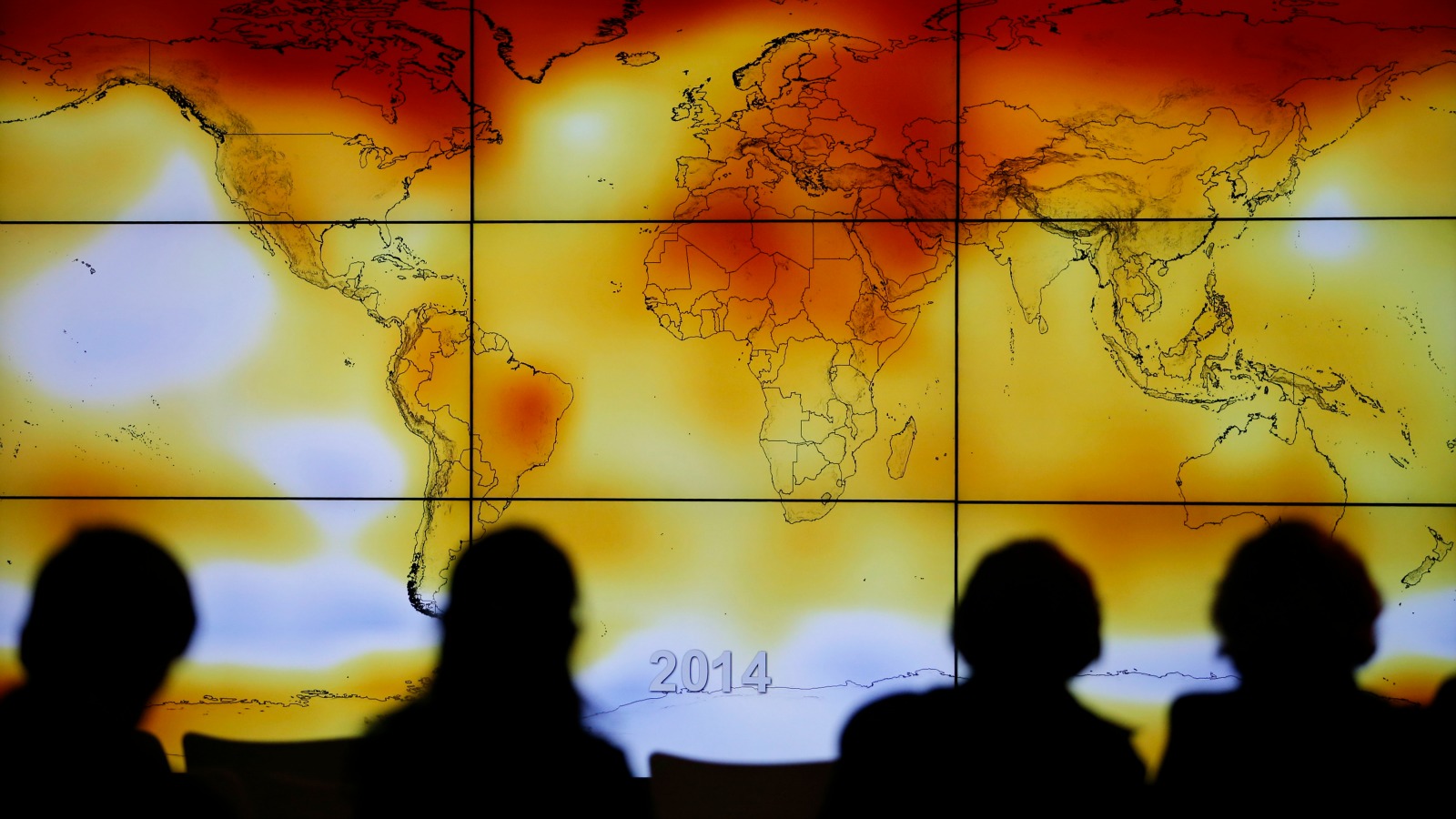

Cyclical changes in the Pacific Ocean have thrown Earth’s surface into what may be an unprecedented warming spurt, following a global warming slowdown that lasted about 15 years.

While El Niño is being blamed for an outbreak of floods, storms, and unseasonable temperatures across the planet, a much slower-moving cycle of the Pacific Ocean has also been playing a role in record-breaking warmth. The recent effects of both ocean cycles are being amplified by climate change.

