Most of us know what torture it is to be a wallflower, so it’s hard not to feel at least a slight frisson of sympathy for the nuclear industry. Once considered “most likely to succeed,” this promising power source found itself stumbling in the 1970s. It was bad enough after Three Mile Island in 1979 — particularly when Jane Fonda got to work in The China Syndrome. But this wallflower status was taken to an altogether different level in 1986, in the wake of an event whose ongoing repercussions will provide some of next year’s great news hooks.

She’ll be back on her feet in no time.

Photo: iStockphoto.

After Chernobyl, nuclear folk worldwide found themselves not just wallflowers, but actively disinvited wherever people came together to dance around the subject of sustainable energy. It was rather like Cinderella’s coach and horses turning back into something a lot more mundane. And when the ill-fated Chernobyl site was shut down for good in 2000, some critics hailed the closure as the beginning of the industry’s end.

Was it? Hardly — and not just because of the high-level waste that will undoubtedly outlive our civilization by several hundred thousand years. In fact, this industry that was once consigned to the corner seems set to become the belle of the business world’s ball.

Sting Your Partner

The sheer horror of the statistics that will no doubt be rolled out in 2006 would give even a nuclear engineer pause. Take thyroid cancer, normally a rare disease, with just one in a million children falling victim; a third of children who were younger than four when exposed in the main Chernobyl fallout zone are thought likely to develop the disease. In Belarus — where 60 to 70 percent of the fallout landed, contaminating some 25 percent of the country’s farmland and forest — nearly 1,000 children have come down with thyroid cancer, compared to seven in the 10 years before the accident.

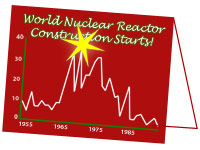

This type of thing has made the nuclear industry a darned unattractive prospect for NGOs and anyone else wanting to fill their partnership dance card. Today, anti-nuclear folk point with glee to the trend line for reactor construction starts — which, having sketched the spiky outline of a pine forest from the mid-1960s to mid-1980s, plummeted over the subsequent 20 years to the stuttering outline of melting snowdrifts. If the message weren’t so gloomy for the nuclear folk, it might have made a nice Christmas card.

But irony of ironies, the industry is back, thanks in great part to environmental concerns. In 2004, for example, greens were shocked when one of their idols — James Lovelock of Gaia hypothesis fame — warned that only a massive expansion of nuclear power would save our current industrial civilization from rapidly advancing climate change. The peak-oil debate has been another driver, and it’s all left environmentalists wondering: should we open our arms to the industry?

It’s a complicated question. Much of the 20th century was spent in a hate-love-hate relationship with nuclear technology, mainly thanks to the shadow of the A-bomb. One of us remembers his father shipping off in 1957 to fly monitoring missions around the British H-bomb bursts above, yes, Christmas Island. On the upside, we were told we were going to zoom around in nuclear cars, trains, and planes. Energy too cheap to meter, we were promised, and a glowing cornucopia of atomic toys and gadgets. Now, again, nuclear is being dangled as the great, white-hot hope.

Even as today’s giant companies like BP and GE begin to tilt to windmills and other renewable-energy technologies, countries like Indonesia and Vietnam are thinking seriously of going nuclear. The World Energy Council claims that the industry is “poised to expand its role in world electricity generation. Plant life will be extended in some markets, such as Finland or Sweden; new plants will be built in Asia; governments and voters will accept the inevitability of new nuclear power stations in Europe, Africa, North America, Latin America, and even the Middle East.”

If the Slipper Fits …

So the question arises: is the environmental movement in danger of letting its allergic response to nuclear power blind it to a scenario filled with new technologies and players? If commercial opportunity — like some Prince Charming — does come a-knocking at the nuclear industry’s door, we will desperately need to know who the Ugly Stepsisters are, and whose foot we might be happy to see the slipper fit.

What do we really know about the nuclear activities of companies like GE, TVO, or Westinghouse? If we ignore the whole sector and some form of nuclear renaissance does occur, are we in danger of losing the chance to shape the industrial consequences? (Full disclosure: SustainAbility was founded the year after Chernobyl, and while we have always insisted that we will not work with the nuclear industry, we have been working recently in non-nuclear areas with a French company that has some nuclear involvement.)

It’s truly a case of the glass being half empty or half full. Some of the world’s biggest users of nuclear power are signaling that they will have to decommission many of their plants in the coming years. While anti-nuclear activists assume renewables and energy efficiency will fill that gap, the nuclear industry sees such closures in an increasingly carbon-constrained world as huge potential opportunities to build new reactors.

Common sense would suggest that we should avoid even thinking about the nuclear option. Just as the 20th anniversary of the Bhopal disaster in 1984 turned up the heat under the international chemical industry, 2006 will do the same for nuclear. And yet, we can’t get out of our minds the argument of some industry observers that the debate may well change over the next decade — from questions about whether or not reactors should be built to what sort of reactors should be built.

Ultimately, the swing factor in determining our energy future may not be the Lovelocks or the anti-nuclear activists of this world, but China. If Hollywood ever makes China Syndrome 2, it’s conceivable that the story line would be about Chinese engineers helping to save the planet from melting down. While Western power producers continue to favor slight tweaks on conventional large-scale reactor designs — and as a result will likely keep trying to shoehorn their big-footprint feet into environmentally constrained shoes — China is different. With a fast-growing appetite for energy and a serious dislike of the idea of being in thrall to anyone else for access to said energy, China is beginning to develop a taste for a very different form of nuclear technology.

Get ready to hear a lot more about “pebble-bed modular reactor” designs, either as a stepping stone or as an ultimate destination. First developed in Germany, the technology is winning growing support in countries like South Africa and France. These reactors are, among other things, a fifth the size of conventional reactors, much less capital-intensive, and much less prone to meltdowns. For countries that fear overdependence on the West, they also have the added advantage that they don’t need Western-style fuels or refueling services. In short, they have all the makings of a potential Cinderella story.

What’s the Mandarin for “go figure”?