It’s Wednesday, September 1, and weather conditions have turned California into a powder keg.

Good morning, Zoya here. There are 83 large fires burning across the U.S. right now. More than a dozen of those are in California, where hot and windy conditions over the weekend helped fuel blazes that are still nowhere near fully contained. The U.S. Forest Service is taking the extraordinary step of closing all national forests in the state due to the threat of wildfire.

Right now, all eyes are on the Caldor Fire, which broke out in El Dorado County two weeks ago and has burned some 200,000 acres. On Tuesday, the fire descended into the Lake Tahoe Basin, home to tens of thousands of people and the largest alpine lake in North America. Caldor, which is currently only 16-percent contained, has prompted local officials to issue mandatory evacuations for all of South Lake Tahoe and other affected areas.

Elsewhere, a new fire broke out roughly 500 miles south in San Diego County on Saturday, burning nearly 1,500 acres in less than a day. The Chaparral Fire was 50 percent contained on Tuesday evening. The Dixie Fire, which started on July 13 just east of Paradise, is the second-largest wildfire in California state history and is still burning in five counties. It’s less than 50-percent contained. The Boundary Fire in Idaho, which was first detected on August 10, flared up again and has burned close to 5,000 acres.

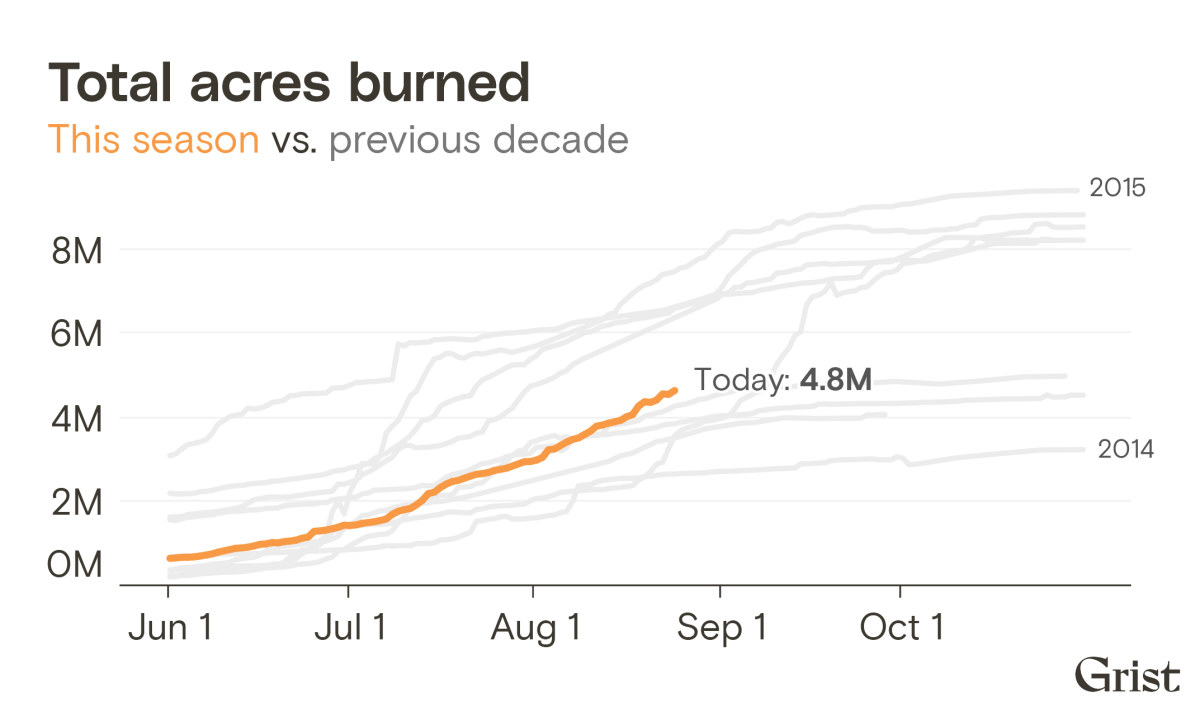

Nearly 6 million acres and 4,000 structures have burned in wildfires so far this year, and the U.S. has spent more than $3 billion on wildfire suppression. And per the National Interagency Fire Center’s request, some 200 U.S. Army soldiers will receive training to assist the more than 27,000 wildland firefighters and support personnel battling blazes in the West.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

As fire outpaces people, one town actually acted.

Hello, Nathanael here!

Earlier this year, the town of Grizzly Flats, California, was set to remove brush and small trees from it’s forested outskirts — a project funded by the Sierra Nevada Conservancy and intended to help protect a community recognized as “exceptionally isolated and vulnerable to catastrophic wildfire.”

But before the work could begin, the Caldor Fire wiped the town off the map.

The incident is far from the only example of fires moving faster than our ability to adapt. In many places, it feels as if the wheels of politics grind slow. The community discussions over what should be done to prepare for wildfire can feel intractable. But when I asked around to learn if there was an example of a place breaking through the deadlock and taking dramatic measures, I kept hearing about Ashland, Oregon.

Back in the ‘90s, the community couldn’t have been more polarized. When the Forest Service proposed removing trees and cutting fire breaks to reduce the city’s fire risk, environmentalists in ski masks showed up to warn that there would be dire consequences if a single tree fell. But over the years, the town, environmentalists, and the Forest Service have achieved near-consensus on what needs to be done — and gotten down to work.

When logging trucks full of thinned out trees huffed through downtown Ashland in 2004, liberal locals waved “with all five fingers this time,” one Forest Service lifer told me. Crews removed smaller trees and brush, allowing the town to begin a regime of controlled burning year after year — efforts that have reduced the potential for a fire to rise into Ashland’s tree canopy by 70 percent.

A controlled burn near Ashland, Oregon. Photo courtesy of The Nature Conservancy

The details of how the groups in Ashland made their way from white-hot animosity to mutual respect and trust — including a tradition-bucking female ranger, a man named Bobcat, and environmentalists with chainsaws — are featured in this week’s Grist cover story.

As a climate journalist, I feel like there’s an unending stream of warnings and disasters to cover, and precious few solutions. That’s upside down: I don’t need to be convinced there’s a problem, I just need the tools to solve it. And Ashland’s story offers some of those tools.