The burgeoning love affair between Americans and renewable energy is turning into a love triangle with natural gas.

That’s one of the findings from the U.S. Energy Information Administration recently released annual forecast. The projections, widely used by bureaucrats and business people, show renewables and gas becoming the main source of our electricity and sales of gasoline-burning cars declining. But greenhouse gas emissions aren’t expected to fall much. What gives?

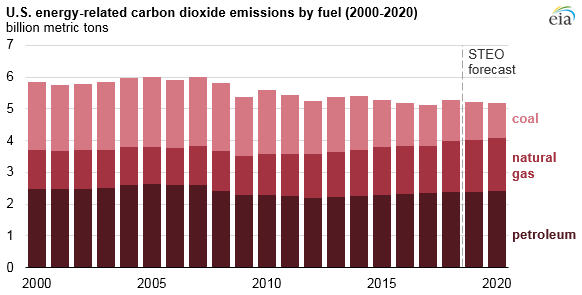

One reason: Even though coal emissions are falling, emissions from natural gas are making up the difference. And the country keeps using more energy. Last year for instance, according to another recent EIA report, U.S. emissions ticked up as more Americans turned up their air conditioners and heaters to stay comfortable in extreme weather.

EIA

It’s an open question whether things will play out this way, of course. The EIA’s predictions have consistently underestimated the growth of renewable energy (more on the caveats below). In 2009, for instance, the EIA expected wind and solar to take 20 years to reach 56 gigawatts of capacity. Instead, thanks to a suite of new policies from President Barack Obama’s administration, the U.S. built 89 GW in just six years. As Mike Grunwald from Politico put it, “Oops.”

Still, this particular crystal ball provides a solid estimate of the country’s current trajectory, because its forecasts are built on recent trends. A quick perusal of the following charts will give you a sense of how much climate progress the country is making.

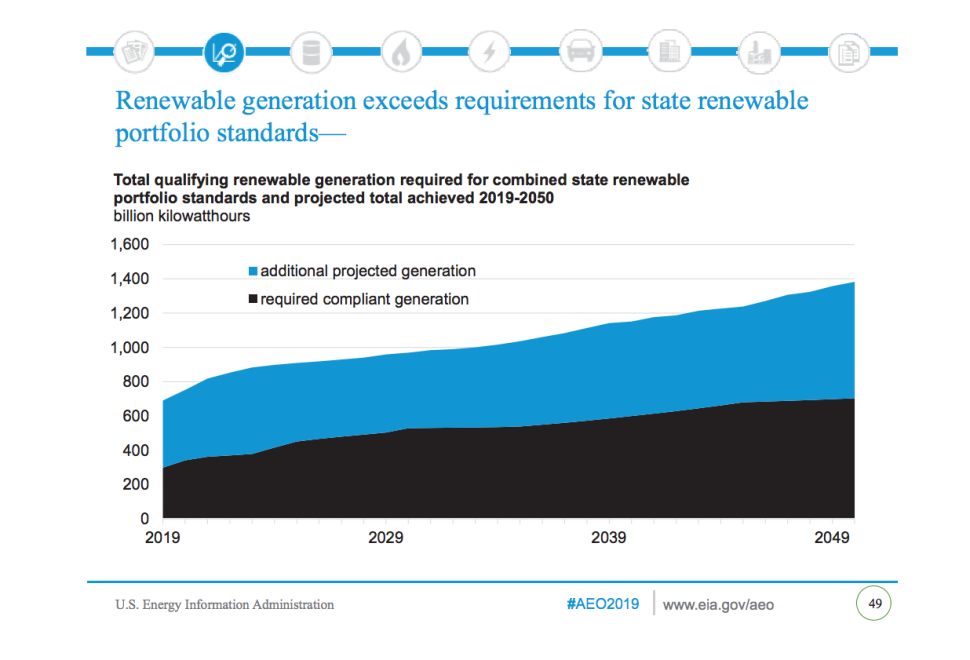

First, the good news. Renewable energy is poised to grow so robustly that it would easily exceeds states’ carbon-cutting goals.

