This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

While there are a lot of alarm bells sounding over how climate change will affect marine ecosystems and the world’s seafood supply in the future, there’s been much less attention paid to the effects it’s already had on them. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates that more than 90 percent of the earth’s warming over the past 50 years has occurred in the ocean. Now, a new, first-of-its-kind study reveals that ocean warming has significantly affected fisheries worldwide, and it’s done more harm than good.

“Everyone wants to know what the future of our marine resources are — the problem is that getting even basic information is hard,” says Daniele Bianchi, an assistant professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Ocean Sciences at the University of California-Los Angeles. It’s a great starting point, he says, “that they can prove there is this influence, and to do that they had to do a lot of work, not just in this paper, but really collecting all the data.”

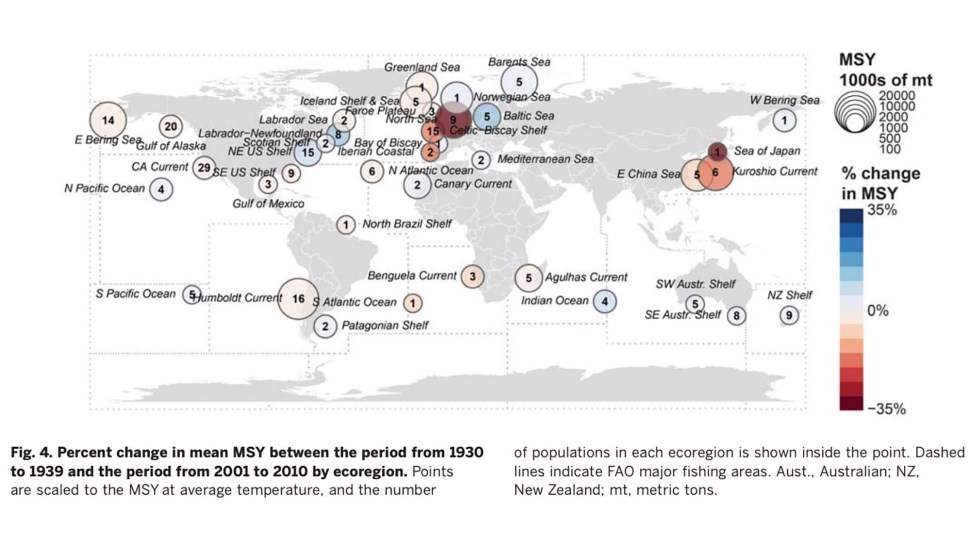

Published Thursday in Science, the study used temperature records and maximum sustainable yield data — a metric showing the most that a resource can be exploited without depleting it — from 1930 to 2010 to determine warming impacts on 235 fish and invertebrate populations around the world. (That sample included 124 species in 38 eco-regions, or about a third of the reported global catch.)

“Most people have been looking at forecasting what the anticipated impacts of climate change are going to be on the future of fisheries, but no one has actually looked at what the impact of climate change has already been,” says Chris Free, the study’s lead author and a researcher at the University of California-Santa Barbara. “It helps us figure out some of the factors that make populations more vulnerable to anticipated climate change.” It also highlights just how significantly future warming could affect the studied populations, since the already-observed changes resulted from about a half-degree Celsius in ocean warming. Projections for the future expect more than three times that increase.

