It’s Friday, December 14, and negotiators at the U.N. climate talks finally acknowledged climate refugees.

![]()

Not a lot has been accomplished so far at this year’s U.N. climate talks in Poland. The summit, which wrapped up today, started off under a cloud of coal dust (literally). Some countries (cough cough, U.S.A.) even thought the talks would be a great opportunity to discuss fossil fuels. But one moment stands out: negotiators finally agreed to consider instating some policies on climate migration.

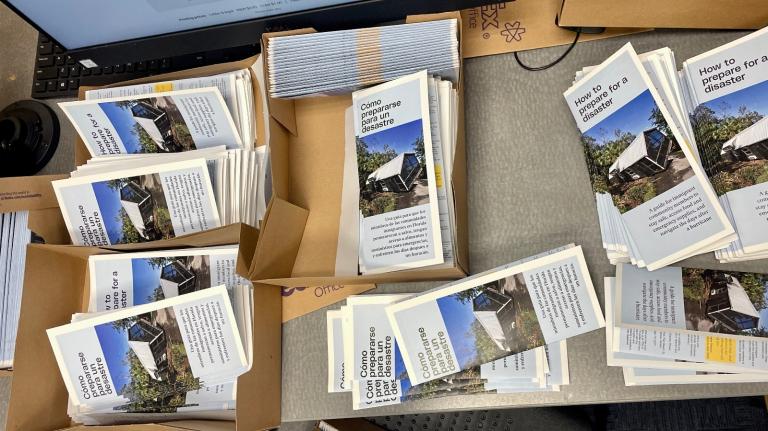

Climate migration is something developing countries have been sounding the alarm on for a while. The U.N. estimates 140 million people could be displaced by desertification alone by 2045. On Saturday, they approved a new set of guidelines that could help people who have been driven from their homes by climate-related disasters. That means that, at least for the next five years, climate refugees will be part of the global conversation around climate change.

So the problem has been recognized — a good step forward. But here’s the glaring omission: The new guidelines don’t come with any money attached, which is a necessary piece of solving this climate migrant puzzle.

The Smog

Need-to-know basis

Despite delays (thanks again, United States), negotiators at the U.N. climate conference in Poland are closer to an agreement on how to implement the Paris Climate Agreement. The stakes are high for climate-vulnerable island countries, like the low-lying Maldives. “We are not prepared to die,” said Mohamed Nasheed, the Maldives’ leader.

![]()

Back in 2009, the Environmental Protection Agency determined that six greenhouse gases “threaten the public health and welfare of future generations.” This “endangerment finding” is the legal underpinning for Obama-era climate policies to curb emissions. Now (as the Team Trump attempts to weaken the Clean Air Act), a study in the journal Science says those gases pose an even bigger threat than previously thought.

![]()

While the Trump administration may not care about greenhouse gases, it is tracking peaceful climate protesters. A group protesting an oil refinery on the shores of Lake Michigan has found themselves mentioned in a federal surveillance report, according to documents obtained by the Guardian through the Freedom of Information Act. The FBI is technically prohibited from investigating groups or individuals solely based on their political beliefs.