This story was originally published by the HuffPost and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

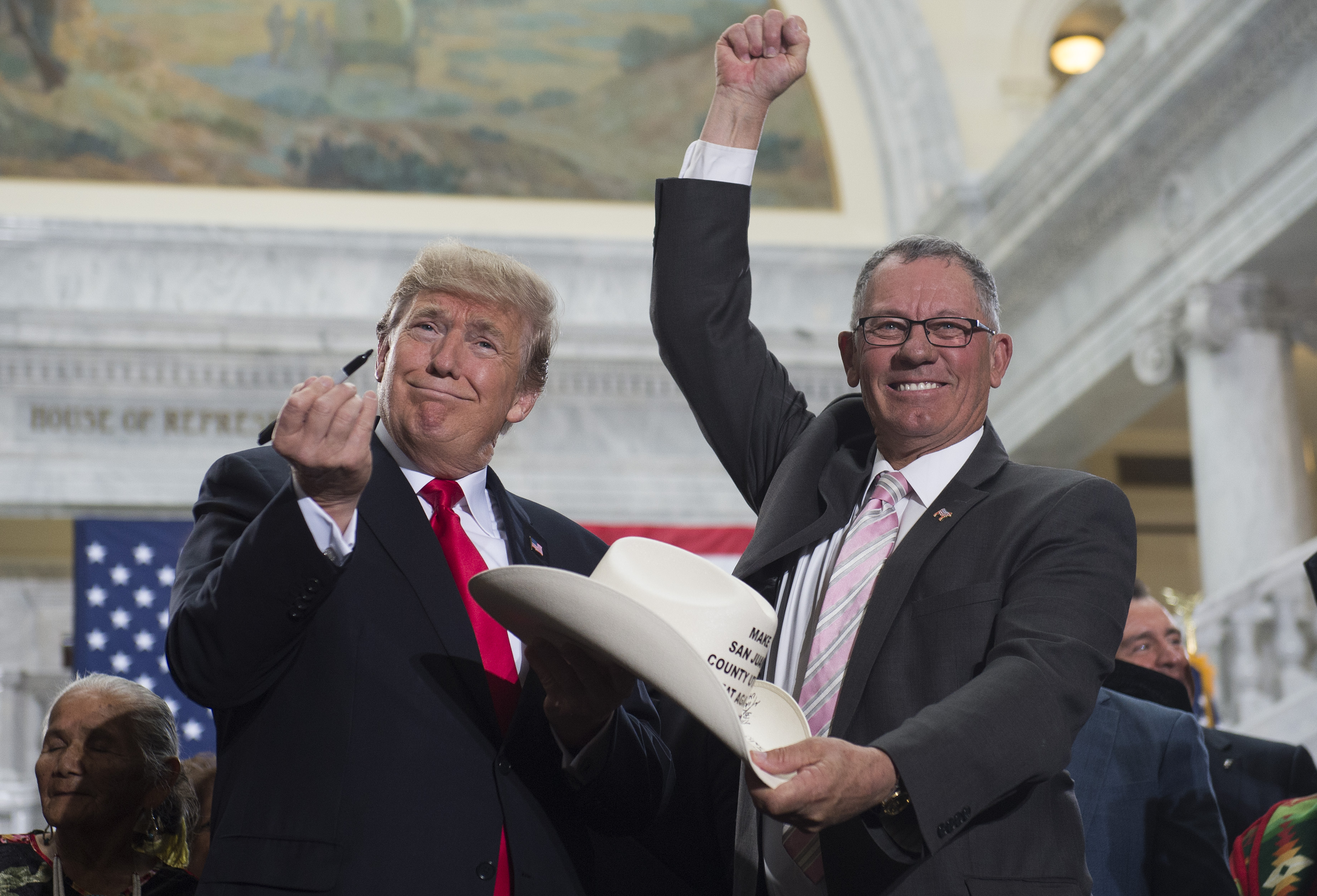

President Donald Trump, a self-proclaimed “loyalty freak,” found a loyal friend and unwavering supporter in former Senator Orrin Hatch, a Republican from Utah.

So when Hatch’s office sent a letter in mid-March 2017 requesting that the Interior Department shrink the boundary of Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument to free up fossil fuel-rich lands, as the New York Times revealed, the Trump administration sprang into action.