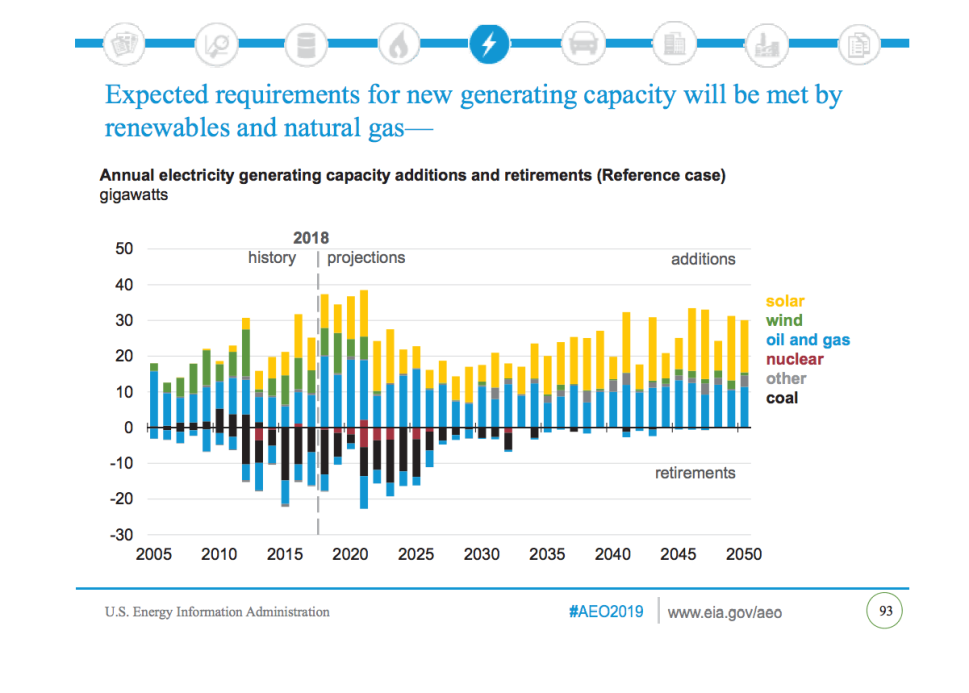

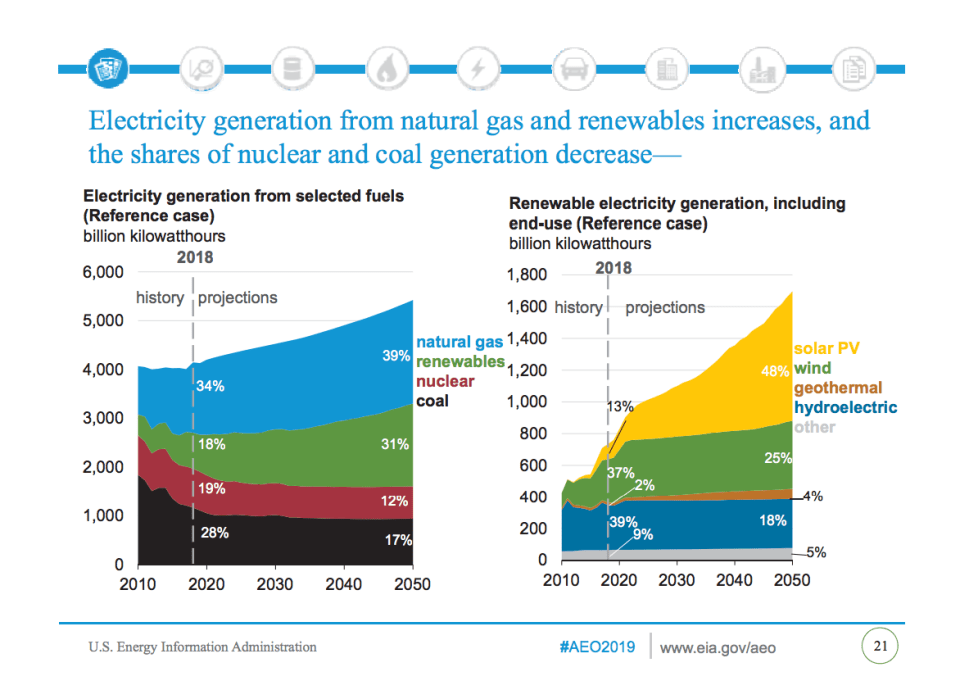

For the foreseeable future, the United States will be turning to solar panels, wind turbines, and gas plants to generate electricity, according to the forecast, while shuttering nuclear, oil, and coal plants.

