Hello and welcome to late August! Nathanael here.

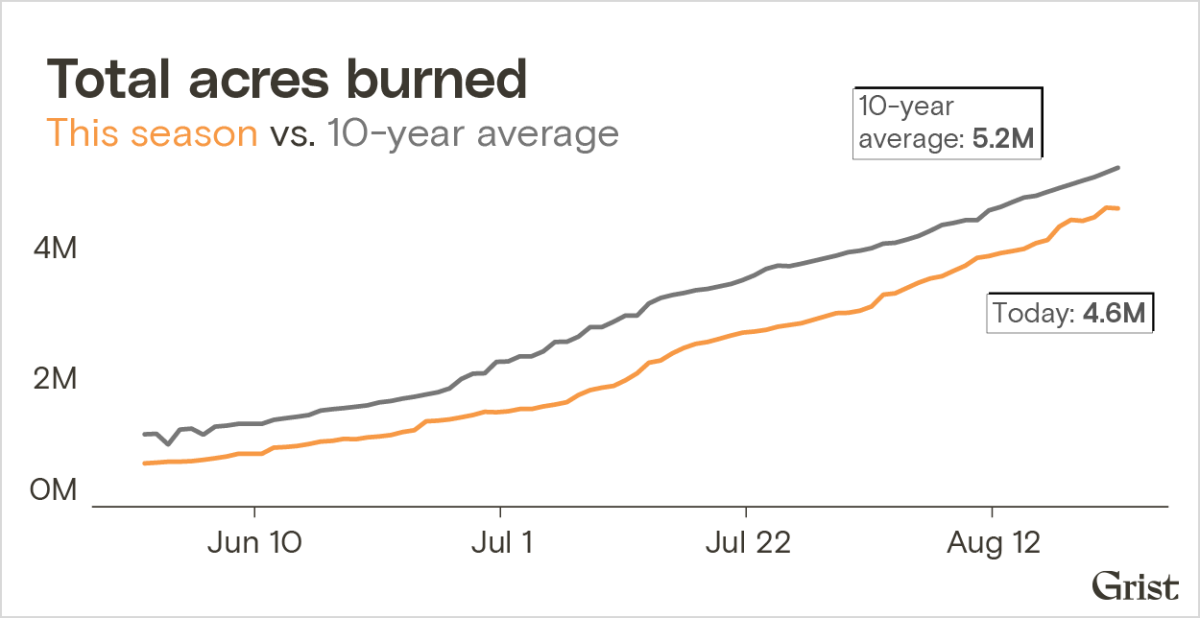

There are 77 large uncontained fires burning across the U.S. this week, down from over 100 last week. Firefighting crews shifted resources to California to attend to four blazes over 100,000 acres. Those include the biggest fire in the country, the 700,000-acre Dixie Fire, and the explosive new blaze, the Caldor Fire, which erupted to 115,000 acres in just 9 days, becoming the latest exhibit of “unprecedented fire behavior” this season. Thousands of people have left their homes under mandatory evacuation orders.

While the biggest blazes char California, many others are crackling in other parts of the country. A string of fires is burning up the Cascade Mountain Range through Oregon and Washington, nearing 650,000 acres in all. Some 800,000 acres are aflame in the Great Basin and Northern Rockies. And it’s not just the West — fires are also burning in Minnesota’s Superior National Forest, shutting down access to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness for the first time in nearly half a century.

How long could this possibly last?

Because I write about climate change and wildfire, and live in California, friends sometimes text or email asking me some variation of the same question: “Is this going to happen every year now?” They are asking about the grubby skies, the life-shortening grit in their sinuses, the cancelled outdoor plans, and the annual dose of fear that fire will consume their family, or their home. They are asking if they should leave California for good.

My answer: It all depends on how we humans react to the crisis we’ve created.

A recent paper projecting wildfire behavior casts a little light on the problem. Researchers were modeling possible futures for 16,000 acres south of Yosemite, on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The study, published in the journal Ecosphere, was especially noteworthy because it didn’t just look at how higher temperatures would affect fire, or how climate change might affect plant growth — but both at the same time: The complex interplay of heat crisping vegetation, drought suppressing growth, and fire consuming fuel.

Basically, the model suggested an intense burst of big fires over the coming decade, and then a regime of smaller, cooler fires.

The catch is that scientists let the fires in their model burn unimpeded, with no suppression, allowing the blaze to remove fuels from the forest. “Once you scale up to entire regions, a lot of the self-limiting effects of wildfires run out after 10 years of regrowth,” said Maureen Kennedy, one of the scientists behind the study, who is based at the University of Washington, Tacoma. “And so if you go back to suppressing fire again, you’re back where you started.”

This particular tract of forest isn’t analogous to the wet forests of the Olympic Peninsula, or the lodgepole pine forests of the Rocky Mountains. But it is a great example of the kind of forests that have recently burned very hot and generated a lot of smoke, like the North Complex Fire near Oroville, and the Creek Fire, which consumed some of the study area.

The question is: Are we willing to let blazes burn unimpeded for a decade if it means a less intense fire future? The scientists’ study area was a largely uninhabited swath of national forest. It’s politically difficult to reduce fire suppression even a little bit (see last week’s newsletter, for instance), because Americans tend to assume that firefighters will save every single home and every single tree they can. Fire officials could ease up on suppression in unpopulated forests, while still fighting fires at the edges of communities, but they are often afraid to do anything but extinguish the flames as soon as possible.

We are in the middle of a new period where it feels like there are bigger and bigger fires every year. It can be frightening. But if humans are willing to allow the fires to clean up the forests, this chapter might be relatively short.

Or as Kennedy said: “What happens next is up to us.”