Hello, it’s Zoya, and today is Wednesday, September 29.

The onset of fall is continuing to aid wildland firefighters in their efforts to contain blazes in the western U.S. But fire season is still far from over, especially in California. The Santa Ana winds, the very dry, flame-fanning gusts that blow into southern California every year usually start in October. The phenomenon, which is now right around the corner, has turned bad fires into catastrophic blazes in the past.

There are 44 large uncontained fires burning in the U.S. at the moment from the west coast to the plains. Idaho has 20 of those fires, the most of any state. In California, more than 2,000 firefighters are working to contain the Windy Fire, which is threatening the Sequoia National Forest and is burning on the Tule River Indian Reservation. In the Central Valley, the Fawn Fire has destroyed 184 homes. A 30-year-old woman who said she was attempting to hike to Canada was arrested on suspicion of starting that fire. She claims she got thirsty on the trek and tried to boil some potentially bear urine-contaminated water she found in a puddle.

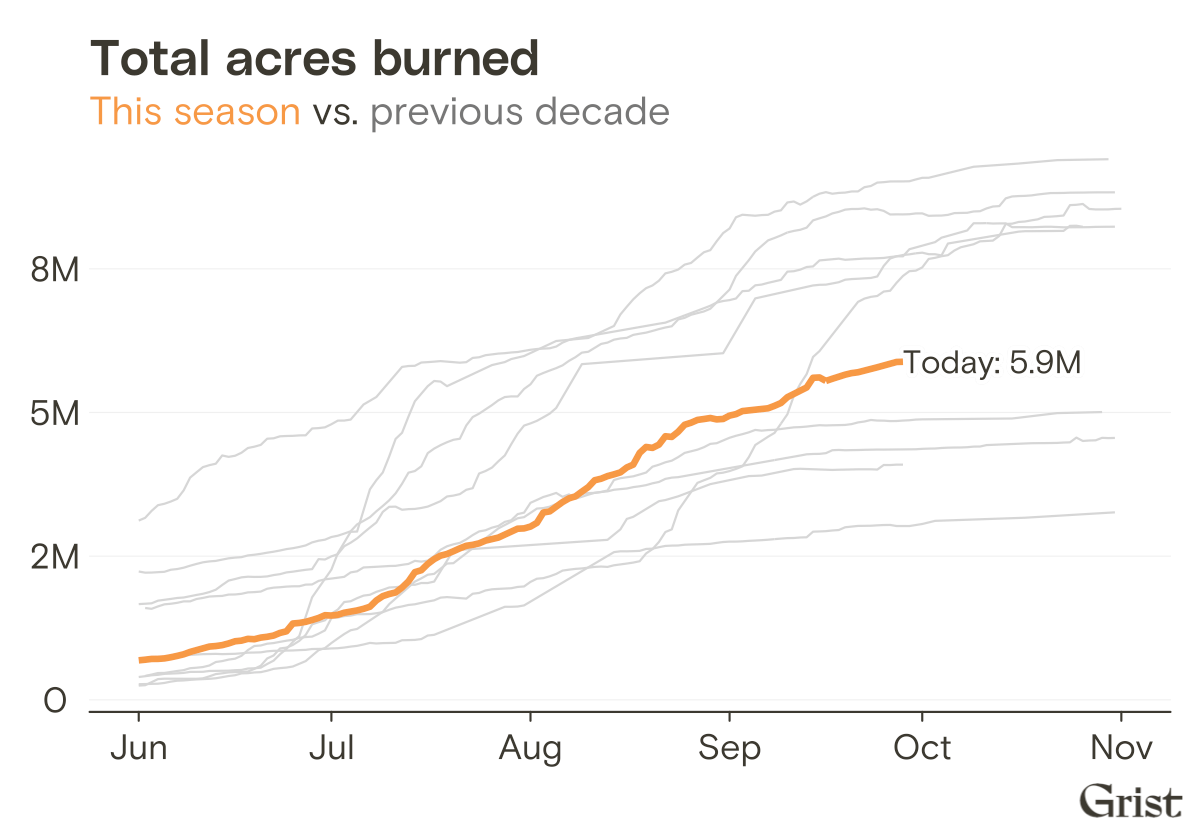

All told, fires this year have burned close to 5.9 million acres, and wildfire suppression costs have now topped $4 billion.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

The problem with focusing on fire size

Hello, Nathanael here. The graphic that we display in every weekly newsletter shows a 2021 fire season that is fairly normal compared to the last 10 years. It does, however, look huge compared to the average fire season in the 1990s or 1980s. We at Grist picked the acres burned statistic as a representation of the severity of this fire season because it was clear, accurate, and available.

But a big area burned isn’t necessarily a sign of doom. When fires kill people and wipe out rare habitats, they are disasters. When they thin forests, cycle nutrients, and foster rare habitats, they are a boon. Scientists studying fires in North American forests have begun asking journalists to be a little more specific in our language when talking about acres burned. In response, journalists are beginning to attach adjectives to the word fire. Yes, some fires are “destructive” or “catastrophic,” but others are “gentle,” “cool,” or “restorative.” As environmental journalist Andy Revkin pointed out, there are many other cases where our cliches tilt us toward thinking of burns as bad. For instance, we don’t always need to fight fires — sometimes we should guide them instead.

In a 2019 paper, University of California, Merced, fire scientist Crystal Kolden found that forest managers were already intentionally using prescribed fire on some 2.5 million acres a year. But 70 percent of that burning is happening in the Southeast, she found, particularly in Florida. (Meanwhile, there’s very little controlled burning happening in the Western forests that need it most.)

The Caldor Fire burns through trees on Mormom Emigrant Trail east of Sly Park, California. AP Photo / Ethan Swope

This may be an unpopular opinion, but even uncontrolled burns can do some good. California’s most severe wildfires this year — the Dixie and Caldor fires — have been both big and destructive for homes and habitat. But we can’t ignore that large swathes of those same fires have done good work for forest health, converting woody debris on the ground to fertilizing ash, killing smaller trees, and opening up glades. Check out the Forest Service’s analysis of soil burn severity from the Caldor Fire: The fire hammered gigantic patches, but it also left 47 percent of the pine-needle filled soil relatively intact.

We humans usually start out with binaries as we come to understand things. Is that unknown sound a threat, or not? Is it good, or bad? As we become acquainted with phenomena, we usually figure out that they are both good and bad. It wasn’t so long ago that people assumed we’d be better off if we rid ourselves of every germ. Now, society has accepted the notion that there are good, bad, and neutral germs, and that we can’t live without them. We’re in the process of figuring this out for fires as well.