When I was growing up in central Ohio, school began right after Labor Day. This was advantageous compared to today’s August start, and not just because of the longer summer break. The extra time also allowed the black walnuts to ripen just in time to give us something to hurl at each other as we walked to school that first morning.

Front-yard bounty.

They littered the ground all through the streets on my route to elementary school. It was customary to announce your approach behind fellow students by pelting them with the large green orbs. The nuts seemed to have been created especially to be launched by nine-year-old boys. Two inches across, perfectly round, and with a slightly rough texture that we imagined made it possible to throw curveballs with them. The ripest ones were best because, if they could be made to explode on impact, they left an indelible stain and a smell that followed the target around school all day. I have been both victim and perpetrator numerous times.

Today I use the sweetmeats for far more peaceful purposes such as cakes, breads, and salads, though when no one is looking I occasionally test my aim out on the flood plain behind my house. Still haven’t mastered that curveball.

If you are fortunate enough to have one or two of these magnificent trees in your neighborhood, this is the time of year when you want to be trying to beat the squirrels to the walnuts. Of course, they have the advantage of being able to climb up into the trees and out onto the smallest branches pursuing their winter stashes, but we have the benefit of opposable thumbs and buckets to carry many more at once. So it’s a fair fight.

Before you gather too many, break a couple open with a hammer to make sure the kernels are full (those are the parts we eat, but don’t eat them yet). Crops from even the best trees are unpredictable, and sometimes the kernels fail to fill. Trees that supplied bushels one year may yield only a few good nuts the next, so best to check before you go through all the effort.

The best nuts are picked from the trees, but most people wait for them to fall to the ground — it’s just easier that way. Choose only ripe nuts, which can be identified when their color changes from bright green to a yellowish shade, and the husk can be dented with your thumb.

A few pointers about husking them: Wear gloves and an apron, and do it outside. Some people find the pungent smell objectionable, though I kind of like it despite the aforementioned childhood trauma. The staining reputation of the walnut juice, though, is legendary and well deserved.

Are you nuts? Black walnuts ripen.

Remove the hulls with a hammer or by stomping underfoot (don’t use the running-over-with-a-car method you may have heard of) and wash the nuts thoroughly with a garden hose. Lay them out to dry on old window screens in a cool, dry, well-ventilated place (I use my garage). They will be ready in about two or three weeks, and you can tell they are well cured by cracking one or two, and checking the kernels snap crisply.

As for storage, the University of Minnesota Extension Office advises, “After curing, store unshelled nuts in a well-ventilated area at 60 degrees F or less. Cloth bags or wire baskets allow adequate air circulation and discourage development of mold. Try to keep the relative humidity fairly high, ideally about 70 percent. Nut shells will crack and the kernels spoil if nuts are stored in too dry an area.” Really, though, just put them in your hall closet.

The walnuts I didn’t throw at my friends 30-odd years ago (some might say 30 very odd years) always ended up on our holiday table, in a plastic bowl fashioned to look like a slice of a walnut log, and my father would crack the shells and fish out the meats for the kids. I can still taste them.

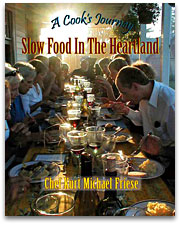

A Cook’s Journey: Slow Food in the Heartland, by Kurt Michael Friese.

Shiitake and Wild Black Walnut Tartare

In my new book, A Cook’s Journey: Slow Food in the Heartland, I profile Dragonfly Neo-V, the organic, vegan restaurant of Chef Magdiale Wolmark in Columbus. He shared a recipe for Shiitake and Wild Black Walnut Tartare.

Magdiale grows his own shiitake mushrooms for this dish on a log in the back yard, and forages for the black walnuts that are prolific in central Ohio.

This is a great dish to serve at your next party — everyone will be pleased with the combination of intense flavor & high nutritional value, something true of all the food at Dragonfly Neo-V.

Ingredients

1 cup fresh shiitake mushrooms, rinsed, stemmed and chopped

1 tablespoon fresh parsley, chopped

1/4 cup wild black walnuts

1 tablespoon tamari*

1/2 teaspoon minced ginger

1 pinch salt

1 dozen capers

1 teaspoon Walla Walla onion (or other very sweet onion), diced

3 homemade pickled vegetables such as okra, green cherry, or “bread & butter”**

1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

6 slices of of good, crusty bread, drizzled with sesame oil and grilled

In a food processor, pulse the walnuts until they are very finely ground, but not quite a paste. Add parsley and shiitakes and pulse 6 or 7 times until shiitakes are minced. Very important to stop here — as mushrooms lose water, the mixture will begin to bind. Add ginger and drizzle in tamari while pulsing 2 or 3 more times.

Remove mixture and form into a patty, served with condiments and toast.

*Tamari is a form of soy sauce, originally a byproduct of making miso. It is readily available at any Asian market, and now even many mainstream grocery stores.

**Home pickling is fairly easy, but if you must substitute with prepared ones, choose interesting flavors from a purveyor you trust.