Q. Dear Umbra,

I was recently the target of a road rage incident where another driver threw a rock at my passenger side window after I didn’t turn fast enough for him on a red light. Luckily, I wasn’t hurt, but it got me thinking: People don’t seem to freak out at others like that on public transit. What is it about driving makes some people so angry?

— Reckless Anger Gets Everything Ruined

A. Dear RAGER,

Oof! I can’t even imagine what I would have done in your situation — you must have the patience of a saint to not have rammed that guy off the road. Just reading about this scenario, I feel a small storm of violent rage brewing somewhere around my esophagus. I am kind of an angry person, though. It’s definitely not my finest feature, but it is what it is. And for that reason, it might be a good thing that I’m not driving much anymore.

According to a study by Jerry Deffenbacher, a professor of psychology at Colorado State University, road rage isn’t necessarily a syndrome of its own — it tends to crop up in people already prone to anger (like myself and our new shared enemy, Rock Boy). In other words, driving doesn’t create monsters; like whiskey or Monopoly, it simply brings out the monstrous traits individuals already have.

Why is driving such an anger amplifier? Perhaps it’s because cars are marketed with the promise of speed, convenience and Kerouac-like independence, especially in the United States, where having one opens all kinds of social doors. But that fantasy comes at a price: the average cost of car ownership per year in the U.S. is about $8,500, and that’s assuming you don’t have to deal with psychos throwing shit at your passenger window. So because you’re paying all this money to supposedly have complete control of your own mobility, it can be infuriating to end up stuck at a standstill on a freeway that has turned into a parking lot during rush hour.

This is not, of course, a valid excuse to throw a rock at another human being. Or force someone onto the roof of your car and then drive it down the highway, or smash another person’s truck with a golf club.

If you think things are bad now, consider that 20 years ago, “road rage” was considered an epidemic, as documented, however skeptically, in this 1998 Atlantic article. Arnold Nerenberg, a California-based psychologist who advertised himself back then as “America’s Road Rage Therapist,” claimed that 53 percent of Americans had a “road rage disorder.” (Nerenberg was later convicted of worker’s compensation fraud, but that’s a whole separate journey!)

Nerenberg’s credibility aside, it’s easy to deduce a reason why road rage became such a seemingly sudden phenomenon.