A little more than a month later, Trump signed an executive order calling for a review of more than two dozen recent national monument designations. It was clear that Bears Ears was the primary target. At the signing ceremony, Trump said he’d “heard a lot about” the 1.35 million-acre site in southeastern Utah and how “beautiful” the area is. He painted the Obama administration designation as a massive federal land grab. And he boasted that it “should never have happened” and was made “over the profound objections” of the state’s citizens, and that he was opening the land up to “tremendously positive things.”

He made no mention of the five Native American tribes that consider the area sacred and jointly petitioned for the monument’s creation. Instead, he thanked Hatch for his “never-ending prodding.”

“[Hatch] would call me and call me and say, ‘You got to do this,’” Trump said. “Is that right, Orrin? You didn’t stop. He doesn’t give up. He’s shocked that I’m doing it, but I’m doing it because it’s the right thing to do.”

Again, this was before former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke launched what he promised would be an objective, thorough review of recent monument designations; one he said would give all stakeholders a voice. In the end, Trump signed a pair of proclamations to cut more than 2 million acres from Bears Ears and nearby Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument — the largest rollback of national monuments in U.S. history. Seemingly every action leading to that decision suggested the outcome was predetermined.

On Wednesday, Democrats on the House Natural Resources Committee held an oversight hearing to examine what they described in a news release as Trump’s “illegal decision to shrink” the Utah sites. The event, titled “Forgotten Voices: The Inadequate Review and Improper Alteration of Our National Monuments,” featured testimony from several tribal leaders, the Utah state director of the Bureau of Land Management and other stakeholders. Zinke turned down an invitation to testify through his attorney, according to a committee spokesperson.

Representative Raúl Grijalva, a Democrat from Arizona and the committee’s chair, told HuffPost in a recent interview that Zinke created a culture at the Department of the Interior centered on “making life easier” for oil, gas, and mining interests at the expense of conservation and environmental stewardship. The monument rollbacks, he added, “epitomizes” that culture.

Grijalva echoed that sentiment during the committee’s hearing. He said the administration’s review was “hollow and improper” and gave industry “special consideration.”

“It is my firm belief that this was a predestined outcome and that everything that has occurred since then has been to justify that outcome,” Grijalva said. “I don’t think it’s justifiable.”

BLM directed to free up coal deposits

One of the biggest revelations about the administration’s motives came during Wednesday’s hearing, when Representative Jared Huffman, a Democrat from California, cited testimony from a BLM employee who said he was directed to redraw the boundary of Grand Staircase-Escalante to exclude coal-rich areas and to be no more than 1 million acres.

“The first area I was told to exclude from the boundary, with no discussion, was the coal leases from 1996,” the BLM mapping specialist told investigators at Interior’s Office of Inspector General, according to Huffman.

Huffman went on to reveal that the expert was told to carve out areas rich in fossils, the very resources the monument was established to protect.

“The big one was the paleontological resources — huge dinosaur area,” the BLM expert told investigators, according to Huffman. “These coal areas are all pretty high dinosaur resources areas. We were told they are out regardless.”

This testimony is included in an unredacted version of an OIG report release in January that concluded there is “no evidence” that Zinke gave retired Utah state Representative Mike Noel preferential treatment when he redrew the monument’s boundary.

Ed Roberson, BLM’s Utah state director, told lawmakers Wednesday that the review was open, fair, and thorough. Huffman told Roberson that the order given to the BLM mapping specialist “does not sound like an honest and exhausted process,” but rather “a pre-cooked decision to allow coal companies to mine this coal.”

In his final report to the White House, Zinke acknowledged the potential for mining coal in Grand Staircase-Escalante, noting that the site contains “an estimated several billion tons of coal.” Downey Magallanes, the daughter of a former executive of coal giant Peabody Energy, was a top Interior official who oversaw the Trump administration’s monument review. She left the agency last year for a job at oil giant BP.

Former Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke during a visit to Utah in 2017. George Frey / Getty Images

Zinke cozied up to monument opponents

In the week after Trump signed the orders threatening the future of 27 national monuments, Zinke met with Utah’s Republican delegation and the San Juan County Commission — staunch critics of Bears Ears — to discuss next steps. He sat down with members of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, a group of five area tribes that petitioned for monument status, only after they traveled to Washington to demand a meeting, claiming that neither Trump nor anyone on his team had consulted with them.

