highly polluted stretch between Hawaii and California. By September, he hopes to traverse 300 nautical miles of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the world’s largest accumulation of marine plastic debris. It’s an area that’s not well understood, despite recent media attention to the growing problem of plastic waste.

A member of the Vortex Swim team photographs an abandoned fishing net bobbing near the surface. @JoshMunoz / Vortex Swim

Lecomte’s effort, called the Vortex Swim, is part adventure, part research experiment. His team — scientists, sailors, and photographers — don’t guide him in a straight line toward his final destination; instead, they direct him toward areas where they expect to find floating trash.

For instance, the University of Hawaii, one of the partners on this project, already has tracking devices out there, attached to large pieces of debris, and the Vortex Swim team sends Lecomte to investigate those spots while he swims. The team is also collecting data for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, and several other organizations.

Lecomte setting off. @osleston / Vortex Swim

What kinds of plastic trash have they found so far? Lots of different stuff, says Lecomte, who boards his team’s boat to rest in between bouts of swimming. “The most common pieces we find generally have some connection to the fishing industry. Fish crates, buckets, and lots of ghost nets,” he told HuffPost by email. They’ve also found household items, like soda bottles, CD cases, and plastic bags — even a laundry basket.

The team is documenting its progress on Instagram. One of the most striking things about its photos is how infrequently large plastic objects are found. But don’t be fooled — the water is teeming with debris, Lecomte told HuffPost.

“This is one of those issues that cannot necessarily be seen with the naked eye,” he said.

Plastics that end up in the ocean tend to break apart into small pieces that are practically microscopic. Much of the debris Lecomte encounters is barely visible. Every day, his team trawls the water with a net to collect plastic particles as he swims — they always find some. Lecomte isn’t usually aware of these tiny pieces while he’s swimming, although once he arrived back on the boat with a small chunk of plastic stuck to his face.

Each day, the Vortex Swim team puts a net into the water for 30 minutes to see what plastic particles they can find. They never come up empty. @osleston / Vortex Swim

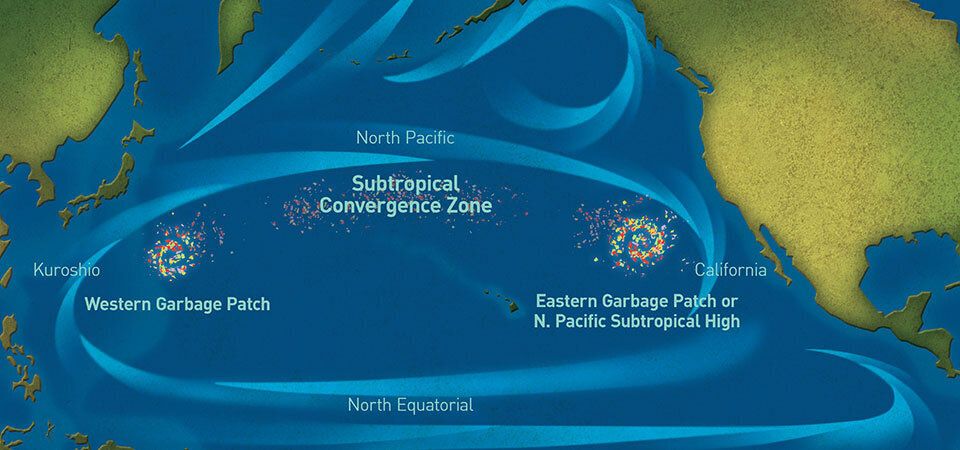

The world’s oceans contain an estimated 150 million metric tons of plastic garbage. It can be found floating at various depths and resting on the seafloor. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is just one of five major convergences that occur around the world where ocean currents create higher concentrations of trash. These so-called garbage patches don’t have clearly defined borders: They shift and change all the time. They’re not dense enough to walk on top of or see from space.

Lecomte says people shouldn’t think of garbage patches as floating islands of trash. Instead, he describes them as a “smog of particles circulating with the currents.”

The Pacific Ocean is home to two such garbage patches: one in the South Pacific and one in the North, where Lecomte is exploring. The North Pacific patch is particularly difficult to study because it covers a sprawling area — from California to Japan — and consists of two distinct sections, between which currents carry plastic particles back and forth over great distances. Lecomte’s team is focusing only on the eastern section, which is estimated to be twice the size of Texas.

A rendering of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which is spread over a massive area of the North Pacific between California and Japan. Lecomte and his team are currently navigating the eastern portion. NOAA

Lecomte and his team have been most surprised to see how wildlife interacts with the floating plastics. Whenever they locate a large piece of debris, they usually find that a small ecosystem has popped up around it. Plants and barnacles attach to the plastic’s surface, while fish take shelter in the shadow the item casts.

“These drifting homes wander the ocean currents, collecting larvae and eggs as they go,” Lecomte wrote on Instagram last month.

Abandoned fishing gear and household plastics can entangle and strangle marine animals. In addition, scientists know that fish eat tiny pieces of plastic, as well as fibers that shed from synthetic clothing. Baby fish are known to mistake plastic particles for food during their first days of life. The Vortex Swim crew, which catches fish to supplement their food on the journey, recently found shards of plastic in the belly of a mahi-mahi. It is unclear what effects small pieces of debris have on the animals that eat them or how they affect the rest of the food chain.

A member of the Vortex Swim team holds a laundry hamper or storage basket covered in aquatic life. @DWLangdon / Vortex Swim

The Vortex Swim team often debates what to do when they find a plastic item that has creatures living on or around it, Lecomte told HuffPost. “Do we leave it to save those animals now? Or take it to stop it from breaking up into smaller and smaller fragments potentially hurting more animals in the future?”

The team ultimately leaves behind a lot of things they find. After all, Lecomte told HuffPost, this is not a cleanup mission, and space is limited on their boat.

“If we collected every item, we would need a container ship to house it,” he said.

Ocean cleanups are extremely complex and expensive. It would take 67 ships one year to recover less than 1 percent of the debris in the North Pacific, according to NOAA.

There are several trash-collecting efforts underway in the Pacific. The most famous, the Ocean Cleanup system, was designed by 24-year-old Boyan Slat and floats with the currents to catch debris near the surface. The first iteration of this system broke in December, spilling trash back into the water before being towed to shore in Hawaii. The Ocean Cleanup deployed a new device in June.

Ocean researchers and advocates say that although attempts to clean up marine trash can be worthwhile, a better long-term solution is to focus on plastics before they escape into the environment.

Lecomte finds a plastic crate surrounded by fish. @osleston / Vortex Swim

“The best way to prevent large accumulations of debris from getting larger is to stop debris from entering the ocean in the first place,” said Nancy Wallace, director of the marine debris program at NOAA.

Lecomte, for his part, says people should focus on reducing the production and consumption of plastics.

“The only sustainable way to deal with this global issue is to stop the problem at its source: to change our habits on land, stop using single-use plastic, and when possible use alternatives to plastic,” he told HuffPost.

Last year, Lecomte planned a record-breaking swim from Japan to California but had to abandon the attempt before the halfway point because of technical difficulties with his support boat. He encountered ocean plastics every day during the trip — far more than expected — and when he and the team decided to finish their transpacific voyage this year, they chose to focus their efforts on raising awareness around plastic pollution instead of on breaking records.