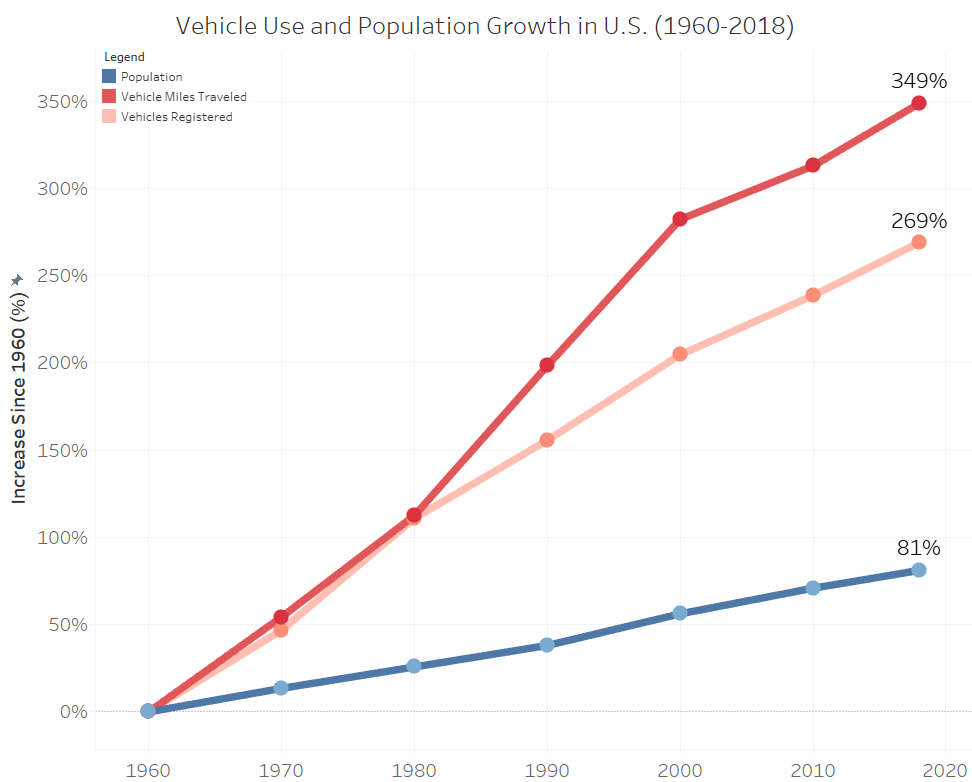

Éamon Finneran / Grist

In the late ’90s, U.S. car ownership had long been on a wild, upwards trajectory. In each decade between 1960 and 2000, car ownership and miles driven grew at a faster rate than the population. In other words, every generation saw more cars on the road than the one before, with trips becoming longer or more frequent or both. Those factors contributed to unprecedented levels of congestion at the time (although not as nightmarish as what we have today). And as Deffenbacher wrote: More traffic equals more traffic-related situations in which rage-inclined people who might otherwise be just fine (DON’T judge us) have the means, motive, and opportunity to truly and spectacularly lose it.

So your new rock-wielding enemy — let’s call him Travis, because in my mind, that’s 100 percent his name — might just be a decent but anger-prone person who had a really, really bad day. There’s not a lot we can do about that, other than track him down and get him court-mandated therapy, but that seems a little extreme. What we can do … is prevent future Travis the Terror moments by putting a higher price on driving. Bear with me; I’ll explain.

Donald Shoup, an economist at UCLA, has studied the phenomenon of parking rage (yes, there are apparently subcategories for road rage) for more than a decade. Humans do psychotic things while vying for parking spots — including murder, in extreme cases. Part of the issue, Shoup points out, is that parking spots are free or very cheap relative to their land value, particularly in cities with high costs of living. That means there’s an outsized amount of competition for those spots, leading people to exhibit some truly crazed behavior. Furthermore, because parking has been free for so long, people think of it as something they’re entitled to rather than something they have to pay for, like food or rent.

“The parking rage occurs when there’s too many people wanting too few parking spaces, and I suppose the road rage must be more common in congested traffic,” he said. “I’m not a psychologist, but people get a sort of territorial feeling: You have a right to this territory, and you feel somebody is intruding on your territorial rights.”

I asked Shoup if he thought his theory on parking could carry over to driving in general. With the exception of tolled highways, roads are free to use and always have been, so most drivers see the road as an entitlement rather than an amenity.

“I bet that putting pricing on roads would lead to less road rage,” he said. “It’s certainly logical.”

We may not have to wait long to test this theory. Some cities like New York, Stockholm, and London have implemented congestion pricing policies, which mean drivers are charged a fee to drive on certain busy city streets at peak hours. (If you want to learn more about it, we’ve covered it here and here on Grist.) The goal of congestion pricing is to reduce traffic in the busiest areas at the busiest times, but they also have the result of cutting back CO2 emissions. And it’s possible it could also lead to a change in the way people think (and rage) about the road.

As for public transit and its relative lack of explosive conflict (I say “relative” because, well, have you ever been on the MTA?): When we use public transit, we accept that we are sharing a space and an amenity with others. We’ve all paid a small price for the privilege to do so, and we’ve entered into a kind of tacit social agreement that we’re probably not going to murder anyone over a bus seat. Even though roads are also shared, public space, cities don’t price them that way. Ergo, territorial rage ensues as everyone believes that they have the supreme right to travel quickly, easily, and independently across town.

So to sum up, RAGER, I still think Road Warrior Travis is kind of an asshole, but he’s not acting in a vacuum. Everyone needs to be reminded that roads are a shared resource and no one owns them, and often the most effective way to do that is by making people literally pay for the privilege! So after you slash his tires — just kidding! BAD Umbra — head on over to your local city council meeting and let officials know that truly shared, mutually respected roads are … well, priceless.

Furiously,

Umbra