A week later, Zinke traveled to Utah as part of a monuments “listening tour,” when he spent four days visiting Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante. Monument opponents, including Utah Governor Gary Herbert (a Republican) and members of the San Juan County Commission, joined him on the tour of Bears Ears. Representatives of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition were given a one-hour meeting with the agency chief.

In an op-ed published Sunday in the Salt Lake Tribune, the coalition, one of several groups now suing the administration, called Trump’s rollback of Bears Ears “devastating” and said the administration “failed to meaningfully engage our sovereign nations.”

“The upcoming hearing will uncover the bias, the outsized influence of the mining and drilling industries and the political motivations of the administration that led them to their illegal decision,” the coalition wrote.

Cherry-picked data

In launching its review, the Interior Department claimed that the size of national monuments designated under the Antiquities Act of 1906 “exploded from an average of 422 acres per monument” early on and that “now it’s not uncommon for a monument to be more than a million acres.”

The figure formed the foundation of the administration’s argument that Trump’s predecessors abused the century-old law. But a look at early monument designations upends the agency’s math. In 1908, two years after the Antiquities Act became law, Theodore Roosevelt designated more than 800,000 acres of the Grand Canyon as a national monument. Only a few Obama-era land monuments are larger. Roosevelt also designated the 610,000-acre Mount Olympus National Monument and the 20,629-acre Chaco Canyon National Monument. Republican presidents Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover both designated monuments of over a million acres. Coolidge set aside Alaska’s Glacier Bay in 1925, and Hoover designated California’s Death Valley in 1933.

The Interior Department has never substantiated the 422-acre figure, despite HuffPost’s numerous requests.

Not about extraction, they said

Throughout the process, Zinke maintained that the review and subsequent rollbacks were not aimed at boosting energy and mineral development on once-protected lands.

“I’m a geologist,” Zinke, who is not a geologist, said at a congressional budget hearing last year. “I can assure you that oil and gas in Bears Ears was not part of my decision matrix.”

Media reporting over the last year suggests otherwise. The New York Times obtained emails via a public records request that show potential future oil extraction played a central role in the decision. The Washington Post uncovered a lobbying campaign from uranium company Energy Fuels to shrink Bears Ears. And Roll Call reported this month that Energy Fuels, which owns a uranium mill adjacent to the original Bears Ears boundary, met with a top Interior Department official to discuss Bears Ears even before the agency launched its review.

The Washington Post also reported on agency emails that show Interior Department officials dismissed information about the benefits of establishing protected monuments, including increased tourism and archeological discoveries, instead choosing to play up the value of energy development, logging, and ranching.

A man holds a sign in protest, during Ryan Zinke’s visit to Utah in 2017. George Frey / Getty Images

Nothing to learn from the public

Early in the review process, Interior announced a comment period to give the public a chance to weigh in. It was a move that Zinke said “finally gives a voice to local communities and states” that the Trump administration claimed previous administrations had ignored.

That invitation appears to have mostly been for show. As HuffPost first reported, the agency conducted its review of Bears Ears assuming it had nothing to learn from the public.

“Essentially, barring a surprise, there is no new information that’s going to be submitted,” Randal Bowman, an agency official who played a key role in the review, told colleagues during a May 2017 webinar to train a dozen agency staffers on how to read and catalog public comments. And in a May 2017 email exchange with Downey Magallanes, a former top aide of Zinke’s who played a key role in the review, Bowman said he expected the comments to be “99-1 against any changes.”

The support for keeping monuments intact was indeed overwhelming. An analysis by the Colorado-based Center for Western Priorities found that 99 percent of the more than 685,000 public comments submitted during a 15-day comment period voiced support for Bears Ears.

In a report summary made public in August 2017, Zinke acknowledged that the vast majority of the 2.8 million public comments the department received as part of its sweeping review favored maintaining national monuments, which he chalked up to “a well-orchestrated national campaign organized by multiple organizations.”

He didn’t appear to consider that the comments were the honest opinions of individual Americans.