Happy September 15, Nathanael here.

President Joe Biden was in Idaho and California on Monday to tour communities ravaged by this season’s wildfires. “We can’t ignore the reality that these wildfires are being supercharged by climate change,” he said.

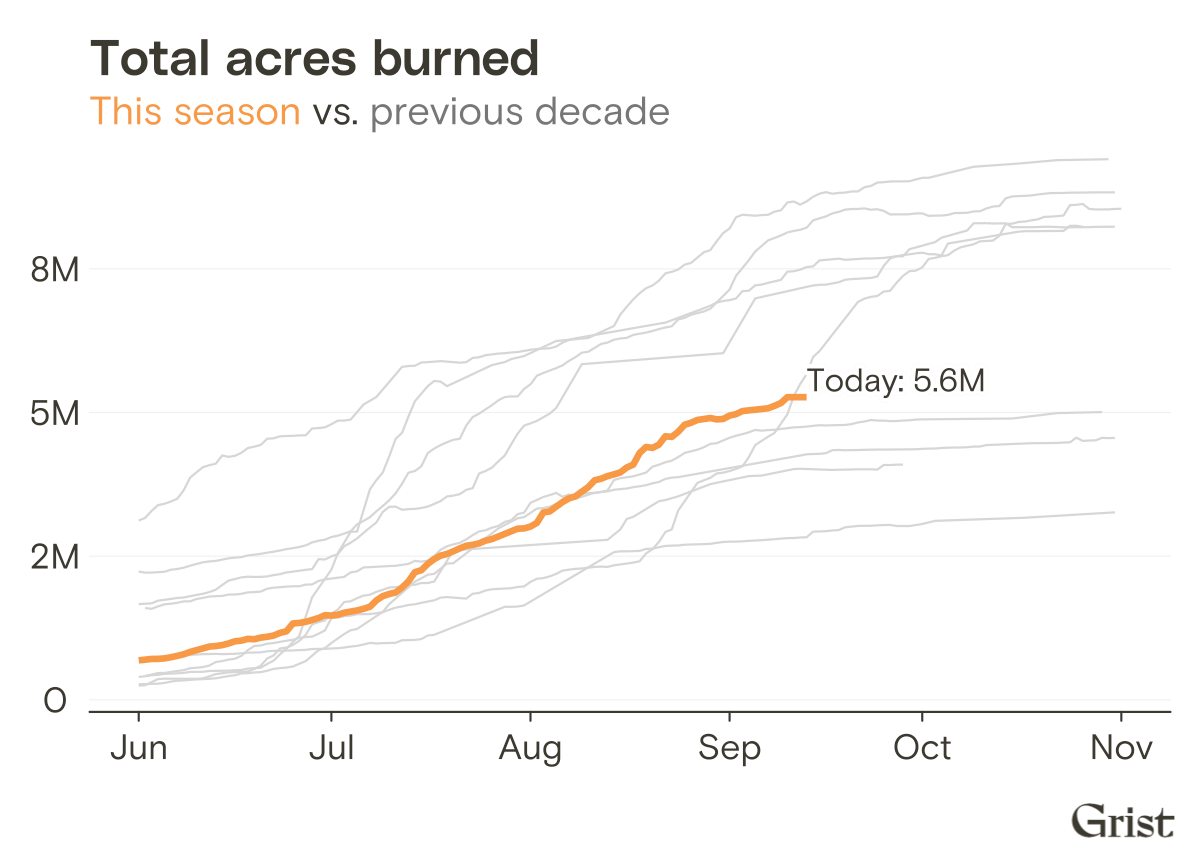

Some 5.6 million acres have burned so far this year. The big fires in California, which have dominated the news, finally appear to be slowing down because they are simply running out of room. The eastern arm of the Dixie Fire is sandwiched between the Beckworth Complex (which burned earlier this year) and 2019’s Walker Fire, where there’s a lot less fuel to burn.

That is allowing crews to focus efforts elsewhere. After weeks of fire departments sending every available worker to Northern California, you can now see fire engines heading down from the mountains, back to Los Angeles and the Bay Area. Rain has also helped to cool the blazes. It arrived with lightning, however, which set new fires in the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

Cases of a mysterious disease are on the rise. What role is climate change — and wildfire, specifically — playing in the spike?

Hello! It’s Zoya.

This summer, thick plumes of smoke from wildfires burning in the western U.S. drifted across the country, prompting local officials as far east as Portland, Maine, to issue air-quality warnings. Studies have shown that these kinds of smoky days have deleterious effects on the human respiratory system.

Wildfire smoke carries particulate matter that can bury itself deep in the lungs. Those tiny particles can aggravate heart and lung diseases and even lead to premature death. But scientists still know remarkably little about what other harmful elements wildfire smoke might carry.

“The potential for human pathogens to be spread in wildfire smoke has been ignored by those working on the health impacts of wildfire smoke,” Jason Smith, a professor of forest pathology at the University of Florida, told me recently. I had called him up to talk about a disease called Valley fever, which is caused by a fungus that lives in the soil of the desert Southwest and western U.S.

Cases of the disease, which develops in people who breathe in the fungus spores, are on the rise: The number of people diagnosed has increased by 32 percent nationwide in recent years. One study determined that cases in California rose 800 percent between 2000 and 2018. And for the roughly 40 percent of people who develop symptoms, the infection can be quite serious.

That’s what happened to Jesse Merrick, a sportscaster and former football player. Merrick thinks he got Valley fever after helping his mom clear out the wreckage of his childhood home after it burned down in 2017’s Thomas Fire.

Smoke and dust blow off the burned remnants of Jesse Merrick’s family’s home after the 2017 Thomas Fire. Courtesy of Jesse Merrick

A few weeks after he returned home to Alabama, Jesse started coughing and running a low-grade fever. A rash appeared on his upper torso. “I remember being miserable,” he said. “I wasn’t sleeping.” Once the rash started to move up his neck, about four days after he first started feeling sick, Jesse knew he had to get to an urgent-care clinic. It would be three more agonizing weeks before an infectious disease specialist finally diagnosed him with Valley fever, which is caused by the fungus Coccidioides.

Scientists aren’t exactly sure what environmental factors drive Cocci transmission. A pattern of intense rainfall and severe drought, some researchers speculate, could be behind the recent explosion of cases. But experts are still puzzling out what, if any, connection wildfires have to Valley fever.

Smith, the professor from the University of Florida, is working on a study that will, in part, determine whether Coccidioides can travel in wildfire smoke. His research is still in its early stages, but previous studies he’s worked on have demonstrated that fungal spores can indeed travel far distances on wind and by clinging to the particles in wildfire smoke.

“There’s just no reason why Coccidioides would be immune from that,” he said.

In this week’s Grist cover story, I dive deep into Valley fever and the reasons why the disease is on the rise in many western states (spoiler alert: climate change plays a role). To read the piece, click here.