All this points to renewables and natural gas pairing up to provide most of our electricity. That makes some sense, because renewables play well with gas. Gas plants are easy to control — they can ramp up and down cheaply. And renewables depend on nature (the rising sun and the gusting wind) so need a partner to fill in the gaps.

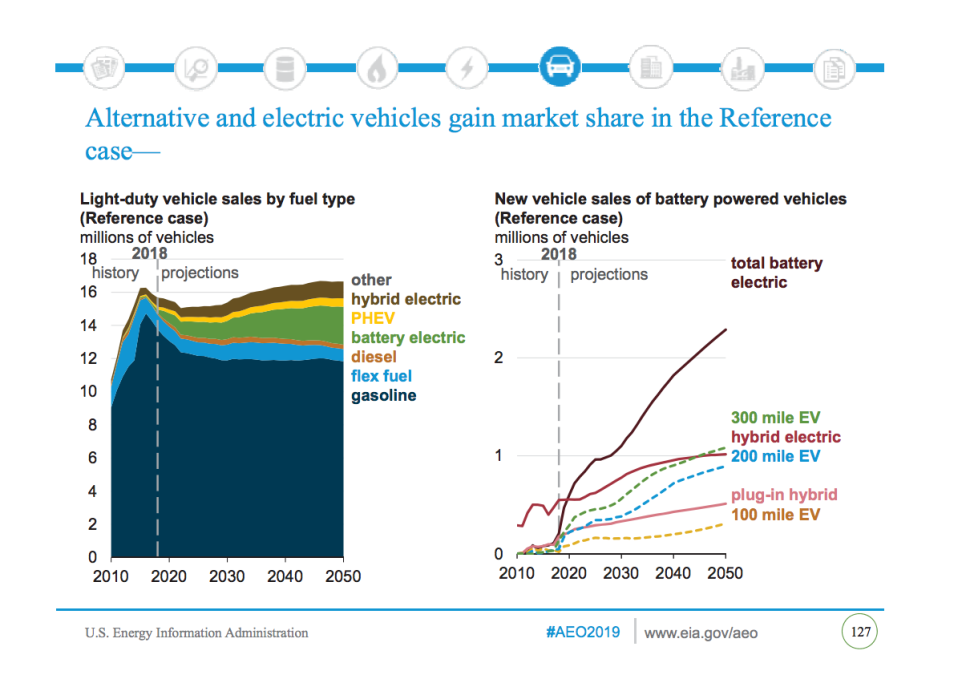

Electricity is just one slice of our oh-so-yummy energy pie. But that slice should grow as more people begin to buy electric cars. The EIA projects that cars with internal combustion engines will lose market share in the coming years. But it expects that decline to level off shortly after 2020.

