It’s Wednesday, September 8, and all the biggest fires are burning in California

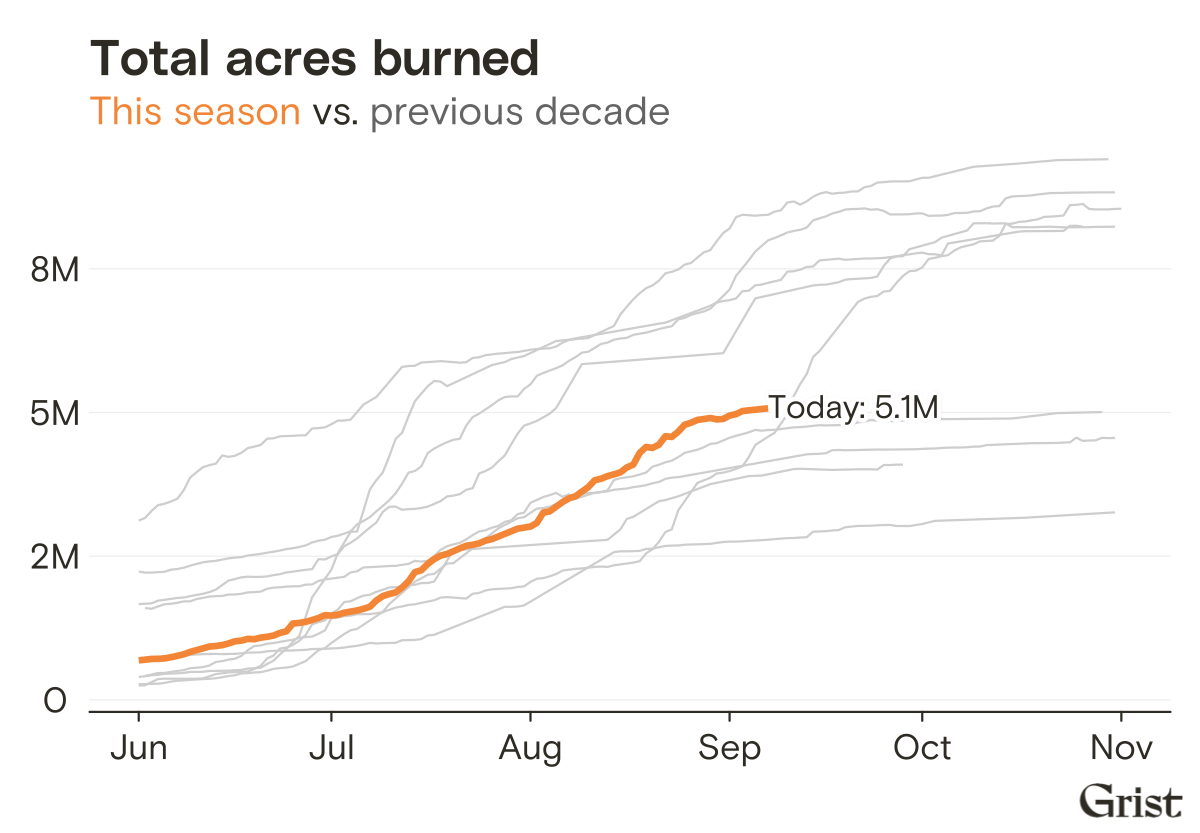

Good morning, Nate here. There are 81 large fires burning in 11 U.S. states right now. Some 5.1 million acres have burned so far this year, and wildfire suppression costs have reached $3.3 billion. The biggest of the lot, the Dixie Fire, is already one of the largest wildfires in California history, topped only by last year’s August Complex, which burned more than a million acres. But the Dixie Fire is closing in on that record. Some other regions of the country experienced their biggest burns long ago: The Miramichi Fire of 1825 that cut across Maine and into Canada, the Great Michigan Fire of 1871, and The Big Burn of 1910 in the Rocky Mountains. Each consumed millions of acres. Now it’s California’s turn: Nine of the 10 biggest wildfires in the state’s history have occurred in the last decade — six of those since the start of last year.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

In the drought-stricken West, fires further threaten water supplies

Zoya here. Some evacuation orders were downgraded to warnings this week for parts of Lake Tahoe as firefighters managed to contain 49 percent of the Caldor Fire, a blaze that threatened to wipe out towns surrounding North America’s largest alpine lake. But even though Caldor has so far been kept away from South Lake Tahoe, ash from the blaze has reached Lake Tahoe, turning its famed crystal blue waters cloudy. Scientists aren’t yet sure whether the murkiness will encourage more algae blooms or cause other damage, but they know from past experience that wildfire ash, soot, and smoke can have lasting effects on water quality and, by association, public health.

In 2018, a faulty transmission line on Camp Creek Road in Northern California’s Butte County ignited the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in the state’s history. The Camp Fire left behind razed towns and charred landscapes and also sent a cocktail of volatile compounds into the town of Paradise’s 172-mile network of underground water pipes. In order to rid its water supply of fire-borne contaminants such as benzene, toluene, and xylene — chemicals linked to adverse health effects in humans — Paradise had to spend millions clearing and replacing its pipes.

A smoky sunset is seen over Lake Tahoe on September 6. Jane Tyska / Digital First Media / East Bay Times via Getty Images

A recent article by a team of researchers from the American Geophysical Union, or AGU, illuminates the breadth of the wildfire-related water quality crisis across the country. When a fire burns through an area, it leaves a layer of loose ash on the ground. The lightweight ash contains tiny particles called dissolved organic matter, which can linger in burned landscapes for years, even decades. When rains eventually come, as they will later this year in California and other states badly affected by wildfire, that organic matter, called PyDOM, can leach into nearby water sources, creating a host of problems that are expensive and difficult to address.

The AGU researchers clocked changes in water coloration and taste following nine major wildfires in California, South Carolina, and Colorado between 2002 and 2020. They noted that PyDOM served as a kind of petri dish for microbial growth in water in burned watersheds. This required cities and towns to pour more treatment chemicals into their water, like chlorine and ferric iron. But the disinfection process creates its own set of problems: Disinfectants can form byproducts with PyDOM, and some of those can be toxic. Chloramination, for example, a process used to disinfect drinking water, can produce N-nitrosodimethylamine — a chemical compound that is a known carcinogen in laboratory animals — when it’s introduced into water that contains PyDOM.

Wildfire ash runoff doesn’t just make water treatment more complicated and pricey, it may also create dangerous knock-on effects. Burned biomass, fire retardant, and suppression chemicals such as inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus can choke aquatic wildlife where they enter rivers and streams and spark algal blooms. Some of those blooms contain algae that create naturally-occurring brain and liver toxins and complicate water treatment.

All of these fire-related side effects on the country’s water supply pose problems long after the flames are gone. And, as climate change fuels bigger and more intense fires, the threat to water quality is sure to become an increasingly urgent concern. “As wildfires burn hotter and consume more fuel in future climates, water quality will progressively degrade,” the researchers said. Water utilities, they noted, need to prepare.