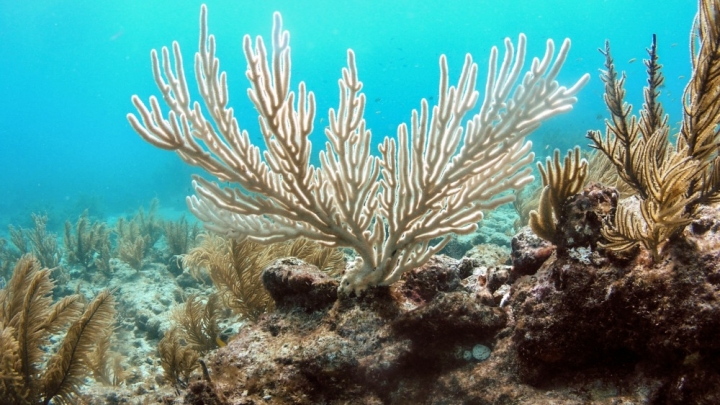

High temperatures are bleaching corals, such as this bent sea rod off Florida.U.S. Geological Survey

A 2014 flip was detected in the sluggish and elusive ocean cycle known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, or PDO, which also goes by other names, including the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Despite uncertainty about the fundamental nature of the PDO, leading scientists link its 2014 phase change to a rapid rise in global surface temperatures.

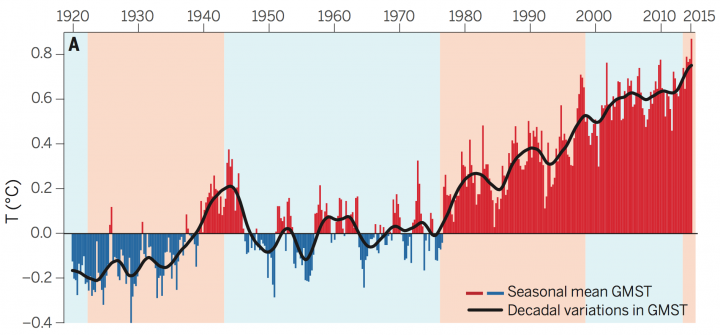

The effects of the PDO on global warming can be likened to a staircase, with warming leveling off for periods, typically of more than a decade, and then bursting upward.

“It seems to me quite likely that we have taken the next step up to a new level,” said Kevin Trenberth, a scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

The 2014 flip from the cool PDO phase to the warm phase, which vaguely resembles a long and drawn out El Niño event, contributed to record-breaking surface temperatures across the planet in 2014.

The record warmth set in 2014 was surpassed again in 2015, when global temperatures surged to 1 degree C (1.8 degree F) above pre-industrial averages, worsening flooding, heatwaves, and storms.

Trenberth is among an informal squadron of scientists that in recent years has toiled to understand the slowdown in surface warming rates that began in the late 1990s, which some nicknamed a global warming “pause” or “hiatus.”

A flurry of recent research papers has indicated that the slowdown was less pronounced than previously thought, leading some scientists to renew claims that those nicknames are inaccurate and should be abandoned.

“The slowdown was not statistically significant, I suppose, if you properly take into account natural variability, which includes the PDO,” Trenberth said. “That’s sort of the argument that people have been making; that even if it was a little bit of a slowdown, or pause, or call it what you will, it’s not out of bounds, and as a result we shouldn’t really put a label on it.”

The approximately 15-year warming slowdown was linked to the negative phase of the PDO, which is also called its cool phase. That phase whips up strong trade winds that bury more heat beneath sea surfaces, contributing to extraordinary levels of warming recorded in the oceans. A similar phase led to a slight cooling of the planet from the 1940s to the 1970s.

Cold PDO phases have a blue background; warm phases are red.Science Magazine

“Last time we went from a negative to a positive was in the mid-’70s,” said Gerald Meehl, a National Center for Atmospheric Research scientist. “Then we had larger rates of global warming from the ’70s to the late ’90s, compared to the previous 30 years.”

“It’s not just an upward sloping line,” Meehl said. “Sometimes it’s steeper, sometimes it’s slower.”

The effects of the warm phase of the PDO and the current El Niño may be cumulative in terms of warming the planet. It also seems likely that changes in the ocean cycles are linked, with changes between El Niño and La Niña driving changes in the PDO cycle.

Or, perhaps the PDO doesn’t exist at all, other than as a tidy pile of data points, and it’s simply a manifestation of changes in the shorter-running cycle between El Niño and La Niña.

“There’s some debate about whether there is a low frequency oscillation — is there a distinct interdecadal oscillation?” said Penn State meteorology professor Michael Mann. “Or is what we call a low frequency oscillation just a change over time in the frequency and magnitude of individual El Niño and La Niña events?”

Regardless, “it seems pretty clear that we’ve transitioned from a time period where there was a prevalence for La Niña conditions,” Mann said. “Over the past several years we’ve been in the multi-year El Niño state, and it has culminated with an extremely large El Niño event.”

The future of PDO phases will not slow down or speed up the overall long-term rate of global warming. That will continue to rise with pollution levels. But scientists are expecting more intense heat during the months ahead, which should bring with it more wild weather.

“There are a lot of things in place that have locked us on course to have a really warm start to 2016,” said National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist Nate Mantua. “I have a hard time seeing how we’re not going to be looking at either record level or near-record level global mean surface temperatures for at least the first half of 2016.”