EIA

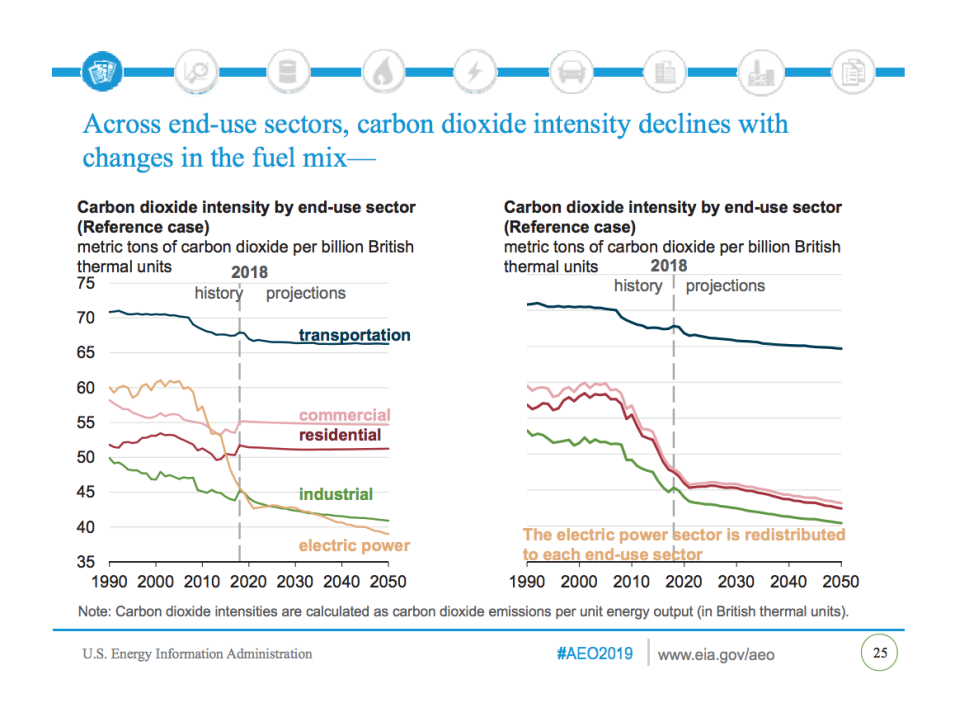

When you look at the other sources of energy demand, like industry and buildings, the EIA sees something similar happening: Emissions are flat, or slowly falling.

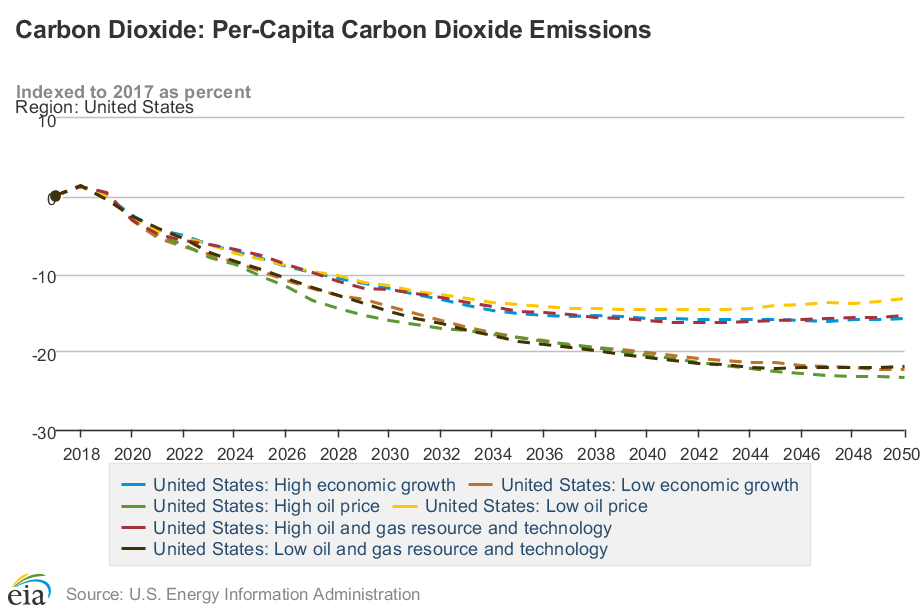

Add it all up and you get per-person emissions declining, but declining pretty darn slowly. Even if oil prices spike, the EIA expects just a 25 percent decline in per-capita emissions by 2050.

There are caveats here. The energy analyst Alex Gilbert, co-founder of the energy-research company SparkLibrary, thinks it’s also unrealistic to expect coal to pull out of its death spiral (the EIA sees that plunge mellowing into a glide), and points out that EIA is predicting that folks will pretty much stop building wind turbines, which seems… unlikely.

Wind, however, is projected to die an early and industry-shattering death. In only 1 scenario does wind capacity see any growth post 2020. EIA also projects 0 MW of off-shore wind. Both of these projections are in significant conflict with industry expectations pic.twitter.com/yGOcg74bqI

— (((Alex Gilbert))) (@gilbeaq) January 24, 2019

What’s more, the EIA’s expectations for a shift away from gas-powered cars lag far behind estimates by others. The EIA has also consistently underestimated the growth of renewable energy, and it may do the same with the growth of electric vehicles.