Can soda taxes actually get people to cut back on an unhealthy habit, or do they just keep on drinking while handing money over to the government? The answer matters to the handful of cities that have or are considering a soda tax. A new study on Berkeley’s tax on sugary beverages is good news for supporters of the strategy: Researchers found a 21 percent decline in soda drinking in low-income neighborhoods.

That’s huge. A similar tax in Mexico led to a 12 percent decline, and another in France reduced consumption by 7 percent.

Why is Berkeley’s soda tax, which started in March 2015, so different? Residents could be more sensitive to price increases, or influenced by the anti-soda campaign. As this was based on pre- and post-tax interviews, it’s also possible that people fudged their answers to sound healthier. Anyone who has ever been to the dentist knows the powerful urge to lie about flossing habits.

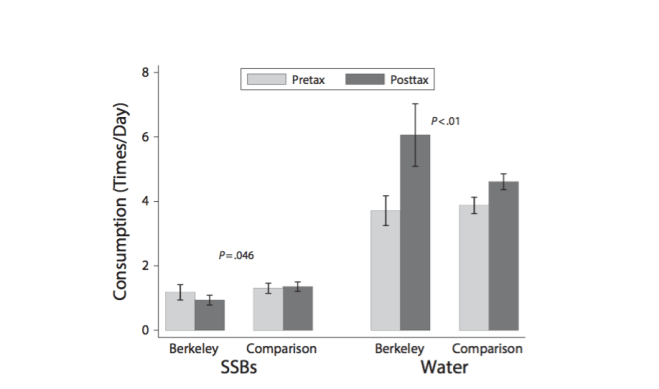

But the researchers also interviewed people in the nearby cities of Oakland and San Fransisco and those residents said they were drinking more soda. The Berkeley residents also reported drinking more water, suggesting a healthy substitution of beverages.

Sugary beverages (SSBs) and water consumption in Berkeley and comparison cities (Oakland and San Francisco).

It would be great if someone could back this survey with hard data showing a decline in sales. Still, this is the best evidence yet on soda tax efficacy in a U.S. city.