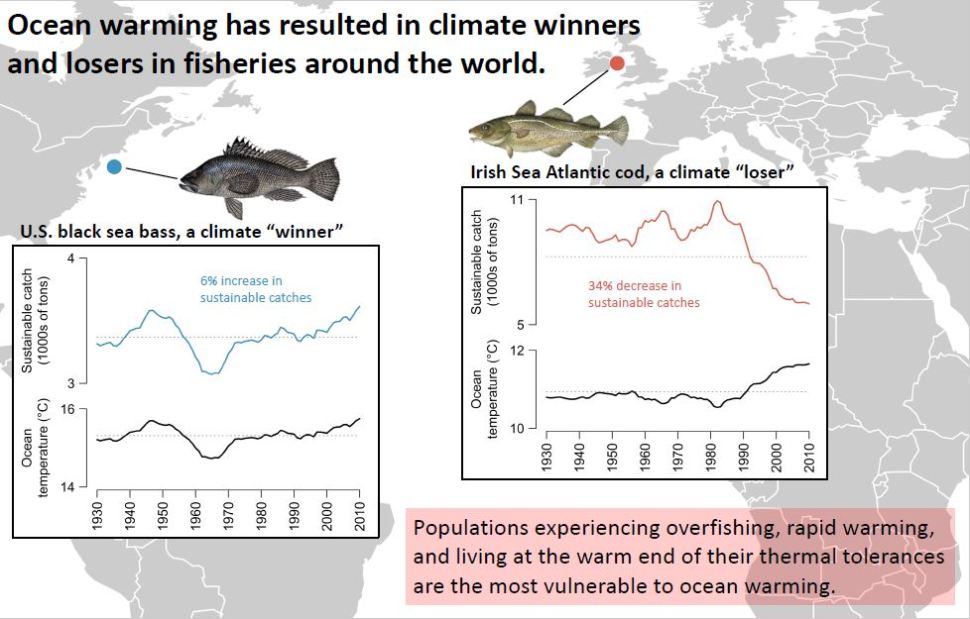

Free and his peers from Rutgers University, the University of Washington, and NOAA found that overall, global sustainable fish and shellfish yields decreased by about 4 percent, with some species, like the Atlantic cod in the Irish Sea, faring worse than others. While 4 percent might not seem huge, it’s still a marked drop, and beyond that, the regional differences are especially striking. Alarmingly, yield losses reached almost 35 percent in some eco-regions.

Courtesy Chris Free

The global decrease “is fairly significant for the past 80 years,” Bianchi says. “Populations of fish that are negatively affected declined quite a lot, and I’m sure the people that rely on these resources might find these results quite worrisome, even more than someone taking the global perspective.”

The biggest losses occurred in the Sea of Japan and the North Sea, where the maximum sustainable yields dropped by over 34 percent. The East China Sea (8.3), Celtic-Biscay Shelf (15.2), Iberian Coast (19.2), South Atlantic Ocean (5.3), and Southeast U.S. Continental Shelf (5) also saw significant dips.

“To see these massive losses in the North Sea, which supports really important commercial fisheries, and also in the East Asian ecosystems that are home to some of the fastest-growing human populations and populations that depend on seafood is really concerning,” Free says.

Beyond the environmental impact, as fisheries change, many worry about the threat to global economics and nutrition. An estimated 3 billion people rely on seafood as their primary source of protein, and global marine fisheries bring in about $100 billion in revenue a year; more than 10 percent of the world’s population depends on them for their livelihood. Moreover, seafood is a major global trade commodity, so the big declines above Northern Europe or in the Sea of Japan, for example, could create ripple effects in other areas as well. “The losses in those ecosystems aren’t just about those countries, but also about the countries they export seafood to,” Free notes. Take the United States, for example, which imported 6 billion pounds of seafood in 2017, more than in any previous year. These imports accounted for more than 90 percent of the seafood Americans consumed. Notably, the data shows an increasing reliance on imports from places like Norway and China.

All that said, there is something of a silver lining, at least in some regions. The study shows that fish in some areas, like the black sea bass off the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf, have actually benefited from ocean warming. But even the good news comes with an asterisk: Many more of the populations studied had a negative versus positive reaction to the warming. And even for the species currently thriving in warmer waters, as the warming increases—as it’s expected to—these benefits could run out when species reach their temperature threshold. “It can’t be good forever,” Free says. “These populations that have been winning aren’t going to be climate winners forever.” Moreover, a number of other climate-fueled factors not included in this research, like ocean acidification and rising seas, have been wreaking more and more havoc on marine ecosystems, so the warming only reveals one piece of the puzzle.

Adding to the risks posed by a changing climate is the problem of overfishing, a persistent and increasing issue plaguing global fisheries, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, which found last year that a third of the world’s oceans are overfished, while fish consumption is at a record high. Significantly, the study reveals an important relationship between environmental change and overfishing (the act of fishing a species so much it cannot replenish itself): The researchers found that the populations that experienced heavy and prolonged overfishing were more vulnerable to the impacts of ocean warming, meaning overfishing could make species less resilient to climate change in the future, and climate change could in turn make it harder to rebuild overfished populations.

“A lot of what happens to fisheries depends on how well they are managed. The impact might be very different if the fishery is currently well-managed or if it’s going to be well-managed into the future,” Bianchi says. “That probably is even more important than climate change.”

With all the moving variables from human interference to complex ecosystem interactions, predicting global warming’s effect on the world’s fisheries is a particularly complicated task. Scientists have gathered huge amounts of data on weather patterns and marine processes via satellites and weather stations, and so have come to understand global warming’s print on the atmosphere and ocean fairly well. But these tools aren’t as helpful when it comes to monitoring ocean-dwellers. Satellites cannot track what’s going on underwater, and a lot of coordinated on-the-ground time and energy is needed to monitor the changing patterns of constantly moving sea critters, Bianchi notes. This makes forecasting the future extremely difficult. So Free’s backward-looking research also has implications for predicting the future.

“The models that we use are as good as the data that we have to constrain them,” Bianchi says. “That’s why I’m excited about these types of papers, because they take all these observations that we trust and that we understand and start extracting the signature of warming.”